JSER Policies

JSER Online

JSER Data

Frequency: quarterly

ISSN: 1409-6099 (Print)

ISSN: 1857-663X (Online)

Authors Info

- Read: 77058

|

РОДИТЕЛИ НА ДЕЦА СО ПРЕЧКИ ВО РАЗВОЈОТ: СТРЕС И ПОДДРШКА

Наташа ЧИЧЕВСКА-ЈОВАНОВА Даниела ДИМИТРОВА-РАДОЈИЧИЌ

Институт за дефектологија Филозофски факултет Скопје, Македонија

|

|

PARENTS OF CHILDREN WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES: STRESS AND SUPPORT

Natasha CHICHEVSKA JOVANOVA Daniela DIMITROVA RADOJICHIKJ

Faculty of Philosophy

|

|

Примено: 05.12.2012 Прифатено: 11.02.2013 UDK: 364-787.3-053.52:159.922.76-056.34

|

|

Recived: 05.12.2012 Accepted: 11.02.2013 Original Article |

|

|

|

|

|

Вовед |

|

Introduction |

|

|

|

|

|

Семејството е незаменлива средина во која детето се формира како личност, во која живее задоволувајќи некои од неговите најважни потреби кои можат да се задоволат само во семејството. Иако ни се чини дека за семејството знаеме сѐ, неговото научно проучување не е едноставно, така што во оваа област постојат низа неразрешени прашања и проблеми – почнувајќи од историскиот развој на семејството, преку неговата структура и функција, односите кон општеството, внатрешните односи и динамика. Сѐ она што важи за семејството и улогата на родителите во развојот на детето што не е попречено во развојот, важи и за родителите кои имаат дете со пречки, со тоа што родителите на ова дете имаат и специфични проблеми кои другите родители ги немаат или ги немаат во толкав обем, тежина и разновидност. Детето со пречки во развојот од родителот бара многу повеќе време и внимание во споредба со детето без пречки. Родителите кога ќе дознаат дека нивното дете има пречки во развојот, животот целосно им се менува и тие ќе мораат да се справат со многу стресови. Многу истражувања покажуваат дека овие родители доживуваат поголем стрес отколку родителите на децата без пречки во развојот (1–7). Пред сѐ, тие мораат да ги променат очекувањата кои ги имале за своето дете, да се справат со дополнителните финансиски трошоци (плаќање на лекови, дополнителни третмани, приватни часови, превоз), како и со социјалната стигма поврзана со попреченоста на нивното дете (8–10). Многу често едниот родител (најчесто мајката) е принуден да се откаже од работата поради потребата од интензивна грижа за детето. Дел од нив можеби ќе се соочат и со социјална изолација од поширокото семејство, соседите и пријателите (11– 13). На многу родители им се потребни месеци, а на некои и години додека да се помират со фактот дека имаат дете со пречки во развојот. Таа состојба и кризата што настанува, тешко може да се спречи, но можат да се олеснат тешкотиите на родителите. Ним им е потребна емотивна поддршка и информираност. Ова е процес кој долго трае. Семејството е прво кое треба да го прифати детето со пречки во развојот. За повеќето родители искуството да се израсне дете со пречки во развојот е многу стресно. Други, се справуваат со проблемот создавајќи нереална слика (било да е позитивна или негативна) или ги занемаруваат ограничувањата кај нивното дете. Постојат и родители кои реално ја прифаќаат состојбата на детето и се посветени, весели, имаат надеж, самодоверба и гордост (3, 4, 14, 15). Bower и Hayes во 1998 година истакнувале дека семејствата на децата без и со пречки во развојот имаат повеќе заеднички карактеристики отколку разлики (16). Употребата на позитивните стратегии за справување со стресот влијае на намалување на стресот кај родителите на децата со пречки во развојот (17). Според Lustig, оние семејства кои ја реформулираат попреченоста на своето дете на позитивен начин и себеси се сметаат како компетентни, а не како пасивни актери, имаат подобро семејно прилагодување (18). Сè повеќе родители на децата со пречки во развојот, покрај стресот, реферираат дека доживеале и лична трансформација (19). Во својата анализа на објавените истражувања за природата и структурата на позитивни перцепции на семејствата со деца со пречки во развојот, Hastings и Taunt (20) ги сумираат како: (1) задоволство/сатисфакција во обезбедување грижа за детето, (2) детето како извор на радост/среќа, (3) чувство дека направиле најдобро за детето, (4) споделување љубов со детето, (5) обезбедување можност за детето да учи и да се развива, (6) зајакнување на семејството и/или бракот, (7) дава нова цел во животот, (8) развој на нови вештини, способности или нови можности за кариера, (9) станува подобра личност (повеќе внимателна, помалку себична, повеќе толерантна), (10) зголемена лична сила или самодоверба, (11) проширена социјална и општествена соработка, (12) зголемена духовност, (13) изменета перспектива на животот (на пример: она што е важно во животот, поголема свесност за иднината) и (14) живеење со побавно темпо. Најновите истражувања за семејствата на децата со пречки во развојот се однесуваат на можните стратегии за подобрување на квалитетот на животот на родителите и нивните деца, а не на негативните ставови кон инвалидноста (21). Нашето истражување делумно е насочено кон испитување на овие ставови, бидејќи кај нас овие прашања досега не се истражени. |

|

The family is an irreplaceable environment where the child is formed as a person, where he/she lives satisfing some of his/her most important needs that can be satisfied only within the family. Although we sometimes feel that we know everything about the family, its scientific background is not simple at all, therefore there is a list of unresolved questions and problems – starting from the historical family development all the way to its structure and function, the relations towards the society, the internal relations and dynamics. Everything that is valid for family and parents’ role in the development of the child without any disabilities, is also valid for parents of child with developmental disabilities, in addition to which these parents have other specific problems that other parents do not have or they have them much less. A child with developmental disabilities requires a lot more time and attention from its parent in comparison to other children. Parents’ lives are turned upside down at the moment they find out that they have a child with developmental disabilities and they have to cope with a lot of stress. A lot of researches state that these parents experience bigger stress than the parents of normal children (1-7). At first, they have to alter their expectations about their child, to cope with the additional financial issues (paying for medicine, additional treatments, tutoring, transportation), as well as social stigmatization related to their child’s disability (8–10). Quite often one of the parents, usually the mother, must quit her job because of providing an intensive child’s care. Some of them might face a social isolation by their family, neighbors and friends (11–13). A lot of parents need months and some of them even years to accept the fact that they do have a child with developmental disabilities. The condition and the crisis that occur are very hard to be prevented; however the parents’ difficulties could be facilitated in a way. They need a lot of emotional support and information. It is a process that takes a long time. The family is the first that needs to accept the child with developmental disabilities. For most of the parents the experience of raising a child with disabilities is extremely stressful. Others try to cope with the problem by creating a surreal image (no matter if it is a positive or a negative one) or they ignore the disabilities of their child. There are also parents who really accept their child’s state and they are dedicated, cheerful and they have a lot of self-confidence and pride (3, 4, 14, 15). In 1998, Bower and Hayes pointed that families of children with and without developmental disabilities have more common characteristics than differences (16). Usage of positive strategies for dealing with the stress, affects reducing the stress in parents of children with developmental disabilities (17). According to Lustig, those families which reformulate their child’s disability in a positive way and consider themselves as competent, have better family adaptation (18). More and more parents of children with developmental disabilities refer that beyond stress, they also have experienced a personal transformation (19). In their own analysis of the published research studies about the nature and structure of the positive perceptions of the families with children with developmental disabilities, Hastings and Taunt (20) summarized as: (1) pleasure / satisfaction in providing care for the child, (2) the child as a source of joy / happiness, (3) feeling that they did the best for the child, (4) sharing love with the child, (5) providing possibilities for child’s learning and growth, (6) strengthening the family and/or marriage, (7) gives a new life goal, (8) development of new skills, capabilities or new career opportunities, (9) becomes a better person (more careful, less selfish, more tolerant), (10) increased personal strength and self-confidence, (11) extended social and societal cooperation, (12) increased spirituality, (13) changed life perspective (e.g. what is important in the life, more aware for the future) and (14) living with slower beat. Recent research studies about the families of children with developmental disabilities refer to the possible strategies for improvement of the life quality of the parents and their children, and not to the negative attitudes toward the disability (21). Our study is partially directed towards examination of these attitudes, because in our country these questions have not been investigated yet. |

|

|

|

|

|

Цел на истражувањето |

|

The purpose of the research |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Методологија на истражувањето |

|

Methodology of the research |

|

|

|

|

|

Примерок |

|

Sample |

|

Во истражувањето беа опфатени 31 родител на 31 дете со пречки во развојот кои се едуцираат во посебни училишта, односно имаат сериозни интелектуални, визуелни или моторни нарушувања. Од нив, 22 (71%) беа мајки и 9 (29%) татковци, на возраст од 23 до 58 години (40,25+6,73 години). Повеќето од родителите се во брак (29 или 93,5%). Дваесет анкетирани родители или 64,6% имаат завршено средно образование, шест (19,3%) основно, четири (12,9%) високо и еден (3,2%) вишо образование. Со цел да го утврдиме социоекономскиот статус на овие семејства, родителите беа запрашани дали тие и нивните брачни партнери се во работен однос. Од анкетираните 9 татковци, вработени се 6 (66,6%), а од 22 анкетирани мајки, 5 (22,7%) се во работен однос. Збирно, од 29 потполни семејства, кај 9 (31%) семејства вработени се и двајцата родители, кај 11 семејства или 38% работи само едниот родител и кај останатите 9 семејства (31%) невработени се и двајцата родители. Останатите двајца самохрани родители се невработени. |

|

Thirty one parents and 31 children with developmental disabilities who go to special primary schools and have serious intellectual, visual and motor impairments were included in the research. 22 of them (71%) were mothers and 9 (29%) were fathers at the age between 23 and 58 years (40,25+6,73 years). Most of the parents were married (29 or 93,5%). 20 of the inquired parents or 64,6% have high school degrees, 6 (19,3%) have elementary school degrees, 4 (12,9%) have BA and 1 (3,2%) have junior college degree. In order to determinate the social-economic status of these families, the parents were asked whether they or their spouses are employed. 6 of 9 inquired fathers were employed (66,6%) and from 22 inquired mothers, 5 were employed (22,7%). In total, from 29 complete families, in 9 families (31%) both of the parents are employed; in 11 families (38%) only one parent is employed and in the other 9 families (31%) both parents are unemployed. The other 2 single parents are unemployed. |

|

|

|

|

|

Време и место на истражување |

|

Time and place of the research |

|

Истражувањето беше спроведено во март 2011 година во Скопје. Беа опфатени 11 (35,5%) родители на деца со интелектуална попреченост од Посебното основно училиште „Д-р Златан Сремац“, 12 (38,7%) родители на деца со церебрална парализа од Дневниот центар за згрижување на лица заболени од церебрална парализа и 8 (25,8%) родители на деца со оштетен вид од Државното училиште за рехабилитација на деца и младинци со оштетен вид „Димитар Влахов“. |

|

The research was conducted in March 2011 in |

|

|

|

|

|

Инструменти и техники на истражувањето |

|

Instruments and techniques of the research |

|

За потребите на истражувањето користевме посебно изготвен прашалник составен од 22 прашања поделени во три дела. Првиот дел се состоеше од четири прашања на кои родителите требаше да одговорат: дали знаат какви пречки во развојот има нивното дете; кога, кој и како им соопштил за попреченоста на нивното дете. Во вториот дел беа користени само 7 прашања од прашалникот FSCI (Family Stress and Coping Interview) (Интервју за справување со стресот во семејството), со цел да се измери степенот на стрес кај семејствата (22). Од родителот се бараше да го рангира степенот на стрес за секое прашање посебно, користејќи ја Петстепената Ликертова скала. Во третиот дел за утврдување на степенот на поддршка на родителите користевме дел, односно 11 од 45-те прашања од FSS (Family Support Scale) (Скала за процена на поддршката во семејството) (23). Родителите требаше да го рангираат степенот на поддршка со користење на Четиристепената Ликертова скала (0 - никаква; 1 - повремена; 2 - голема; 3 - многу голема). Причини зошто не беа користени комплетните оригинални прашалници (FSCI и FSS) се непостоењето на соодветни ресурси за поддршка на семејствата на децата со пречки во развојот (на пример, недоволно развиена мрежа на рана интервенција, професионална поддршка на семејството и др.), како и културните и социјалните специфичности на семејствата во нашата држава. Откако родителите се согласија да учествуваат, им беа поделени прашалници со претходно објаснување на целта и постапката на истражувањето. |

|

For the research’s needs, a specially prepared questionnaire with 22 questions divided in three sections, was used. The first section included four questions that parents needed to answer: do they know what kind of disabilities their child has; when, who and how were they informed about their child's situation? In the second section there were only 7 questions from the FSCI questionnaire (Family Stress and Coping Interview), in order to examine the stress level (22). The parents were asked to rate the stress for each question, using the five level Likert Scale (0- it was not stressful, 1 – a little stressful, 2 – stressful, 3 – very stressful and 4 – extremely stressful). In the third section for confirming the level of support, we used part of the questions i.e. 11 questions out of 45 were taken from the FSS (Family Support Scale) (23). Parents were supposed to rate the support level by using the four level Likert Scale (0 – no support at all; 1 – rare support; 2 – big support, 3 – very big support). Lack of adequate resources for support of the families of children with developmental disabilities (e.g. insufficient developed network of early intervention, professional support for the family) as well as cultural and social specificities of the families in our country, are the main reasons why complete original questionnaires (FSCI and FSS) were not used in the research. After the parents confirmed their participation in the research, they were given the questionnaires with a previous explanation of the aim and the methods of the research. |

|

|

|

|

|

Статистичка анализа |

|

Statistical analysis |

|

По собирањето на податоците, истите беа групирани, табелирани, обработени и графички прикажани со програмот Microsoft Office Excel 2003. За тестирање на значајноста во разликите беше користена непараметриска статистика (Pearson c² тест). Сигнификантноста беше одредувана за ниво на p<0.05. |

|

After collecting the data, they were grouped, classified in tables, processed and graphically presented by the program Microsoft Office Excel 2003. To test the significant difference we used non-parameter statistics (Pearson c² test). The significance was determined at level p<0.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

Резултати |

|

Results |

|

|

|

|

|

Повеќето од родителите се изјаснија дека знаат каква попреченост има нивното дете (28 или 90,3%). Дваесет (64,5%) родители тоа го дознале во првата година од животот на нивното дете. Во најголем број од случаите (25 или 80,6%) им било соопштено од страна на лекар. Останатите 6 (19,4%) родители сами откриле дека нивното дете отстапува во развојот. |

|

Most of the parents stated that they are familiar with their child’s disability (28 or 90,3%). 20 (64,5%) parents found it out in the first year of their child’s life. In most of the cases (25 or 80,6%) parents were informed by a doctor. The rest of them, 6 parents (19,4%) found out on their own that there were some kind of obstacles in their child’s development. |

Табела 1/Table 1

|

Професионален однос / Professional relationship |

Интелектуална попреченост / Intellectual disabilities |

Церебрална парализа / Cerebral palsy |

Оштетен вид / Visual impairment |

Вкупно/Total |

||||

|

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

|

|

A |

2,18 |

0,75 |

1,58 |

1,24 |

0,75 |

1,03 |

1,58 |

1,14 |

|

B |

1,72 |

0,90 |

1,83 |

1,11 |

1 |

1,30 |

1,58 |

1,11 |

|

C |

2,09 |

0,94 |

1,50 |

1,16 |

1 |

1,30 |

1,58 |

1,17 |

|

D |

1,63 |

1,02 |

1,83 |

1,26 |

1 |

1,30 |

1,54 |

1,20 |

df=6 p=0.894

A: Поддршка/Support

B: Ви дадоа информации за попреченоста/ They gave you information about the disability

C: Внимателно ги ислушуваа Вашите грижи/ They carefully listened your worries

D: Согласување помеѓу професионалците (за дијагнозата и третманот)/ Coordination among the professionals (for the diagnosis and the treatment)

|

Во табелата 1 се презентирани одговорите на родителите за професионалниот однос на медицинскиот кадар и останатите професионалци инволвирани во раната интервенција на детето. Од истата може да се види дека вкупната средна вредност на одговорите се движи од 1,54+1,20 до 1,58+1,17, односно од многу незадоволително до незадоволително ниво (0 – никаков, 1 – многу незадоволителен, 2 – незадоволителен, 3 – задоволителен, 4 – многу задоволителен). Статистичката значајност p има вредност 0,894, што значи дека не постои статистички значајна разлика во начинот на комуникација на професионалците со родителите на деца со различен вид попреченост. |

|

Table 1 presents the answers of parents about the professional attitude of the medical staff and the other professionals involved in the early stage of the intervention. We can conclude that the total average value of the answers is between 1,54+/-1,20 and 1,58+/-1,17, or starting at a very unsatisfying level and going to an unsatisfying level (0- unsatisfying at all, 1 – very unsatisfying, 2 – unsatisfying, 3 – satisfying, 4 – very satisfying). The statistical difference p has a value of 0,894, which means that there is no statistically significant difference in the manner of communication of the professionals with the parents of children with different types of disabilities. |

Табела 2/Table 2

|

Начин на комуникација/ Way of communication |

N |

% |

|

Експертска: ... направете го тоа и тоа!/ Expert: ... do this and that! |

7 |

22,6 |

|

Информативна: ...направете го тоа, затоа што .../ Informative: ...do that, because of... |

13 |

41,9 |

|

Партнерска: ...можете да го направете тоа или тоа, што Вие мислите?/ Partner:...you can do this or that, what do you think? |

11 |

35,5 |

|

Вкупно/ Total |

31 |

100 |

|

Тринаесет (41,9%) родители се изјасниле дека медицинскиот персонал и останатите професионалци им го соопштиле понатамошниот третман на нивното дете на информативен начин „...направете го тоа, затоа што ...“ (табела 2). |

|

13 (41,9%) parents have stated that the medical staff and other professionals have informed them about the subsequent treatment of their child in an informative way “do that, because ...”(Table 2). |

Табела 3/Table 3

|

Стресни ситуации поврзани со детето со пречки во развојот/ Stressful situations related to the child with developmental disabilities |

Интелектуална попреченост/ Intellectual disabilities |

Церебрална парализа/ Cerebral palsy |

Оштетен вид/ Visual impairment |

Вкупно/Total |

||||

|

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

|

|

A |

3,63 |

0,50 |

3,66 |

0,65 |

3,75 |

0,46 |

3,67 |

0,54 |

|

B |

3,27 |

0,78 |

2,83 |

0,83 |

3,62 |

0,51 |

3,19 |

0,79 |

|

C |

2,27 |

1,34 |

1,91 |

1,31 |

3,50 |

0,53 |

2,45 |

1,31 |

|

D |

2,45 |

1,12 |

2,41 |

1,37 |

3,50 |

0,53 |

2,70 |

1,18 |

|

Е |

2,27 |

1,42 |

2,91 |

1,08 |

3,37 |

0,51 |

2,80 |

1,27 |

|

F |

2,09 |

1,57 |

1,83 |

1,26 |

3,12 |

0,83 |

2,25 |

1,36 |

|

G |

2,90 |

1,30 |

3,50 |

0,90 |

3,87 |

0,35 |

3,38 |

1,02 |

|

Вкупно / Total |

2,72 |

1,24 |

2,72 |

1,24 |

3,53 |

0,57 |

2,93 |

1,16 |

df=12 p=0.936

A: Сознанието за пречките во развојот на детето/ Information about the child with developmental disabilities

B: Да им објасните на другите/ Explaining to the others

C: Секојдневниот контакт со пријателите/соседите/ Everyday contact with friends /neighbors

D: Контактот со медицинскиот персонал/ Contact with the medical staff

E: Контактот со административниот персонал/ Contact with administrative staff

F: Контактот со едукативниот персонал/ Contact with educational staff

G: Справување со финансии/ Managing the financial part

|

Во табелата 3, дадени се одговорите на 7-те прашања од прашалникот FSCI (Family Stress and Coping Interview) (22). Родителите што го рангираa степенот на стрес го доживеале поврзан со детето со пречки во развојот, користејќи ја Петстепената Ликертова скала. (0 – не било стресно, 1 – малку стресно, 2 – стресно, 3 – многу стресно и 4 – екстремно стресно). Од истата може да се види дека повеќето од родителите доживеале голем стрес кога дознале дека нивното дете има пречки во развојот (3,67 +0,54). За нив прилично стресно им било и справувањето со финансиите (3,38 +1,02), а најмалку стресен им бил контактот со едукативниот персонал (2,25 +1,36). Во однос на видот на попреченоста и степенот на стрес кој го доживеале родителите, не постои статистички значајна разлика помеѓу родителите на децата со интелектуална попреченост, церебрална парализа и оштетен вид (p=0,936). |

|

In table 3, there are answers for the 7th question form the FSCI (Family Stress and Coping Interview) (22) questionnaire. The parents rated the degree of the stress that they experienced in relation to the child with developmental disabilities, by using the five degree Likert scale (0 - was not stressful, 1 - little stressful, 2 - stressful, 3 - very stressful, 4 - extremely stressful). From the same Table it can be seen that most of the parents have experienced a huge stress when they found out that their child has developmental disabilities (3,67+/-0,54). One of the most stressful thing for them was coping and managing the financial expenditures (3,38+/-1,02), and less stressful was the cooperation with the educational staff (2,25+/-1,36). Regarding the type of disability and the degree of stress endured by the parents, we can conclude that there is no statistically significant difference between the parents of children with intellectual disability, cerebral palsy and impaired vision (p=0.936). |

Табела 4/Table 4

|

Лица/ Persons |

Интелектуална попреченост/ Intellectual disabilities |

Церебрална парализа/ Cerebral palsy |

Оштетен вид/ Visual impairment |

p |

|||

|

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

АС (М) |

СД (SD) |

||

|

Партнерот/The partner |

2,54 |

0,82 |

2,77 |

0,44 |

2,80 |

0,44 |

0,188 |

|

Моите родители/ My parents |

1,70 |

1,18 |

1,50 |

1,08 |

2,50 |

0,75 |

0,490 |

|

Родителите на мојот сопруг/сопруга/ My spouse’s parents |

2,33 |

0,86 |

1,80 |

1,13 |

2,14 |

1,21 |

0,783 |

|

Потесното семејство браќа/сестри/ Immediate family Brothers/sisters |

1,75 |

1,28 |

1,5 |

1,06 |

2,12 |

1,24 |

0,442 |

|

Поширокото семејство/ Wider family |

1 |

0,70 |

0,87 |

1,12 |

1,42 |

1,27 |

0,294 |

|

Моите пријатели/ My friends |

1,8 |

1,09 |

0,71 |

0,83 |

1,42 |

1,13 |

0,632 |

|

Пријателите на мојот сопруг/сопруга/ My spouse’s friends |

1,2 |

0,44 |

0,62 |

0,74 |

1,28 |

1,38 |

0,380 |

|

Моите деца/ My children |

2,12 |

0,83 |

2,22 |

1,20 |

2,16 |

1,16 |

0,662 |

|

Колеги/ Colleagues |

0,2 |

0,44 |

1,14 |

1,21 |

2,5 |

1 |

0,018 |

|

Социјални групи (здруженија на лица со инвалидност) / Social groups (Associations for persons with disabilities) |

1,66 |

1,21 |

1,33 |

1,11 |

0,2 |

0,44 |

0,019 |

|

Локална заедница Local community |

0,28 |

0,48 |

0,66 |

1,03 |

0 |

0 |

0,161 |

|

Добиените резултати покажаа дека постои статистички значајна разлика во одговорите на родителите со деца со различен вид на инвалидност во однос на одредени ресурси кои ги имаат за помош и поддршка, како што се колегите и социјалните групи, т.е. здруженијата на лицата со инвалидност. Имено, родителите на децата со оштетен вид во однос на родителите на децата со друга попреченост, најголема помош и поддршка добиваат од своите колеги (2,5+1), а најмала од социјалните групи (0,2+0,44). За разлика од нив, родителите на децата со интелектуална попреченост најголема помош и поддршка добиваат од социјалните групи, т.е. здруженијата на лицата со инвалидност (1,66+1,21), а најмала од своите колеги (0,2+0,44). |

|

The obtained results showed that there is statistically significant difference in the answers of the parents of children with different types of disabilities regarding certain resources for help and support that they receive, from their colleagues and other social groups that is from associations of persons with disabilities. The largest help and support that the parents of children with vision impaired receive, in comparison to parents of children with different types of disabilities, is by their colleagues (2,5+1). They receive the lowest help and support by social groups (0,2+0,44). Unlike them, parents of children with intellectual disabilities receive the biggest help and support by the social groups (associations of persons with disabilities (1,66+1,21), and the least from their colleagues (0,2+0,44). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

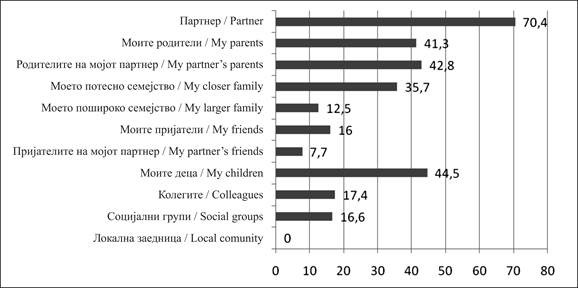

Слика 1: Многу голема помош и поддршка (%) |

|

Figure 1. Biggest help and support (%) |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Од сликата 1 може да се види дека родителите најголема помош и поддршка добиваат од својот брачен другар (70,4%). Како ресурс за помош и поддршка, родителите на децата со пречки во развојот ги посочуваат и бабите и дедовците, како и своите останати деца. |

|

By Table 4 and picture 1 it can be seen that parents receive the biggest help and support from their spouses (70,4%). As a resource for help and support, parents point at grandparents as well as at their children’s siblings. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Дискусија |

|

Discussion |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Семејството е критичен извор на поддршка за децата со пречки во развојот. Начинот како семејството се справува со фактот дека има дете со пречки во развојот, бил фокус на многу истражувања во последните две децении (24, 25). Во нив се опишува како родителите реагираат на детските проблеми во развојот: некои се премногу емоционални, други повлечени и оставаат впечаток дека се незаинтересирани, но има и родители кои реално ја прифаќаат состојбата на нивното дете. Повеќето од истражувањата за родителите на децата со пречки во развојот се правени во англосаксонските земји и малку се знае за ситуацијата на родителите во други културни контексти. Оваа студија беше спроведена во Македонија, земја со слабо развиена рана поддршка од мултидисциплинарни тимови на семејствата со децата со пречки во развојот. Соодветните информации и совети за попреченоста на детето се многу важни детерминанти за родителското справување со стресната ситуација (26). Многу родители кои имаат деца со пречки во развојот зборуваат и пишуваат со горчина за тоа како кон нив се однесувале професионалците. Од нашето истражување, исто така може да се заклучи дека родителите не се задоволни од професионалците, односно од: нивната поддршка, информациите кои ги добиваат, разбирањето и согласувањата помеѓу професионалците во однос на дијагнозата и понатамошниот третман на детето. Според Appleton и Minchom постојат 3 начина на комуникација помеѓу родителите и професионалците, и тоа: експертска, информативна и партнерска (27). Во ова истражување само 11 (35,5%) родители се изјасниле дека медицинскиот персонал и другите професионалци го користеле партнерскиот начин на комуникација кој е и најдобар, односно понатамошниот третман на нивното дете им бил предложен на начин „... можете да го направите тоа или тоа, што мислите Вие?“ Во истражувањето на Jones и Passey во 2005 година, 82,4% од 48 анкетирани родители доживеале екстремен стрес при контакт со докторите (3,49+1,24). 55,6% од нив најголема поддршка добиле од своите партнери, а само 20% од нивните родители (28). Во нашиот примерок, значително помал процент (32,3%) од родителите се изјасниле дека доживеале екстремен стрес при контакт со медицинските професионалци. На прво место по интензитет на стрес за нив било сознанието дека нивното дете е со пречки во развојот (3,67+0,54). Семејната кохезија и чувството на заедништво и соработка е втората детерминанта која, исто така, е многу важна за справување на родителите со стресните ситуации поврзани со нивното дете со пречки во развојот. Бројни студии за родителите на деца со пречки во развојот укажуват на постоењето на поврзаност помеѓу социјалната поддршка и родителскиот стрес (29, 30), односно повисоките нивоа на поддршка кореспондираат со пониски нивоа на родителски стрес. Во однос на поддршката, во нашето истражување најголем процент (70,4%) од родителите се изјасниле дека имале најголема поддршка од своите партнери, а од локалната заедница 13,6% се изјасниле дека имаат повремена и 9,1% голема поддршка. |

|

The family is a critical source of support for the children with developmental disabilities. The way in which the family deals with the fact that they have a child with developmental disabilities was the focus of many researches in the last two decades (24, 25). They all describe parents’ reactions to the child’s developmental problems: some of them are too emotional, others are quiet and seem uninterested, but there are also parents who accept the reality about their child.

Most of the research studies for parents of the children with developmental disabilities were conducted in Anglo-Saxon countries, and little is known about the situation of the parents in other cultural contexts. This study was conducted in the According to Appleon and Minchom there are three ways of communication between parents and professionals: an expert, informative and partner communication (27). In this research only 11 (35,5%) parents stated that the medical staff and other professionals used the partner the way of communication which is also considered as the best one, meaning that the following treatment of their child was suggested in this way “…you can do this or that, what do you think?” In Jones and Passy’s research in 2005- 82.4% out of 48 examined parents experienced an extreme stress when contacting the doctors (3.49+/-1.24). 55.6% of them received the biggest support by their partners, and only 20% by their parents (28). In our sample, a significantly smaller percent (32.3%) of the parents stated that they experienced an extreme stress when contacting the medical professionals. According to the stress level, finding out that their child has developmental abilities is in the first place (3.67 +0.54). The family cohesion and the feeling of belonging to the community and cooperation are the second determinants which are also very important for parental dealing with the stressful situations related to their child with developmental disabilities. Numerous studies for parents of children with developmental disabilities suggest that there is a relation between the social support and the parental stress (29, 30), pointing out that higher levels of support correspond with the lower levels of parental stress. In terms of support, in our research, the greatest percentage (70.4%) of the parents answered that they received the biggest support by their partners, however none stated that there was a big support by the local community. From the local community, only 13.6% got occasional support and 9.1% got big support. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Заклучок |

|

Conclusion |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Службите за помош и поддршка треба да се фокусираат на потребите на целото семејство, а не само на проблемите на детето со пречки во развојот. Во споредба со минатото, родителите не се само пасивни набљудувачи на рехабилитацијата и едукацијата, туку активни и рамноправни членови и учесници. Многу истражувања го посочуваат неповолното влијание на „хендикепираниот“ член во семејството врз животот на целото семејство. Во некои од нив се истакнува дека „хендикепираното“ дете всушност значи и „хендикепирано“ семејство (31). Но има и истражувања кои потенцираат дека иако родителите на децата со пречки во развојот доживуваат голем стрес, тие исто така доживуваат и задоволство при секој најмал успех на нивното дете. Овие родители сметаат дека нивното дете има посебни потреби, а не проблеми (32−35). Родителите на децата со пречки во развојот имаат посебни потреби – потреба за информации, совети, поддршка и практична помош, како и потреба да бидат вклучени во секоја фаза на идентификација и проценка на нивното дете (DfES, 2001). За да се остварат овие потреби, треба да се комбинираат формални и неформални социјални мрежи за поддршка и адаптација (36). Неформалната поддршка може да има „тампон“ ефект на стресот (37). Резултатите од нашето истражување покажуваат дека родителите на децата со пречки во развојот доживеале високо ниво на стрес, особено кога дознале дека нивното дете има пречки во развојот. Ова истражување има голем број ограничувања. Малиот примерок секако дека не може да придонесе за генерализирање на добиените резултати. Идните истражувања во нашата држава треба да бидат насочени и кон придобивките од раната интервенција, едукацијата на родителите и користењето на служби за поддршка на родителите на деца со пречки во развојот. |

|

Institutions for help and support should focus on the needs of the entire family, and not only on the needs of the child with developmental disabilities. In comparison to the past, parents are not just passive observers of the rehabilitation and the education, but they are active and equal members and participants. A lot of researches point to the unwanted influence of the “handicapped” member in the family. Some of them emphasize that a “handicapped” child actually means a “handicapped” family (31). However, there are researchers that emphasize that although parents of children with developmental disabilities experience big stress, they also experience an immense happiness with every success of their child. These parents consider that their child has special needs and not problems (32−35). The parents of the children with developmental disabilities have special needs - need for information, advice, support and practical help, and need for their inclusion in every phase of identification and assessment of their child (DfES, 2001). For accomplishment of these needs, it is necessary to combine the formal and informal social networks for support and adaptation (36). The informal support can diminish or moderate the effect of stress (37). The services for help and support should be focused on the needs of all family members, and not only on the problems of the child with developmental disabilities. The results from our research show that parents of children with developmental disabilities experienced a high level of stress, especially when they discovered that their child has developmental disabilities. This research has a number of limitations; the small sample cannot contribute to the generalization of the obtained results. The future research in our country should be directed towards the benefits of early intervention, education of the parents and usage of the services for support of the parents of children with developmental disabilities. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Citation: Chichevska Jovanova N, Dimitrova Radojichikj D. Parents of Children with Developmental Disabilities: Stress and Support. J Spec Educ Rehab 2013; 14(1-2):7-19. doi: 10.2478/v10215-011-0029-z |

||||

|

Article Level Metrics |

||||

|

Литература / References |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

Share Us

Journal metrics

-

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 -

IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 -

SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 -

h5-index 7

h5-index 7 -

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

10 Most Read Articles

- PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE / REJECTION AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS WITH AND WITHOUT DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

- RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFE BUILDING SKILLS AND SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT OF STUDENTS WITH HEARING IMPAIRMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR COUNSELING

- EXPERIENCES FROM THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM – NARRATIVES OF PARENTS WITH CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN CROATIA

- INOVATIONS IN THERAPY OF AUTISM

- AUTISM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

- DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDERS – AN OVERVIEW

- THE DURATION AND PHASES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- REHABILITATION OF PERSONS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY

- DISORDERED ATTENTION AS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL COGNITIVE DISFUNCTION

- HYPERACTIVE CHILD`S DISTURBED ATTENTION AS THE MOST COMMON CAUSE FOR LIGHT FORMS OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY