JSER Policies

JSER Online

JSER Data

Frequency: quarterly

ISSN: 1409-6099 (Print)

ISSN: 1857-663X (Online)

Authors Info

- Read: 78774

|

РЕСУРСИ ЗА СЕМЕЈСТВОТО: ЗАБЕЛЕЖАНАТА СОЦИЈАЛНА ПОДДРШКА И ПРИЛАГОДУВАЊЕТО НА РОДИТЕЛИТЕ

Патриција ВЕЛОТИ

Оддел за клиничка и динамичка |

|

FAMILY RESOURCES: PERCEIVED SOCIAL SUPPORT AND PARENTS ADJUSTMENT

Patrizia VELOTTI

Department of Clinical and Dynamical Psychology- University of Rome |

|

Примено 02-01-2009 |

|

Received 02-01-2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

Вовед |

|

Introduction |

|

Добрата состојба на детето е во фокусот на грижата на различните политички, владини, училишни и истражувачки групи. Едно прашање коешто честопати го поставуваат овие групи се однесува на развојниот успех на децата и на ефективната помош за семејството во однос на интелектуалниот развој, менталното здравје и добросостојбата. |

|

The well-being of children has become a focal concern for a variety of political, governmental, school, and researcher groups. One question, often addressed by such groups, focuses on children's developmental success and the effectiveness of the family in assisting intellectual development, mental health and well-being. |

|

|

|

|

|

Метод |

|

Method |

|

|

|

|

|

Учесници |

|

Participants |

|

Примерокот се состои од 100 субјекти (50 двојки) со следниве социо-демографски карактеристики: просечна возраст на жените беше 35 години (СД=2.58), просечната возраст на мажите беше 38.17 (СД=4.53). Двојките беа контактирани за време на програмите за подготовка на семејството за новороденчето и службите за планирање и болниците во градот Рим. Двојките живеат заедно во просек 4.46 години (СД=1.14). 17.3 % не се венчани, додека останaтите 82.7 % се венчани (од кои, 30.8 % претходно не живееле заедно а 51.9% претходно живеeле заедно). |

|

The sample consisted of 100 subjects (50 couples) with the following socio-demographic characteristics: the average age of women was 35 years (SD = 2.58), the average age of men was 38.17 (SD = 4.53). Couples were contacted during the programs of Birth Preparation of the Family Planning Services and Hospitals of the Municipality of Rome. Couples living together by an average of 4.46 years (SD = 1.14). The 17.3% cohabiting, while the remaining 82.7% are married (in 30.8% of cases without preceding cohabitation and 51.9% after having lived together). |

|

Мерки |

|

Measures |

|

Интервју со возрасни придружници (ИВП; 20) е полуструктуирано интервју коешто го извлекува одговорот од меморијата на возрасните и овозможува расправа за искуството поврзано со придружникот за време на детството. Фокусот на ИВП е моменталната ментална состојба на испитаникот во однос на емоционалните врски коишто се проценуваат врз основа на кохеренцијата, а не врз основа на тоа дали се позитивни или негативни. Од системот на класификација произлегуваат три класификации на возрасните придружници (безбеден, напуштен и загрижен) засновани на мерењата на регистерот за искуствата со љубовта, одбивањето, сменетите улоги, напуштањето и притисокот да се стане родител и според скалата за менталната состојба (идеализација, недостаток на сеќавања, вклучен гнев, мисловна пасивност, страв од губење, намалување на достоинството, метакогнитивното набљудување и меѓусебната поврзаност на свеста и преписот). Индивидуалците коишто се класифицирани како безбедни покажуваат кохерентна концепцуализација во однос на своето искуство како придружници. Тие се отворени за соработка за време на интервјуто и можат да дискутираат и за позитивните и за негативните аспекти на својата приказна на објективен начин. Напуштените индивидуи се ограничени во однос на размислувањето за искуството поврзано со придружниците и емоциите. Тие овозможуваат генерално претставување на овие искуства коишто не се поддржани или дури и контрадикторни за време на интервјуто. Загрижените индивидуи изгледаат збунето и заплеткани во однос на минатите релации. Тие нудат прекумерна дискусија кога ги опишуваат искуствата со придружник и покажуваат особено негативни, честопати и испреплетени одговори кога се дискутира со нив (20). |

|

The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; 20) is a semi-structured interview that elicits the adult’s memories and discourse concerning attachment-related experiences during childhood. The focus of the AAI is the interviewee’s current state of mind regarding emotional relationships assessed on the basis of the account’s coherency rather than on the basis of whether they are positive or negative. The classification system yields three adult attachment classifications (secure, dismissing, preoccupied) based on coder-rated experiences of loving, rejecting, role-reversing, neglecting, and pressure to achieve parenting, and state of mind scales (idealization, lack of recall, involving anger, thought passivity, fear of loss, derogation, metacognitive monitoring, and coherence of mind and transcript). Individuals who are classified as Secure show a coherent conceptualization of their attachment experiences. They appear collaborative throughout the interview and can discuss both positive and negative aspects of their story in an objective manner. Dismissing individuals are restricted in thinking about attachment-related experiences and emotions. They provide generalized representations of these experiences which are unsupported or even contradicted throughout the interview. Preoccupied individuals appear confused and enmeshed in the past relationships. They offer excessive discourse when describing attachment experiences and show strong negative, often entangled, responses when discussing them (20). |

|

|

|

|

|

Резултати |

|

Results |

|

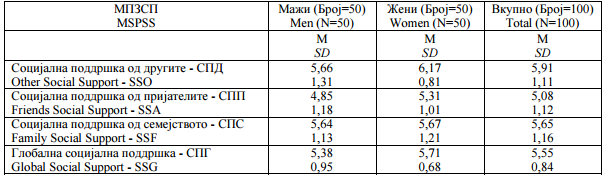

Жените (Табела 1) покажаа нивоа на забележана социјална поддршка и по раѓањето на своето прво дете којашто споредена со онаа на мажите беше значително повиска [F (1,99) = 3924, p =,05]. Скалата каде што се поизразени разликите е онаа на добиената социјална поддршка од страна на „Други кои се значајни“ („СПД“, во овој случај партнерот), каде за жените е во просек од 6,17, додека за мажите е 5,66 [F (1,99)= 5294, p = 024], дури и скалата за поддршка од пријателите („СПП“) покажува значителна разлика [F (1,99)= 4349, p = ,040]. Во спротивно на ова, кај скалата на забележаната социјална поддршка од семејството („СПС“) разликите не ги достигнуваат нивоата од статистичко значење. |

|

Women (Table 1) show levels of perceived social support after the birth of their first child significantly higher compared to men [F ( 1.99) = 3924, p = .05]. The scale where the differences are more marked is that of social support received by a “significant other” (“SCS" - in this case the partner), where for women there is an average of 6.17, while for men it is 5.66 [F (1.99) = 5294, p = .024]; even the scale of support from friends (“SSA") shows a significant difference [F (1.99) = 4349, p = .040]. On the contrary, on the scale of perceived social support from family (“SSF"), the differences do not achieve levels of statistical significance. |

|

Табела 1. Средни вредности и стандардни девијации од скалата на МПЗСП |

|

Table 1. Means and standard deviation of the MSPSS scale |

|

|

Придружник и забележаната социјална поддршка |

|

Attachment and Perceived Social |

|

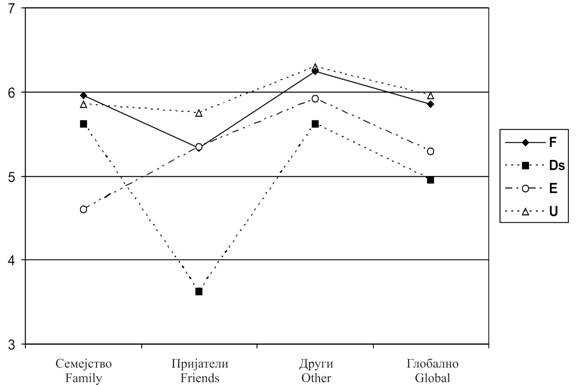

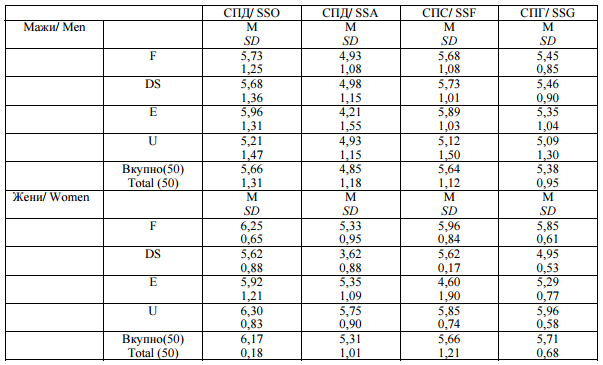

Кај мажите не е забележана статистички значајна асоцијација помеѓу моделот на придружник и забележаната социјална поддршка. Всушност, кај жените се забележаа позначајни разлики: моделите на придружник се поврзаа со различните перцепции за поддршка од семејството [F (3, 46) = 3838, p = .016], пријателите [F (3, 46) = 2314, p = .088], и глобално [F (3, 46) = 3079, p = .037], додека пак не постојат разлики кои што можат да се споредат со останатата, значително добиена поддршка (партнерот). |

|

Men do not reveal statistically significant associations between the model of attachment and perceived social support. Indeed, for women there are significant differences: the models of attachment were associated with different perceptions of support from family [F (3, 46) = 3838, p = .016], friends [F (3, 46) = 2314, p = .088], and global [F (3, 46) = 3079, p = .037], while there are no differences compared to other significant support received (partner). |

|

Табела2. Класификацијанапридружниците,средстватаи стандардните отстапки наМПЗСП. |

|

Table 2. Attachment classifications and MSPSS’s means and standard deviation. |

|

|

Анализирајќи ја дистрибуцијата на средствата добиени од жените (како што е прикажано во табела 2), можно е да се набљудува и да се заклучи дека класификацијата „загрижен“ е поврзана со пониските нивоа на забележаната социјална поддршка од семејстото (M = 4.60, SD = 1.90), додека класификацијата „напуштен“ е поврзана со пониските нивоа на поддршка од пријателите (M = 3.62, SD = .88) (види ја сликата 1). |

|

Analyzing the distribution of means obtained from women (as shown in Table 2), it is possible observe that the classification "Preoccupied" is associated with low levels of perceived social support from family (M = 4.60, SD = 1.90), while classification "Dismissing" is associated with lower levels of perceived support from friends (M = 3.62, SD = .88) (see Figure 1). |

|

|

|

Слика 1: Моделот на придружник кај жените и забележаната социјална поддршка. |

|

Figure 1: Women’s attachment models and perceived social support. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Заклучоци |

|

Conclusions |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Првата главна работа којашто ги засега нашите податоци се однесува на нивоата на откриената социјална поддршка. Податоците открија дека при раѓањето на детето, жените покажуваат повисоки нивоа на забележана социјална поддрша, додека пак некои истражувања (3; 5) ни сугерираат друг развој. Ова може да се разбере како последица на силно активирање кое се одредува преку првиот период од животот на детето, каде што контактите со семјството и пријателите, оние кои се во иста состојба, значително ги поврзаа жените меѓу себе со што добиваат поголема достапност. Во исто време социјалните промени во последните години, период за кој татковците постигнаа позначајна улога во однос на раѓањето на детето и прифатија задачи поврзани со грижата, делумно може да го променат овој резултат. |

|

A first point concerns our data regards the levels of social support found. Data revealed that at the child birth women show higher levels of perceived social support, while some studies (3; 5) suggest a different trend. This could be read as a consequence of strong activation determine by the first period of the child's life, where contacts with families and friends - who live similar circumstances - increased bringing women to receive around them greater availability. At the same time social changes of recent years, for which fathers achieved a more prominent role to concern the childbirth and the care giving tasks could partially make clear this result. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Citation:Velotti P. Perceived Social Support and Parents Adjustment. J Spec Educ Rehab 2008; 9(3-4):51-61. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Литература / References |

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

Share Us

Journal metrics

-

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 -

IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 -

SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 -

h5-index 7

h5-index 7 -

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

10 Most Read Articles

- PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE / REJECTION AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS WITH AND WITHOUT DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

- RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFE BUILDING SKILLS AND SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT OF STUDENTS WITH HEARING IMPAIRMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR COUNSELING

- EXPERIENCES FROM THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM – NARRATIVES OF PARENTS WITH CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN CROATIA

- INOVATIONS IN THERAPY OF AUTISM

- AUTISM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

- DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDERS – AN OVERVIEW

- THE DURATION AND PHASES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- REHABILITATION OF PERSONS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY

- DISORDERED ATTENTION AS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL COGNITIVE DISFUNCTION

- HYPERACTIVE CHILD`S DISTURBED ATTENTION AS THE MOST COMMON CAUSE FOR LIGHT FORMS OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY