JSER Policies

JSER Online

JSER Data

Frequency: quarterly

ISSN: 1409-6099 (Print)

ISSN: 1857-663X (Online)

Authors Info

- Read: 89790

|

ADHD И ОСАМЕНОСТА КАКО ОПШТЕСТВЕНО НЕЗАДОВОЛСТВО ВО ИНКЛУЗИВНИТЕ УЧИЛИШТА ОД ПАРАДИГМА НА ИНДИВИДУАЛЕН КОНТЕКСТ

Факултет за психологија, |

|

ADHD AND LONELINESS SOCIAL DISSATISFACTION

Viviana LANGHER 1,

Faculty of Psychology, |

|

Примено: 09. 09. 2009 |

|

Received: 09. 09. 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

Вовед |

|

Introduction |

|

|

|

|

|

Голем дел од истражувањето покажа дека децата со ADHD во голема мера се соочуваат со тешкотии во односот со своите врсници. Тие покажаа дека имаат повеќе специфични недостатоци во нивната способност да учествуваат, соработуваат и комуницираат со врсниците (1), и дека вештините на општествена комуникација се чини дека е областа со најголем недостаток (2-3). Како последица, општествената неадекватност, вклучувајќи агресија, невнимание, хиперактивност, би воделе до одбивање од врсниците и изолација (пр. 4-13). Децата со ADHD се перцепирани како повознемирувачки и поагресивни од нивните врсници (14), послаби во општествените перформанси, помалку се прифатени и со помалку пријатели; не се омилени кај децата со повисок статус во групата на врсници, наведувајќи на процес на исклученост од попопуларните врсници (15, 16). |

|

A great deal of research reported that children with ADHD widely experience difficulties with their peers. They have been shown to have more specific deficits in their ability to participate, cooperate, and communicate with peers (1), and that social cooperation skills seem to be the largest deficit area (2-3). As a consequence, social inadequacy — involving aggression, inattentiveness, hyperactivity — would lead to rejection by peers and isolation (e.g. 4-13). Children with ADHD are seen by their peers as more disruptive and aggressive (14), found lower on social preference, less well liked and with fewer dyadic friendships; disliked by children of higher status within the peer group, suggesting a process of exclusion by more popular peers (15, 16). |

|

|

|

|

|

Деца со ADHD во училиштата: кршење на правилата |

|

Children with ADHD in school: breaking the rules |

|

Сите училишни системи во западниот свет, без разлика дали се инклузивни или ориентирани кон посебно образование, се засноваат на две имплицитни правила што не може да се кршат. Овие ја карактеризираат афективната симболизација на училишниот контекст (19) што може да се дефинира како емоционални, имплицинтни претставувања споделени од учесниците во контекстот, како што е училишниот контекст во нашиот случај: учителите имаат одговорност и моќ на знаење, додека учениците имаат одговорност и обврска за учење. Кога детето не може да ги постигне целите на учењето кои му се поставени заради некои недостатоци (неспособност, болест, сиромаштија, недостаток на јазични вештини заради тоа што е имигрант итн.), тоа дете често се перцепира како дете кое не може да ги достигне тие цели. Затоа училишниот систем, и инклузивниот и оној ориентиран кон посебно образование, иако со многу различни пристапи, ги обезбедува сите услови кои се потребни да се поддржи тоа дете во постигнувањето на образовните цели. |

|

All school systems in the Western world, whether inclusive or special education-oriented, are based on two implicit rules that cannot be broken. These characterize the affective symbolization of the school context (19) that can be defined as emotional, implicit representations shared by the participants in a context, such as the school context in our case: teachers have the responsibility and the power of knowledge, while the pupils have the responsibility and the duty of learning. When a child cannot achieve the learning aims provided him/her because of some disadvantages (disability, illness, poverty, a lack in linguistic skills due to being an immigrant etc.), that child is often perceived as a child who cannot reach such aims, and the school system, both inclusive-oriented and special education-oriented, though with very different approaches, provides all the conditions necessary to support that child in reaching his/her educational aims. |

|

|

|

|

|

Деца со ADHD и училишната средина |

|

Children with ADHD and educational settings |

|

Споменатите студии, иако во голема мера ги влечат примерите од училиштата, не се однесуваат на училишниот контекст како фактор вреден за истражување во однос на ADHD-синдромот. Како што нагласува Hoza (15) адресирањето на децата со ADHD-проблеми со врсниците од концептуална рамка која се фокусира на едно дете и неговите недостатоци, би водела до потценување на групните процеси во кои проблемите со врсниците се развиваат и според кои тие се засилени. Сепак, образовниот контекст може значително да варира во однос на образовните стратегии за децата со ADHD (посебно или инклузивно образование, во различни средини) и наставните методи (кооперативни и традиционални засновани на предавање). |

|

The mentioned studies, although largely drawing samples from schools, do not refer to the school context as a factor worthy in itself to be investigated in relation with ADHD syndrome. As Hoza (15) underlined, addressing children with ADHD peer problems from a conceptual frame that focuses on the individual child and his/her deficits would lead to the underestimation of the group process in which peer problems develop and by which they are reinforced. Peer relationships, hence peer problems, widely develop in school. Yet, the educational context can considerably vary in terms of educational strategies for children with ADHD (special or inclusive education, with a variety of settings), and teaching methods (cooperative or traditional lecture-based). |

|

|

|

|

|

Инклузивното образование и ADHD-синдромот во Италија |

|

Inclusive education and ADHD syndrome in Italy |

|

Италијанскиот образовен систем е во основа јавен, со над 90% студенти кои посетуваат државни училишта и може да се смета за еден од најинклузивните образовни системи во западниот свет. Всушност, инклузивното образование постои како единствен образовен систем во последните 30 години. Врз основа на убедувањето дека децата со посебни потреби подобро ќе ги постигнат своите академски и општествени цели ако бидат сместени во нормална (пр.: богата, разновидна, реална) средина, и дека соработката со хендикепираните деца е општествена вредност што школите имаат одговорност да ги образуваат децата, во 1977 (27), посебните класови беа засекогаш укинати. Во 1992, изминатите 15 години на искуство со целосна инклузија беше преточено во општ закон (28) што ја организира школската инклузија заедно со социјалните и здравствените служби во однос на проблемот со хендикепираноста, и беше признаен од Европската агенција за развој и образование за посебни потреби како напреден и добро дизајниран (29). Законот пропишува дека се дозволува само две хендикепирани деца во клас, и дека класовите каде има хендикепирани деца не може да бројат повеќе од 20 деца. Исто така, за да се постави индивидуален образовен план за хендикепираното дете од страна на редовните наставници, наставниците кои помагаат и здравствените професионалци, официјална дијагноза може да се направи само во рамките на мрежата на Националната здравствена служба. |

|

The Italian educational system is basically public, with over 90% of students attending state schools and can be considered one of the most inclusive education-oriented systems in the Western world. In fact, inclusive education has been existing as the only educational system for the past thirty years. On the basis of the conviction that children with special needs would better achieve their academic and socialization goals if placed in a normal (i.e. rich, various, real) relational environment, and that cooperation with disadvantaged children is a social value that the school has the duty to teach to children, in 1977 (27), special classes were once and for all abolished. In 1992, the past fifteen years of experience in full inclusion was articulated into a general law (28) that organized school inclusion in connection with social and health services regarding the disability problem, being acknowledged by the European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education as advanced and well-designed (29). The law establishes that no more than two disabled children per class are allowed, and that classes in which a disabled child is included cannot exceed the number of twenty students. Also, in order to set up the Individualized Educational Plan for the disabled child made by regular teachers, support teachers and health professionals, an official diagnosis can be made only within the network of the National Health Service. |

|

|

|

|

|

Посебноста на децата со ADHD споредено со децата со други посебни потреби во инклузивниот образовен систем |

|

The peculiarity of children with ADHD compared to children with other special needs in the inclusive educational system |

|

Системот како италијанскиот, на истражувачите им нуди доста интересна образовна средина за истражување, бидејќи целосната инклузија не е само опција или ограничен експеримент. Напротив, бидејќи е стандардизирана со закон, таа е тестирана со текот на времето и стана дел од културниот систем, правејќи многу фактори доста хомогени, како општественото претставување на наставниците, родителите, соучениците за хендикепираните студенти/врсници, состав на класот и дијагностичката процедура. Во еден таков систем, сите деца независно од видот и сериозноста на нивните посебни потреби, посетуваат исклучиво нормални класови. Наставниците (редовните и за посебна поддршка) ќе бидат обучени за справување со посебните потреби и студентите ќе бидат запознаени уште од почетокот на академскиот живот за посебните потреби на различните соученици, меѓу кои ADHD е само една. Неколку италијански студии покажаа значителен позитивен однос на врсниците кон нивните соученици со посебни потреби, што го намалува ризикот од изолација и проблеми со врсниците за овие деца (пр. 31-35). Ова се чини не е посебен италијански резултат. На пример, Wiener (36), истражувајќи го емоционалното функционирање на децата со проблеми во учење во неколку образовни средини, дојде до заклучок дека иако сите деца со проблеми во учење покажаа потешкотии и проблеми во емоционалното функционирање, сепак, оние во поинклузивни средини секогаш повеќе напредуваа. |

