|

Теорија на умот (ТоМ) е способност на човекот да го предвиди и да го опише своето однесување, како и однесувањето на другите. За да го постигне тоа, човекот ја користи својата ментална состојба, како што се: желбите, убедувањата, перцепцијата, емоциите (1). Со други зборови, децата што можат да ги разберат позитивните и негативните емоции на другите луѓе треба да остваруваат контакти со нив, да се социјализираат и да развиваат добри пријателски односи. Кога децата ќе станат свесни за своите знаења, интенции и убедувања и ќе ги разберат заблудите што произлегуваат од погрешните убедувања, тогаш ќе можат да ги разберат гледиштата на другите луѓе и да го прилагодат сопственото однесување (2). Lalonde и Chadler (3) изјавуваат дека ТоМ е способност неопходна за социјалните врски, а некои истражувања укажуваат дека теоријата на умот е поврзана со просоцијалното однесување. Еден од критериумите за дијагностицирање интелектуална попреченост ги вклучува недостатоците во адаптивното однесување, особено социјалното прилагодување (4). Подобрувањето на социјалните вештини бара специјални интервенции, бидејќи децата со интелектуална попреченост (ИП) имаат тешкотии при интеракција со своите врсници (5), а понекогаш покажуваат асоцијално однесување (6,7). Некои истражувања покажаа дека слабостите во верувањата од ТоМ кај децата со ИП се поврзани со нивните слаби социјални способности (8-10), а слабостите на емоциите од ТоМ се поврзани со ниските социјални вештини (11) и со недостатокот на социјално однесување во текот на социјалната интеракција (12). Кај децата со интелектуална попреченост (ИП), ТоМ ја претпоставува нивната општа прилагодливост, афективната прилагодливост, интеракцијата со врсниците и возрасните (2). Ова е содржано во истражувањето на Turk и Cornish (13), во коешто тие открија позитивни врски кај децата со ИП меѓу разбирањето на емоциите и социјалните вештини, социјалното однесување изразено во нивната интеракција во кооперативен, компетитивен контекст како што е просоцијалното однесување. Repacholi и Slaughter (14) покажаа дека добрата изведба на задачите на теоријата на умот резултира со подобрување на социјалните компетенции, додека дефицитот или одложувањето на развојот на теоријата на умот може да им наштети на социјалните функции на децата. Hughes и Leekman (15) потврдуваат дека развојот на теоријата на умот ги преобразува тесните врски на децата. Истражувањето на Moor, Barresi и Thompson (16) го покажа односот меѓу теоријата на умот на децата и нивната волја да го одложат моменталното задоволство заради воспоставување врски со другите. Децата со аутизам со проблеми во нивните социјални односи, покажуваат дефицит во реализирањето на задачите на ТоМ (18). Peterson и Siegel (19) откриваат дека популарните предучилишни деца постигнуваат повисоки резултати на теоријата на умот од нивните врсници коишто се отфрлени. Hughes, Dunn & White (20) известуваат дека оние што имаат тешкотии во нивните социјални релации постигнуваат пониски резултати на теорија на умот од контролната група. Некои истражувачи работеле на обука за некои задачи од ТоМ со различни групи деца. Amsterlaw и Wellman (21) и Appleton и Redy (22) ги обучувале малите деца да ги разберат погрешните верувања и откриле дека овие деца постигнале подобри резултати по обуката. Fisher и Happe (23) ги испитувале обуката за ТоМ и оперативното функционирање на децата со аутизам. Нивните резултати покажуваат дека децата добро напредуваат во функционирањето на ТоМ.

Терминот социјабилност сѐ почесто се користи последниве години за да се опишат бројните аспекти на социјалната интеракција и функционирањето. Постојат различни аспекти на поврзаните термини со социјабилноста (социјални вештини, социјално однесување, социјално функционирање, социјално осознавање, социјална компетенција), чиешто разбирање кај децата со интелектуална попреченост води кон разбирање на понатамошните тешкотии што можат да ги имаат (24). Моменталната верзија на ДСМ-5 спомнува три критериума за дијагностицирање интелектуална попреченост, во коишто социјабилноста или поврзаните термини (социјална партиципација, функ-ционирање во училиште и на работа) влегуваат во еден од овие критериуми (25).

Трајните врски се важни за развојот на детето, а ефикасното справување на детето со социјалниот свет произлегува од искуството во социјалните врски. Децата со интелектуална попреченост имаат проблеми со социјалните врски (26). Некои истражувачи ги проучувале задачите на ТоМ кај деца со интелектуална попреченост (27) и сознале дека голем процент (околу 60%) од нив имаат тешкотии со задачите од ТоМ. Иако почетно истражувањето беше фокусирано само на обука за придобивање и развивање на ТоМ, сепак се покажа дека обуката е ефикасна и води кон развивање на оваа способност (22,28).

Скорашните истражувања го испитуваат ефектот на теоријата на умот на социјалните вештини. Во едно истражување спроведено од Feng, Ya-yu, Tsai, Cartledge (29), тие ја разгледуваат теоријата на умот и социјалните компетенции на децата со аутизам и откриваат дека социјалните вештини на овие деца се значајно подобрени по обуката, којашто ги проширува нивните вештини и во ситуации од реалниот живот. Anneil (30) работел на теоријата на умот за да ја зголеми социјалната компетенција на децата со аутизам. Резултатите покажале дека, следејќи ја обуката, сите деца ја достигнале теоријата на умот и дека има значајно подобрување во нивните социјални интеракции и социјалните игри.

Многу деца со задоцнет развој, како што се оние со интелектуална попреченост и аутизам, имаат потреба од структуирана и сеопфатна обука за учење на многу основни вештини (31). За овие деца, некои подрачја од социјалното однесување се тешки за усвојување без обука. Направени се напори за подобрување на адаптивното однесување на децата со аутизам основано на методите што потекнуваат од бихеjвиоризмот. Метаанализата спроведена од Spreckley и Boyd (32) покажа дека овие методи не се ефикасни и не се постигнуваат значајни промени во однесувањето на децата со аутизам. Проблемите со однесувањето на децата со аутизам, особено во сферата на интеракција со другите, биле оставени како мистерија сѐ до 1985, кога Baron-Cohen и неговите колеги (18) ги претставија овие проблеми како резултат на нарушување на теоријата на умот.

Когнитивната попреченост и адаптивното однесување ја објаснуваат причината за проблемот кај децата со интелектуална попреченост (33). Всушност, тие се суштинскиот критериум во дијагностицирањето на интелектуалната попреченост. Социјабилноста и социјалното прилагодување се многу важни, зашто човековото однесување зависи од интеракцијата меѓу луѓето и средината (34). Иако важноста на социјабилноста е недвосмислена, не е направено многу во оваа област што е поврзано со развојот на задачите на ТоМ за лицата со интелектуална попреченост. Изведена е некаква интервенција базирана на бихеjвиоралната теорија, нагласувајќи ги средината и нејзиното зајакнување, а не когнитивните способности. Ако проблемите во врските на лицата со интелектуална попреченост можат да произлезат од дефицитот на задачите на ТоМ, дали обуката за ТоМ ќе им помогне на овие деца во остварувањето на задачите на ТоМ и ќе ги подобри нивната социјабилност и социјалните врски?

|

|

Theory of mind (ToM) is an ability in human beings which enables individuals to predict and describe his/her behaviors, as well as others people’s behaviors. To do this, he/she uses the mental states such as desires, beliefs, perceptions, emotions (1). In other words, children who can understand other people’s positive and negative emotions should be able to interact with them, be socially responsive and develop good relationships. Through acquiring the knowledge, intentions and beliefs and understanding false beliefs, will understand other people’s perspective and adjust their own behavior (2). Lalonde & Chadler (3) stated that ToM ability is necessary for social relationships and some research has indicated that ToM is related to pro social behaviors. One of the criteria for diagnosing intellectual disability includes deficits in adaptive behaviors, especially social adjustment (4). Improving social skills is a majore concern in special interventions, because children with intellectual disabilities (ID) experience difficulties in interacting with peers (5), and sometimes display anti-social behaviors (6,7). Some studies have shown that weaknesses in ToM beliefs in children with ID are linked with their low social abilities (8-10) and that their weaknesses in ToM emotions are linked with low social skills (11), and with their less social behavior during social interactions (12). In children with intellectual disability (ID), ToM predicts their general adaptation, affective adaptation, interactions with peers and adults (2). This is consistent with the Turk & Cornish study (13) in which they found positive links between the understanding of emotions and social skills in children with ID, and social behaviors displayed in their interactions in cooperatiing competitive contexts such as prosocial behavior. Repacholi and Slaughter (14) expressed that good performance on theory of mind tasks results in an increase of social competence, while deficit or delay in the development of the theory of mind can be harmful for the social functions of children. Hughes and Leekman (15) states that development in theory of mind transform children’s close relationships. Moor, Barresi & Thompson’s study (16) showed the relationship between the theory of mind of children and their willingness to delay instant gratification for the purpose of making relationships with others. Autistic children with problems in their social relations, have deficits in their ToM tasks (18). Peterson and Siegel (19) discovered that popular pre-school children earned higher scores in theory of mind than their peers who had been sidelined. Hughes, Dunn & White (20) reported that those who have difficulties in their social relations acquire lower scores in theory of mind than the control group. Some researchers have worked on the training of some ToM tasks in different groups of children. Amsterlaw & Wellman (21) and Appleton & Redy (22) trained young children to understand false beliefs and they found out that children did better in this task after the training. Fisher and Happe (23) studied the ToM training and operational functioning in autistic children. Their results showed that children had good progress in ToM functioning.

The term sociability has been used more frequently in recent years to describe numerous facets of social interaction and functioning. There are various aspects or related terms of sociability (social skills, social behavior, social functioning, social cognition, social competence and understanding them in children with intellectual disability leads to understand the future difficulties these children might encounter (24). The current version of the DSM-5, mentions three criteria for diagnosing intellectual disability and sociability or related constructs (social participation, functioning at school and work) is one of them (25).

Enduring relationships are important for the development of children and a child’s effectiveness in dealing with the social world comes from experiences in social relationships. Children with intellectual disabilities have problems with their social relationships (26). Some researchers have studied the ToM tasks in children with intellectual disabilities (27) and found out that high percentage (about 60 percent) of these children have difficulties with their ToM tasks. Although initial research was focused on training only for the acquisition and development of ToM, some showed that training was effective and led to the development of this ability (22,28).

Recent studies have considered the effects of theory of mind training on social skills. In a study conducted by Feng, Ya-yu, Tsai, Cartledge (29), the theory of mind training and social competence of autistic children was considered and they found that the social skills of these children improved significantly after trainings that extended their skills to real life situations. Anneil (30) worked on theory of mind to increase the social competence of children with autism. The results showed that following the training, all children reached the theory of mind and there was significant improvement in their social interactions and social play.

Most children with developmental delays, such as the intellectually disabled and autistic, require structured and comprehensive training in order to learn most basic skills (31). There are some areas in social behavior which these children find difficult to learn without any training. Efforts have been made to improve the adaptive behavior of autistic children based on methods derived from behaviorism. The meta-analysis conducted by Spreckley and Boyd (32) showed that these methods were not effective and have not succeeded in creating significant changes in the behavior of autistic children. Behavioral problems in autistic children, especially in the area of interacting with others, remained a mystery until 1985, when Baron - Cohen and his colleagues (18) introduced these problems as a result of violations of theory of mind.

Cognitive disability and adaptive behavior explain the problem-causing behavior of children with intellectual disabilities (33). In fact, these are the essential criteria to diagnose intellectual disability. Sociability and social adjustment are essential because the human function depends on the interaction between humans and their environments (34). Even though the importance of sociability is clear, there is still much work to be done in this area, regarding the development of ToM tasks for the intellectually disabled. Some interventional work has been done based on behavioral theory, with emphasis on environment and environmental reinforcements, rather than on cognitive abilities. If the relationship problems in the intellectually disabled could be the result of ToM task deficits, would the ToM training help these children acquire ToM tasks and improve their sociability and social relationships?

|

|

За ова истражување беше користена експерименталната метода на преттестирање и посттестирање. Нашиот примерок вклучува 30 ученика од машки пол со интелектуална попреченост (15 во експерименталната, 15 во контролната група) и 30 ученика од женски пол (како и момчиња) од посебни основни училишта. Учесниците се способни за образование и можат вербално да комуницираат. Учениците мораше да исполнуваат некои критериуми за учество во истражувањето. Критериумите беа: резултатот на учениците на тестот за теорија на умот, којшто требаше да биде 19 или помалку, и резултатот од тестот за интелигенција, којшто требаше да биде меѓу 50-70, мерено според Векслеровата скала за интелигенција на децата - прочистен текст (WISC-R). Исто така, беше потребна согласност на еден од родителите за учество на детето во истражувањето.

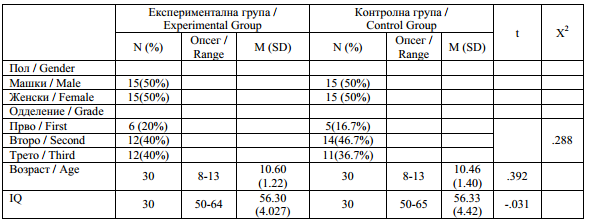

Во табелата 1 се прикажани некои демографски информации за експерименталната и за контролната група. Средната вредност на возраста и IQ кај експерименталната група изнесува M=10.60 и M=56.30, а за контролната група M=10.46 и 56.33. Бројот на момчиња и девојчиња и одделенијата што ги посетуваат, се прикажани за секоја група.

|

|

An experimental method with a pre test and a post test was used for this study. Our sample included of 30 male students with intellectual disability (15 in the experimental group, 15 in the control group) and 30 female students (the same as male) from special primary schools. The participants were educable and they could communicate verbally. These students had to meet some criteria for entering the study. The criteria were: student’s score in the theory of mind test, which might have been 19 or less and the intelligence score, which should have been between 50-70, as measured by Wechsler Intelligence Scale for children Revised (WISC-R). Furthermore, at least one of the parents had to give consent for their child’s participation in the study.

Table 1 shows some demographic information for the experimental and control groups. The mean for age and IQ of the experimental group was M=10.60 and M=56.30 and for the control group it was M=10.46 and 56.33. The number of boys and girls and the grades in which they are in, are presented in each group.

|

|

Во ова истражување беа употребени следниве инструменти:

- 38-степениот тест за ТоМ, Векслеровата скала за интелигенција на децата – прочистен текст (WISC-R) и Винеландовата скала за адаптивно однесување;

- 38-степениот тест за ТоМ: главниот образец на оваа скала е создаден од Muris и сор. (33). Создаден е на основа на мултидимензионални и развојни погледи, пристапувајќи кон покомплексни и напредни аспекти на теоријата на умот и покривајќи повеќе возрасти во споредба со претходните видови тестови. Тестот има три супскали:

Основно ниво на теорија на умот: прво ниво на ТоМ или препознавање и предвидување на емоциите (содржи 20 прашања или точки

Прва манифестација на вистинската ТоМ: второ ниво на теорија на умот или првично верување и разбирање на погрешното убедување (вклучува 13 точки).

Понапредни аспекти на теоријата на умот: трето ниво на ТоМ и второстепено верување, разбирање хумор (содржи 5 точки).

Овој тест се спроведува индивидуално и содржи слики и приказни коишто им се презентирани на учесниците. На субјектите им беа дадени прашања. „1“ за точен одговор, а „0“ за погрешен одговор. Субјектите можат да освојат од 0 до 38 поени. Повисокиот резултат значи дека субјектот постигнува повисоко ниво на теорија на умот (35). Тестот е, исто така, стандардизиран во рамките на иранското општество од Ghamarani, Alborzi & Khayyer (36) во група ученици со интелектуална попре-ченост. За валидноста беше употребено: логичката важност, корелацијата на суптестовите со вкупниот резултат и конкурентна валидност. Коефициентот на корелација на суптестовите и вкупниот резултат од тестовите беа значајни и се движеа во опсег од 0.82 до 0.96. Веродостојноста беше проценета со средната вредност на тестирањето-ретестирањето и Кромбаховата алфа (Chronbach's α). Тестирањето-ретестирањето варираше од 0.70 до 0.94. Внатрешната конзистентност за комплетното тестирање и за секој суптест беше проценета на: 0.86, 0.72, 0.80 и 0.81, соодветно. Коефициентот на веродостојност беше проценет на 0.98 (36).

- Векслеровата скала за интелигенција на деца – прочистен текст ги опфаќа супскалите што се уредени индивидуално давајќи три резултата за интелигенцијата: вербална интелигенција, невербална интелигенција и вкупна интелигенција. Персиската верзија на тестот беше направена за децата од општата популација на возраст од 6 до 13 години. Методата раздели на половина за вербалните и невербалните суптестови (изземајќи го опсегот на бројките со два различни дела и кодирајќи дека тоа е тест за брзина) беше пресметана со коефициентот на корелација на Спеармен Браун и се движеше од 0.42 до 0.98. Просекот на коефициентот изнесува 0.69. Коефициентот на веродостојност беше определен со средната вредност на тестирањето-ретестирањето во опсег од 0.44 до 0.94, а забележавме помалку од тоа само во кодирањето и на аритметичките супскали. Средната вредност на коефициентот кај неа изнесува 0.73 (37). За да се измери валид-носта, Shahim (37) го споредил тестот со Векслеровиот тест за училишни и предучилишни деца: 0.84, 0.74 и 0.85, соодветно.

За да се избегне можноста за преклопување на тестовите за ТоМ и за интелигенција, учесниците беа поделени соодветно во две групи. Во едната група, прво беше завршен тестот за интелигенција, а потоа тестот за теорија на умот. Во другата група, прво беше завршен тестот за теорија на умот, а по него следуваше тестот за интелигенција. Споредувајќи ги двете групи, ниту еден од тестовите не си влијаеја меѓусебно.

Винеландова скала за адаптивно однесување: оваа скала е подготвена и претставена од Edgardal, а содржи 117 точки (прашања). Винеландовата скала за адаптивно однесување е направена за проценка на лицата со попреченост и без попреченост од раѓањето до староста во нивното лично и социјално функционирање. Тие се организирани околу четири домени на однесување: комуникација, секојдневни вештини, социјализација и моторни вештини, од коишто ние во ова истражување се фокусираме на социјализацијата. Во нашето истражување, беше интервјуиран еден од родителите на дете со интелектуална попреченост. Во ова истражување беше употребена Винеландовата скала што беше стандардизирана во Иран од Barahani (38). Веродостојноста беше добиена од ретестирањето на главните области на скалата, кои беа од 0.85 до 0.95. Валидноста беше измерена преку валидноста на содржините на скалата, коишто се движеа од 0.85 до 0.90. Валидноста беше измерена со логичката валидност на скалата, со прогресот на Винеландовата развојна скала за различни возрасни групи и со просечен резултат за 100 примероци (50 со интелектуална попреченост и 50 со нормален развој). Зголемувањето на резултатите за различните возрасни групи и значајната разлика на просечната вредност на резултатите на двете групи (интелектуално попречени и нормални деца) укажува на валидноста на содржините на скалата (38).

|

|

The instruments used in this study were:

- A 38-item ToM test, the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for children Revised (WISC-R), andVineland adaptive behavior scale

- 38-item ToM test: the mainframe of this test was designed by Muris and et al. (33). This was constructed on the basis of a multidimensional and developmental view, assessing more complex and advanced aspects of TOM and covering a wider range of ages in comparison with earlier types of the test. The test has three sub-scales:

The primitive level of theory of mind (TOM): first level of TOM or recognition and prediction of emotions (Contains 20 questions or items).

First manifestations of a real TOM: Second level of TOM or first-order of belief and understanding of false belief (includes 13 items).

More advanced aspects of theory of mind (TоM): third level of TоM and second-order of belief, understanding the humor (Contains 5 items).

This test is administered individually containing images and stories هايي مي باشد كه آزماينده بعد از ارائه آنها به آزمودني، سوالات استانداردي را مطرح مي كند و به پاسخ صحيح آزمودني نمره «1»، و به پاسخ غلط وي نمره «0» مي دهد.which are presented to the participant. The questions are given to the subjects. The score of "1" is considered for the correct answer and the score of "0" for the wrong answer. در كل آزمون، آزمودني نمرهاي بين 0 تا 38 دريافت مي كند.The subjects can earn scores ranging from 0 to 38. نمرات بالاتر نشانه دسترسي به سطوح بالاتر نظريه ذهن است (قمراني، البرزي و خير، 1385). A higher score means that the subject assented to a higher theory of mind level (35). The test also was standardized within Iranian society by Ghamarani, Alborzi & Khayyer (36) in a group of students with intellectual disabilities. The content validity, the correlation of sub-tests with total score, and concurrent validity were used for validation. The correlation coefficient of sub-tests and the total test scores were all significant and varied in the range of 0.82 to 0.96. The reliability was assessed by the means of test-retest and Chronbach's α. Test-retest varied between 0.70 and 0.94. Internal consistency for total test and each sub-test was estimated at: 0.86, 0.72, 0.80, and 0.81 respectively. The reliability coefficient wasبدست آمده است (قمراني، البرزي و خير، 1385). estimated to be 0.98 (36).

-Wechslerintelligence Scale for Children –Revised:encompasses the sub-scales that are administered individuallygiving three intelligence scores: verbal intelligence, non-verbal intelligence and total intelligence. A Persian version of the test was built for normal children between the ages 6 and 13. The Split-half method for verbal and non-verbal sub-tests (excepted for digit span with two different parts and coding that is a speed test) was calculated by the Spearman Brown correlation coefficient and fluctuated between 0.42 and 0.98. The coefficient mean was 0.69. The reliability coefficient was assessed by means of test-retest which ranged from 0.44 to 0.94 and we observed less than that only in coding and Arithmetic sub-scales. Its coefficient mean was 0.73 (37). Tomeasure the validity, Shahim (37) compared the test with the Wechsler test for school and pre-school children: 0.84, 0.74, and 0.85 respectively.

To avoid probability of interplay between ToM and intelligence tests, the participants were randomly divided into two groups. In one group, the intelligence test was done first and then the TOM test. In another group, the TOM test was performed first and was followed by the intelligence test. When the two groups were compared, it was ascertained that neither of the tests influenced each other.

Vineland adaptive behavior scale: This scale is prepared and represented by Edgardal and it is consisted of 117 items (questions).The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) were designed to assess handicapped and non-handicapped persons from birth to adulthood in their personal and social functioning. The VABS is organized around four Behavioral Domains: Communication, Daily Living Skills, Socialization, and Motor skills. In this study we focused on socialization. In our study, one of the parents of the children with intellectual disability was interviewed. The Vineland scale which was standardized in Iran by Barahani (38), was used in this study. The reliability was obtained from retesting the major areas in the scale, which were 0.85 to 0.90. The validity was measured by the contents validity in the scale, the progress of Vineland’s developmental scores in different age groups, and the mean score of 100 samples (50 with intellectual disability and 50 with normal ones). The increase in the scores for different age groups and the significant difference in the mean score of the two groups (intellectually disabled and normal children) indicates the validity of the scale contents (38).

|

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 h5-index 7

h5-index 7 Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68