|

A system like the Italian one offers researchers quite an interesting educational setting of investigation, as full inclusion is not simply an option or a limited experiment. On the contrary, since standardized by the law, it has been tested in time and has become part of the cultural system, making many factors, such as teachers’, |

|

|

|

|

|

Метод |

|

Method |

|

|

|

|

|

Учесници |

|

Participants |

|

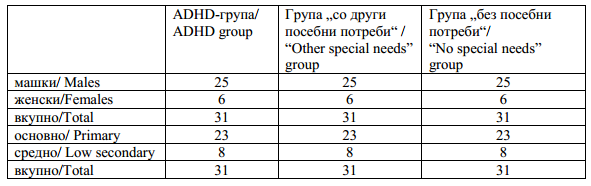

Деца со ADHD беа селектирани од 200 класови од основните и средните училишта (возраст од 6 до 13 години) во провинцијалните области на Рим и Исернија, контактирани благодарение на соработката на канцелариите за образование од провинциите. Во овие 200 класови, 40 деца беа дијагностицирани дека имаат ADHD (се состои од распространетост од околу 0.8% во нашата студија). 9 од овие деца не учествуваа во студијата, резултирајќи со конечен примерок од 31 дете. Сите тие официјално се дијагностицирани од локалното здравствено одделение и сите имаа хиперактивна форма. Бројот на децата под медицински третман е непознат, бидејќи овие податоци се приватни. Сепак, многу е веројатно дека овој број е занемарлив имајќи го предвид малиот број на италијански деца кои се приклучија на ADHD-регистарот за медицински третман. |

|

Children with ADHD were selected from 200 classes from primary and lower secondary schools (ages 6-13 years) in the provincial districts of Rome and Isernia, contacted thanks to the cooperation of the provincial offices for education. In these 200 classes, 40 children were diagnosed as having ADHD (consisting of a prevalence of around 0.8% in our study). Nine of these children did not participate in the study, resulting to a final sample of 31 children. They had all been officially diagnosed by the local health department, and all had the hyperactive form. The number of children under medical treatment is unknown because this data is private. However, it is highly plausible that this number is negligible given the meagre number of Italian children who joined the ADHD Registry for medical treatment. |

|

|

|

|

|

Табела 1. Учесници според полот и училишното ниво |

|

Table 1. Participants by gender and school level |

|

Процедури |

|

Procedures |

|

Што се однесува до децата со ADHD, откако училишните директори, наставниците и родителите дадоа дозвола да се изврши истражување, тие добија прашалник за време на часовите заедно со нивните соученици. Прашалниците пополнети од соучениците беа вклучени во општата база на податоци. |

|

As for the 31 children with ADHD, after the school managers, teachers and parents gave permission to conduct the inquiry; they received a questionnaire during school hours along with their classmates. Questionnaires filled in by classmates were included in the general database. |

|

|

|

|

|

Мерки |

|

Measures |

|

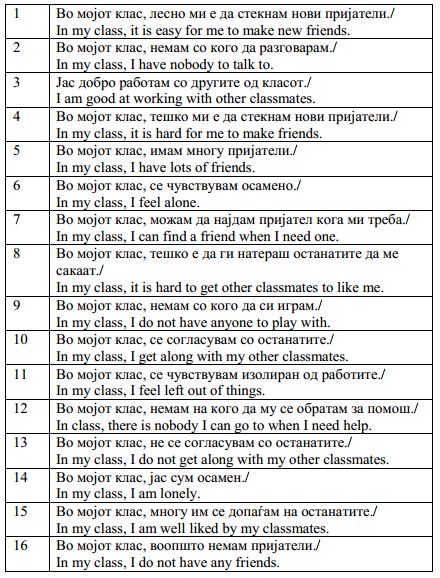

„Мерна скала за осаменоста на децата и општественото незадоволство“. Оваа мерна скала (37) е само-применлив прашалник за ученици/студенти на возраст од 6 до18 години. Тој содржи 24 прашања, од кои 8 се прашања за одвлекување внимание и се изоставени во конечниот резултат. Прашалникот го мери чувството на осаменост и општественото незадоволство. Некои прашања го испитуваат степенот до кој ученикот има пријатели во училиштето, и чувството да не биде сам. Други прашања го испитуваат степенот до кој ученикот може всушност да учествува во различни активности со неговите училишни другари (да разговара, игра, работи). |

|

The "Children's Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Rating Scale". This rating scale (37) is a self-administered questionnaire for pupils/students aged 6–18 years. It includes 24 items, 8 of which are distractor items and left out in the final score. The questionnaire measures the sense of loneliness and the social dissatisfaction. Some items inquire the extent in which the pupil has friends in the school, and the sensation not to be alone. Some other items inquire the extent in which the pupil can actually share diffferent activities with their schoolmates (to talk, to play, to work) |

|

|

|

|

|

Табела 2. Мерна скала „Осаменоста на децата и општественото незадоволство“ – Италијанска верзија на прашањата |

|

Table 2. Children’s Loneliness And Social Dissatisfaction Rating Scale – Italian version of the items |

|

Во студијата на Asher et al., прашалникот беше спроведен на 522 деца. Скалата од 16 прашања беше веродостојна (Кронбахова алфа = 0.90; Спирман-Браунов коефициент веродостојност = 0.91; Гутманов коефициент на веродостојност = 0.91). Различни социометриски анализи беа изведени во истата студија за да се испита врската помеѓу осаменоста и социометрискиот статус. Негативни значајни корелации помеѓу осаменоста и номинацијата најдобар пријател, како и помеѓу осаменоста и играта, беа откриени од страна на соучениците. Анализата на варијансата покажа дека децата без или со малку номинации искусиле и пријавиле значително повеќе осаменост отколку нивните поприфатени соученици. Кога се користат и двете – номинацијата најдобар пријател и скалата за играње, комбинирани да формираат индекс на популарност (непопуларни, просечни и популарни деца), односот со осаменоста беше помалку значаен, иако процентот на деца со висока осаменост беше значително поголем во непопуларната група. |

|

In the Asher et al. study, the questionnaire was administered to 522 children. The 16-item scale was found reliable (Cronbach’s alfa = 0.90; Spearman-Brown reliability coefficient = 0.91; Guttman split-half reliability coefficient = 0.91). Various sociometric analyses were performed in the same study to examine the relationship between loneliness and sociometric status. Negative significant correlations between loneliness and best friend nomination as well as between loneliness and play ratings received from peers were found. Analysis of variance showed that children with no or few nominations did experience and reported considerably more loneliness than their more accepted peers. When used both best friend nomination and play rating scales combined to form a popularity index (unpopular, average and popular children), the relation with loneliness was less prominent, though the percentage of children with high loneliness was considerably higher in the unpopular group. |

|

РЕЗУЛТАТИ |

|

RESULTS |

|

|

|

|

|

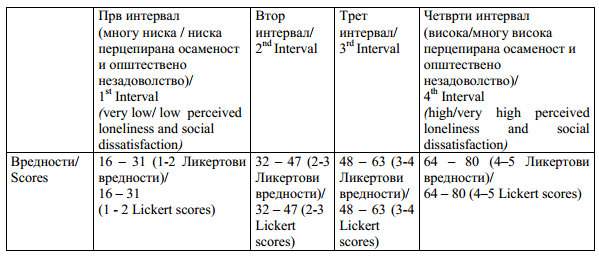

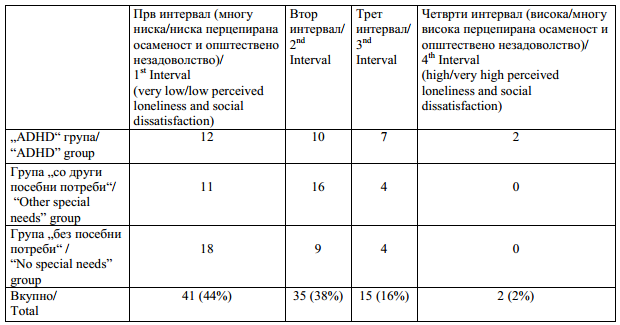

Интервалите на резултатите во табелата 3 покажуваат можен спектар на перцепирана осаменост и општественото незадоволство од минимум вредност од 16 (16 прашања од прашалникот имаа вредност 1 на Ликертовата скала – многу ниска перцепирана осаменост и општествено незадоволство) до максимум вредност од 80 (16 прашања од прашалникот имаа вредност 5 на Ликертовата скала – многу висока перцепирана осаменост и општествено незадоволство). Зачестеноста на дистрибуцијата на субјектите во четирите категории на перцепираното чувство на осаменост и општественото незадоволство е прикажана во табелата 4. |

|

Score intervals in Table 3 show the possible range of perceived loneliness and social dissatisfaction from a minimum score of 16 (16 items of the questionnaire scored 1 on the Lickert scale – very low perceived loneliness and social dissatisfaction) to a maximum score of 80 (16 items of the questionnaire scored 5 on the Lickert scale – very high perceived loneliness and social dissatisfaction). The frequency distribution of the subjects in the four categories of perceived sense of loneliness and social dissatisfaction is shown in Table 4. |

|

|

|

|

|

Табела 3. Мерна скала за осаменоста на децата и општественото незадоволство – Вредности на можниот опсег на перцепираната осаменост и општественото незадоволство |

|

Table 3. Children’s Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Rating Scale – The possible range of perceived loneliness and social dissatisfaction scores |

|

Табела 4. Дистрибуција на зачестеноста на учесниците во четирите категории на перцепирано чувство на осаменост и општествено незадоволство |

|

Table 4. Frequency distribution of the participants in four categories of perceived sense of loneliness and social dissatisfaction |

|

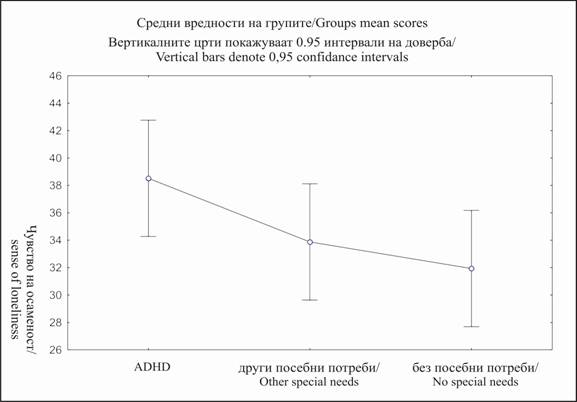

Според табелите 3 и 4, средните вредности на трите групи спаѓаат во вториот интервал, и на тој начин покажуваат ниска перцепирана осаменост и општествено незадоволство во класот. |

|

According to Tables 3 and 4, the mean scores of the three groups fell in the second interval, therefore showing low perceived loneliness and social dissatisfaction in class. |

|

|

|

|

|

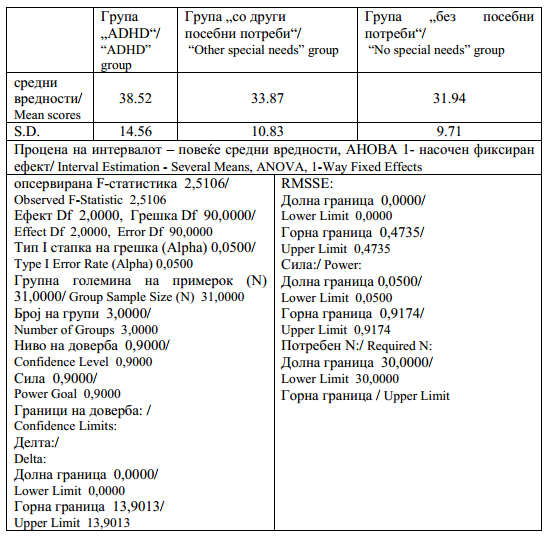

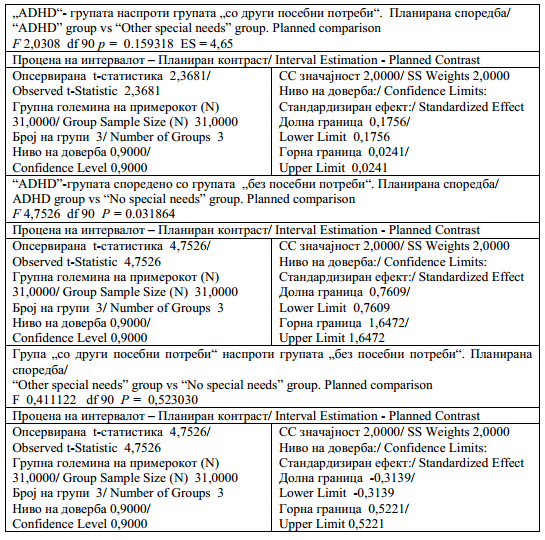

Табела 5. „ADHD“- група наспроти групата „со други посебни потреби“ наспроти групата „без посебни потреби“ на CLSDR-скалата средни вредности. Една насока ANOVA. F = 2,5106; p = 0.087 |

|

Table 5. “ADHD” group vs. “Other special needs” group vs. “No special needs” group on CLSDR Scale mean scores. One-way ANOVA. F = 2,5106 p = .087 |

|

Значајна разлика во средните вредности (табела 6) беше најдена помеѓу децата со ADHD и децата „без посебни потреби“. Како што се очекуваше, не беше најдена разлика помеѓу децата со „други посебни потреби“ и децата со „без посебни потреби“. Спротивно на она што се очекуваше, не беше најдена значајна разлика помеѓу децата со ADHD и децата „други посебни потреби“. Сепак резултатите (табела 4) исто така покажаа дека 30% од децата со ADHD вклучени во нашата студија (9/31) спаѓаат во третиот и четвртиот интервал (повисоки нивоа на перцепирана осаменост и општествено незадоволство), што беше двојно од фреквентните вредности на другите две групи. Не беа изведени статистички анализи бидејќи некои клетки имаа фреквентни вредности кои беа премногу ниски. |

|

A significant difference in mean scores (Table 6) was found between children with ADHD and children with “no special needs”. As expected, no difference was found between children with “other special needs” and children with “no special needs”. Contrary to what was expected, no significant difference was found between children with ADHD and children with “Other special needs”. However, results (Table 4) also |

|

|

|

|

|

Табела 6. „ADHD“-групата наспроти групата „со други посебни потреби“ наспроти групата „без посебни потреби“ на CLSDR-скалата средни вредности. Планирани споредби |

|

Table 6. “ADHD” group vs. “Other special needs” group vs. “No special needs” group on CLSDR Scale mean scores. Planned comparisons |

|

Слика 1. „ADHD“ група, „други посебни потреби“ група, „без посебни потреби“група на CLSDR Скалата |

|

Figure 1. “ADHD” group, “Other special needs”, “No special needs” group on CLSDR Scale |

|

|

|

|

|

Дискусија |

|

Discussion |

|

|

|

|

|

Конзистентно со повеќето студии, нашите резултати потврдуваат дека децата со ADHD покажуваат повисоки нивоа на изолација споредено со другите деца. Сепак, целосно инклузивната училишна средина се чини дека е генерален фактор во заштитата од изолација и општествено незадоволство. Средните вредности на ниска перцепирана осаменост и општествено незадоволство што ги покажаа сите групи, потврдувајќи ги резултатите од претходната студија (34), беа доста охрабрувачки кон засилување и поддршка на инклузивно ориентираните образовни системи. |

|

Consistently with most studies, our results confirm that children with ADHD show higher levels of isolation compared to other children. However, a fully inclusive school environment seems to be a general factor in protection from isolation and social dissatisfaction. The result that all groups showed mean scores of low perceived loneliness and social dissatisfaction, confirming the results of a previous study (34), was quite encouraging towards reinforcing and supporting the inclusive-oriented educational systems. |

|

|

|

|

|

Литература / References |

|

|

|

|

|

Share Us

Journal metrics

-

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 -

IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 -

SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 -

h5-index 7

h5-index 7 -

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

10 Most Read Articles

- PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE / REJECTION AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS WITH AND WITHOUT DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

- RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFE BUILDING SKILLS AND SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT OF STUDENTS WITH HEARING IMPAIRMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR COUNSELING

- EXPERIENCES FROM THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM – NARRATIVES OF PARENTS WITH CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN CROATIA

- INOVATIONS IN THERAPY OF AUTISM

- AUTISM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

- THE DURATION AND PHASES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- REHABILITATION OF PERSONS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY

- DISORDERED ATTENTION AS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL COGNITIVE DISFUNCTION

- DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDERS – AN OVERVIEW

- HYPERACTIVE CHILD`S DISTURBED ATTENTION AS THE MOST COMMON CAUSE FOR LIGHT FORMS OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY