JSER Policies

JSER Online

JSER Data

Frequency: quarterly

ISSN: 1409-6099 (Print)

ISSN: 1857-663X (Online)

Authors Info

- Read: 48201

|

МЕРЕЊЕ НА САМОПОЧИТТА КАЈ ГЛУВИТЕ/НАГЛУВИТЕ СТУДЕНТИ

Јин ЖЕНГ

Институт за образовни науки, Редовен универзитет Џенгџоу, Кина Оддел за психологија, Национален универзитет Гјеонгсанг, Кореја |

|

MEASURING SELF-ESTEEM OF DEAF/HARD OF HEARING COLLEGE STUDENTS

Jin ZHENG

Institute of Educational Science, Zhengzhou Normal University, China. Department of Psychology, Gyeongsang National University, Korea. |

|

Примено: 13.09.2012 Прифатено: 21.11.2012 UDK: 159.923.2-056.263-057.87(519)

|

|

Recived: 13.09.2012 Accepted: 21.11.2012 Original Article |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Вовед |

|

Introduction |

|

|

|

|

|

Глувите/наглувите лица се соочуваат со некои предизвици зашто луѓето што слушаат тешко можат да ги разберат. Неколкумина научници забележуваат дека појавата на низок степен на самопочитување е повисока меѓу глувите/наглувите лица отколку меѓу луѓето што слушаат (1, 2). Многу истражувања се обиделе да го испитаат овој комплексен феномен за подобро да се разбере како влијае глувоста на самопочитувањето (1, 3). Mulcahy (4) идентификува неколку потенцијални социјални фактори што можат да влијаат на самопочитувањето кај глувите лица: слаба комуникација со родителите, неадекватно поврзување со мајката, чувство на недоверба поради чувство на нерамноправност и поради негативните ставови кон глувите луѓе, слабо стекнување на вештината за употреба на знаковниот јазик (ЗЈ), недостаток на соодветни примери за имитирање, општествена изолација, негативна претстава за телото, недостаток на силен културен идентитет и отфрлање од членовите на семејството и од општеството воопшто. Овие сознанија се поддржани и со други истражувања (1, 2). Самопочитувањето кај глувите лица е поврзано со евалуацијата на социјалните фактори или со колективната самопочит (како што е спомнато погоре). Сепак, нивото на стигматизација на една личност во општеството не влијае на индивидуалното самопочитување, a односот меѓу самопочитувањето и фаворизирањето во група, е нејасен (5). Имплицитното самопочитување се однесува на способноста на една личност да се оцени себеси на еден спонтан, автоматски или несвесен начин, спротивно на експлицитното самопочитување кое опфаќа посвесна и мисловна самоевалуација. Самопочитувањето вклучува имплицитни и експлицитни фактори. Кога станува збор за самопочитувањето, се забележува дека веродостојноста и валидноста на некои имплицитни мерки се вознемирувачки. Bosson и др. (6) го испитувале односот меѓу седум имплицитни мерки на самопочитувањето, четири експлицитни мерки на самопочитувањето и неколку варијабли за коишто се предвидува дека корелираат со мерките за самопочитување. Тестирањето-ретестирањето на веродостојноста на мерките за имплицитното самопочитување покажа одлична варијабилност, со тоа што само две од мерките за имплицитно самопочитување покажуваа прифатливо ниво на веродостојност: тест за имплицитна асоцијација (ТИА) за почитувањето и задачата за евалуација - преферирање на сопствените иницијали (name-letter task). Веродостојноста на мерките за имплицитно самопочитување беше ревидирана и беше истражена целата конзистентност и повремената стабилност на различните мерки за имплицитно самопочитување (7). Испитаниците (N=101) одговорија двапати - со временско задоцнување од 4 недели на пет различни задачи: тестот на имплицитна асоцијација (ТИА), скратениот тест на имплицитна асоцијација (BIAT - Brief Implicit Association Test), задачата за афективна подготовка (APT - Affective Priming Task), Симоновата задача за надворешното влијание на идентификацијата (ID-EAST - the Identification-Extrinsic Affective Simon Task) и задачата за преферирање на иницијалите (NLT - Name-Letter Task). Тестот на имплицитна асоцијација за самопочитување доби највисок коефициент на веродостојност. За да им се помогне на глувите/наглувите студенти подобро да се интегрираат во општеството, треба да се обрне големо внимание на развојните карактеристики на нивната самопочит, кои се непосредно поврзани со нивната социјална интеракција. Сепак, досега е извршено само рудиментирано истражување на имплицитното самопочитување на глувите/наглувите студенти; теоретската анализа сѐ уште не е завршена на ниво што задоволува. За ова истражување глувите/наглувите студенти беа избрани да ги истражат карактеристиките на нивното самопочитување. Генерално, ниската самопочит е тесно поврзана со депресијата. Корелацијата меѓу депресијата и имплицитната самопочит на глувите/наглувите студенти на факултет е објаснета подолу. |

|

Deaf/hard of hearing individuals face some challenges that the hearing world may find difficult to understand. Several scholars notice that the incidence of low self-esteem is higher among Deaf/hard of hearing individuals than among hearing individuals (1, 2). Many studies tried to examine this complex phenomenon for a better understanding of how deafness influences self-esteem (1, 3). Mulcahy (4) identifies some potential social factors that may influence a deaf individual’s self-esteem: poor parental communication skills, inadequate maternal bonding, feelings of mistrust due to a sense of inequality and negative attitudes toward deaf people, poor acquisition of sign language (SL) skills, lack of appropriate role models, social isolation, negative body images, lack of a strong cultural identity, and rejection from the family members and the society in general. These findings are supported by other studies (1, 2). The deaf individual’s self-esteem is correlated with evaluations of social factors or collective self-esteem (as mentioned above). However, the stigmatization level of one's social identity has no effect on personal self-esteem, and the relationship between self-esteem and in-group favoritism is unclear (5). Implicit self-esteem refers to a person's disposition to evaluate himself or herself in a spontaneous, automatic, or unconscious manner. It contrasts with explicit self-esteem, which entails more conscious and reflective self-evaluation. Self-esteem includes explicit and implicit factors. In the self-esteem domain, the reliability and validity of some implicit measures of self-esteem are found disturbing. Bosson et al. (6) investigated the relationship between seven implicit measures of self-esteem, four explicit measures of self-esteem, and several variables predicted to correlate with measures of self-esteem. The test-retest reliabilities of implicit self-esteem measures showed great variability, with only two of the implicit self-esteem measures showing reliably acceptable levels: the esteem Implicit Association Test (IAT) and the name-letter evaluation task. Reliability of implicit self-esteem measures was revisited and the internal consistencies and temporal stabilities of different implicit self-esteem measures (7) were investigated. Participants (N = 101) responded twice - with a time lag of 4 weeks - to five different tasks: the Implicit Association Test (IAT), the Brief Implicit Association Test (BIAT), the Affective Priming Task (APT), the Identification-Extrinsic Affective Simon Task (ID-EAST) and the Name-Letter Task (NLT). Self-esteem IAT got the highest reliability coefficients. To help the Deaf/hard of hearing students to integrate better into society, one should pay greater attention to the development characteristics of their self-esteem which are closely related to their social interaction. However, there has only been rudimentary research on the implicit self-esteem of the Deaf/hard of hearing students; the theoretical analysis has still not been completed satisfactorily. For this study, Deaf/hard of hearing students were selected to explore the characteristics of their self-esteem. In general, low self-esteem is closely related to depression. The correlation between depression and implicit self-esteem of Deaf/hard of hearing college students is further discussed below. |

|

|

|

|

|

Методологија на истражувањето |

|

Method |

|

|

|

|

|

Субјект |

|

Subject |

|

Испитаниците во ова истражување беа избрани од почетниот курс за култура на Одделот за специјална едукација при Редовниот универзитет Џенгџоу. Добиен е примерок од 36 испитаници (19 женски, 17 машки), со просечно губење на слухот од 68 dB. Сите испитаници беа на возраст од (± СД) 19.4 (±0.9) и без какви било познати психолошки проблеми. Сите се опишаа себеси како глуви или наглуви и тврдеа дека можат течно да комуницираат употребувајќи го кинескиот знаковен јазик. Тројца беа исклучени зашто не ги следеа инструкциите. |

|

Participants for this study were recruited from an introductory culture course at the Department of Special Education of Zhengzhou Normal University. A sample of 36 participants (19 female, 17 male), with an average hearing loss of 68 dB, was obtained. All the participants were aged (± SD) 19.4 (±0.9) and were free of any known psychological problems. They all identified themselves as Deaf or hard of hearing, and claimed they can communicate fluently using Chinese Sign Language. Three were excluded because they did not follow instructions. |

|

|

|

|

|

Материјал |

|

Material |

|

Имплицитен тест: самоопишувачки, и несамоопишувачки, беа употребувани зборови за концепти, атрибутивни зборови (на пр.: паметен, грд) и афективни зборови (на пр.: мир, отров) како елементи на позитивни или негативни атрибути. Сите зборови, презентирани во кинеска форма, беа избрани според критериумот на Greenwald и Farnham (8). Експлицитни мерки за самопочитување: испитаниците понатаму ја завршија верзијата лист и молив од експлицитните мерки за самопочитување: семантички диференцијал за себе, термометар на чувствата за себе и Росенберговата скала за самопочитување (1965). При семантичкиот диференцијал, испитаниците се оценуваат себеси во однос на пет биполарни димензии: лош/добар, непријатен/пријатен, грд/убав, глупав/паметен и грозен/прекрасен. Секоја димензија беше оценета на скала од седум точки, почнувајќи од -3 (негативно) до +3 (позитивно). Термометарот на чувствата за себе беше составен од единствена точка на којашто испитаниците се оценуваа себеси рангирајќи од 0 (неповолно) до 100 (поволно). За Росенберговата скала за самопочитување, испитаниците одговараа на секоја точка на Ликертовата скала од 7 точки, рангирајќи од 1 (апсолутно несогласување) до 7 (апсолутно согласување). Ниво на нивната депресија: испитаниците исто така ја извршија експлицитната мерка на депресија инструментот - Скала за саморангирање на депресијата (SDS - The Self-rating Depression Scale). ССД е широко употребуван прашалник за самопријавување на психолошко нарушување и депресија; исто така, се употребува како дел од оценувањето хронична болка на пациенти и кај друга непсихијатриска популација. Поради преведувачките бариери, се употребуваат повеќе верзии на овој прашалник, а некаде некои од опциите не можат соодветно да се преведат, што резултира со девијации во резултатите од тестот. За прикладност на тестирањето, овој експеримент употребува популарни и квантитативни изрази (SDS-R) и метод на остварување поени на суптилен начин за да се намалат грешките. Исто така, беше обезбеден преведувачки сервис за кинескиот знаковен јазик за делумно да им се олесни на испитаниците разбирањето на содржината на прашалникот. |

|

Implicit Test: Self-descriptive, and not-self-descriptive words were used for the concepts, attributive words (e.g., smart, ugly) and affective words (e.g., peace, poison) as items for positive and negative attributes. All words, presented in Chinese form, were selected from the criterion of Greenwald and Farnham (8). Explicit Measures of Self-esteem: the next participants completed paper-and-pencil versions of the explicit measures of self-esteem: a self-semantic differential, a self-feeling thermometer, and the Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale. In the semantic differential, the participants rated themselves in terms of five bipolar dimensions: bad/good, unpleasant/pleasant, ugly/beautiful, foolish/ wise, and awful/nice. Each dimension was rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from –3 (negative) to +3 (positive). The self-feeling thermometer consisted of a single item on which the participants rated themselves ranging from 0 (unfavorable) to 100 (favorable). For the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the participants responded to each item on a 7-point Likert-type Scale, ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). Level of Their Depression: The participants also completed the explicit measure of depression: The Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) instrument. The SDS is a widely-used questionnaire for self-reporting of psychological distress and depression; it is also used as part of the evaluation of chronic pain patients and other non-psychiatric populations. Owing to translation barriers, multiple versions of this questionnaire have been in use where some of the options could not be translated appropriately, resulting in the deviation of test results. For convenience of the testing, this experiment used a more popular and quantified expression (SDS-R) and the method of subtle points to reduce error. Also, Chinese Sign Language–translated service was provided partially to facilitate the participants understand the content of the questionnaire. |

|

|

|

|

|

Процедура |

|

Procedure |

|

Измерено беше експлицитното самопочитување на секој испитаник. На сите испитаници им беа дадени прашалници што требаше самостојно да ги пополнат на самото место. Исто така, секој испитаник беше подложен на имплицитен тест, следејќи ги стандардите на IAT-процедурите, засновани на стандардите на IAT-парадигмата (9) со минимални модификации (табела 1). Инструкциите на испитаниците им беа дадени на кинескиот знаковен јазик за да им се олесни разбирањето на IAT-процедурата. |

|

The explicit self-esteem of each subject was measured. All the participants were given the questionnaire forms to be completed independently on the spot. Also, each participant was subjected to IMPLICIT test following the standard IAT procedures, based on the standard IAT paradigm (9) with minor modifications (Table 1). Instructions to the participants were given in Chinese Sign Language to facilitate their understanding of the IAT procedure. |

|

|

|

|

|

Табела 1 Процедурата јас - другите од IAT |

|

Table 1. Procedure of the Self-Other-IAT |

|

Блок */ Block * |

Функција/ Function |

Лево копче/ Left key |

Десно копче/ Right key |

|

1 |

Вежба/Practice |

Зборови со позитивна конотација (a)/ Positive trait words (a) |

Зборови со негативна конотација (b)/ Negative trait words (b) |

|

2 |

Вежба/Practice |

Самоопишувачки зборови (a1)/ Self-descriptive words (a1) |

Несамоопишувачки зборови (b1)/ Not-self-descriptive words (b1) |

|

3 |

Вежба/Practice |

a+a1 |

b+b1 |

|

4 |

Тест/Test |

a+a1 |

b+b1 |

|

5 |

Вежба/Practice |

b1 |

a1 |

|

6 |

Вежба/Practice |

a+b1 |

b+a1 |

|

7 |

Тест/Test |

a+b1 |

b+a1 |

* Нема пауза меѓу блокот 3 и 4 и меѓу 6 и 7.

* No break between block 3 and 4 and between block 6 and 7.

|

Резултати и дискусија |

|

Results and Discussion |

|

|

|

|

|

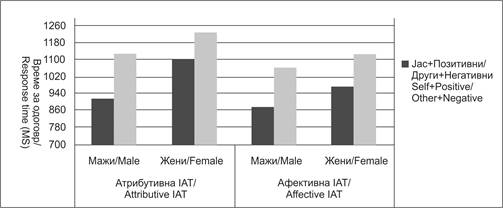

Податоците од петтемина испитаници со степен на грешка повисок од 20% на IAT беа отфрлени. IAT-податоците за анализа се добиени само од собирањето на пробните податоци од блоковите 4 и 7 (табела 1). Беше следена стандардната процедура за анализирање на IAT-податоците (9). Времето на одговор помало од 300 беше рекодирано на 300 мс, а ако е подолго од 3000 беше рекодирано на 3000 мс. Времето на одговор беше лог-трансформирано и за сите одговори од секој блок беше определен просек. IAT-резултатот беше добиен со одземање на просечното време на одговор во блок 4 од просечното време на одговор во блок 7. Позитивните резултати укажуваат на позитивни асоцијации за себе (и/или негативни асоцијации за другите), потоа негативни асоцијации за себе (и/или позитивни асоцијации за другите). Првичната анализа ги испитува ефектите на два последователни IAT и два последователни блока на ефектите на IAT. Ниту варијаблите за противтежа немаат значаен ефект. Испитаниците побрзо одговараат кога се поврзуваат со позитивни елементи (слика 1). IAT-мерката за самопочитување покажа позитивни резултати на почитување за двата: атрибутивен IAT, според Cohen d = 1.76, F (1, 24) = 42.64, p < 0.0001, и афективниот IAT, според Cohen d = 1.07, F (1, 24) = 15.87, p < 0.0001. Просечните ефекти на IAT од атрибутивните и афективните мерки, не се значајно различни F (1, 24) = 0.16, p =0.69. Се покажа дека машките испитаници имаат повисок степен на самопочитување од женските. Имаше статистички значаен ефект во поглед на полот при атрибутивниот IAT, t (26) = 2.37, p< 0.05. Полот ги ублажи ефектите на афективниот IAT, така што машките испитаници покажуваа повисоко имплицитно самопочитување од женските. Во табелата 2 се прикажани средните вредности на три експлицитни мерки на самопочитувањето, класифицирани според полот. Ефектот на полот не беше значаен. Експлицитните мерки не корелираа значајно со ниедна од IAT-мерките на самопочитувањето, просечно r = –0.17. Во овие податоци не постои евиденција за корелација меѓу мерките на SDS-R и атрибутивниот (r = 0.29) или афективниот IAT (r = 0.22). |

|

The data from five participants with error rates greater than 20% on IAT were discarded. IAT data for analyses were obtained only from the trial-data collection block 4 and 7 (Table 1). The standard procedure for analyzing IAT data was followed (9). Response times smaller than 300 were recoded to be 300 ms, and responses larger than 3000 were recoded to be 3000 ms. Response times were log-transformed, and all responses within each block were averaged. An IAT score was obtained by subtracting the average Block 4 response time from the average Block 7 response time. Positive scores indicate greater positive associations with self (and/or negative associations with other) than negative associations with self (and/or positive associations with other). Initial analysis examined the effects of order of the two IATs and order of the two critical blocks on IAT effects. Neither counterbalancing variable had a significant effect. Subjects responded much more rapidly when associating self with positive items (Figure 1). IAT self-esteem measures revealed positive esteem scores for both the Attributive IAT, Cohen's d = 1.76, F (1, 24) = 42.64, p < 0.0001, and the Affective IAT, Cohen's d = 1.07, F (1, 24) = 15.87, p < 0.0001. The mean IAT effects for the attributive and affective measures did not significantly differ, F (1, 24) = 0.16, p =0. 69. Males were found to have higher esteem scores than females. There was a statistically significant effect of gender on the Attributive IAT, t (26) = 2.37, p< 0.05. Gender had moderate effects on Affective IAT, such that males tended to report higher implicit self-esteem than females. Means for the three explicit measures of self-esteem are given in Table 2, classified by gender. The effect of gender was not significant. The explicit measures of self-esteem failed to correlate significantly with any of the IAT measures of self-esteem, average r = –0.17. In these data, there was no evidence for a correlation between the measures of SDS-R and either the Attributive IAT (r = 0.29) or the Affective (r = 0.22). |

|

|

|

|

|

Табела 2 Три експлицитни мерки класифицирани според полот |

|

Table 2. Three explicit Measures Classified by Sex |

|

|

Машки/Male |

Женски/Female |

|

Росенбергов SES a/ Rosenberg SES a |

||

|

M± SD |

4.85±0.62 |

4.79±0.53 |

|

Семантички диференцијалb/ Semantic differentialb |

||

|

Средна вредност ± СД / Mean±SD |

0.61±0.98 |

0.46±0.65 |

|

Термометарc /Thermometerc |

||

|

Средна вредност ± СД / Mean±SD |

70.71±11.05 |

71.79±7.98 |

Забелешка: Вкупно N = 28. Мерки: Росенбергов SES, 1-7; Семантички диференцијал за себе, -3-+3; Термометар, 0-99; ефекти на полот: pa = .77; pb = .62; pc = .77.

Note: Total N = 28. Ranges of measures: Rosenberg SES, 1-7; Self-Semantic differential, -3-+3; Thermometer, 0-99; gender effects: pa = .77; pb = .62; pc = .77.

|

Слика 1. Време на одговор за критичните блокови на два теста за имплицитна асоцијација. |

|

Figure 1. Response times for critical blocks for the two Implicit Association Tests (IATs) . |

Забелешка: Времето на IAT не беше лог-трансформирано, така што тоа е прикажано на оригиналната скала. N =28.

Note: IAT times have not been log-transformed so that they are presented on the original scale. N =28.

|

Стандардната интерпретација на IAT за почитта ја прикажува асоцијацијата што ја има единката за себе. Доколку личноста има многу позитивни асоцијации и неколку негативни за себе, тогаш јас + позитивни или пријатни задачи ќе биде многу лесно и времето на одговор на овие испитувања би требало да биде брзо. Наспроти тоа, јас + негативни или непријатни задачи ќе биде многу потешко и времето на одговор за ова испитување би требало да биде бавно. Како резултат, испитаниците со доминирачка позитивна асоцијација за себе ќе имаат позитивен резултат на IAT за почитувањето. Резултатите покажуваат дека имплицитното самопочитување кај глувите/наглувите студенти е позитивно. Врската меѓу поимот јас и зборовите за позитивна евалуација е блиска; со други зборови, ставот кон себе, автоматски активиран со поимот јас, е позитивен и потврден. Неколкумина истражувачи (8, 19) покажуваат дека луѓето („глуви/наглуви“ во ова истражување) имаат значаен ефект на имплицитното самопочитување и сугерираат дека моделите со одделни имплицитни и експлицитни фактори се посупериорни од моделите со единствен фактор. Со други зборови, имплицитното и експлицитното самопочитување имаат различни конструкции. Резултатот од ова истражување исто така посочува дека не постои значајна врска меѓу имплицитното самопочитување и експлицитното самопочитување кај глувите/наглувите студенти. Несомнено, бројот на примерокот за испитување е мал (N = 36), ниската корелација што се добива овде меѓу експлицитните и имплицитните мерки укажува на нивната добра дискриминација на валидноста и дека мерките се со различна конструкција. Резултатите засновани на поголем број испитаници, исто така, укажуваат дека имплицитното самопочитување и експлицитното самопочитување се различни конструкции (r = -0.17, N=145, во истражувањето на Greenwald и Farnham). Резултатите од анализата на два потврдувачки фактора постојано води кон тоа имплицитното и експлицитното самопочитување да се интерпретираат како различни конструкции. Генерално, одвојувањето на имплицитното самопочитување од експлицитното самопочитување е релевантно за психолошкото здравје и за бихевијоралните проблеми. Примената на повеќе признанија, љубезност и грижа, помалку груби казни во образовниот модел има големо значење за конзистентноста на имплицитното и експлицитното самопочитување кај глувите/наглувите студенти. |

|

The standard interpretation of the esteem-IAT is that it measures the associations one has with the self. If a person has many positive associations and few negative associations with self, then self + positive or pleasant tasks will be very easy and response times to these trials ought to be fast. Likewise, self + negative or unpleasant tasks will be more difficult and response times to this stage ought to be slow. As a result, participants with predominantly positive self associations will have a positive score on the esteem-IAT. The results show that implicit self-esteem of Deaf/hard of hearing students is positive. The relationship between self-term and positive evaluation words is close; in other words, self-attitude, automatically activated by self-term, is positive and affirmative. Several researchers (8, 19) demonstrated that people (“Deaf/hard of hearing students” in this study) have significant implicit self-esteem effect and suggest that models with separate implicit and explicit factors are superior to single-factor models. In other words, implicit and explicit self-esteem are distinct constructs. The results of this study also indicate that there is no significant relationship between the implicit self-esteem and explicit self-esteem of Deaf/hard of hearing students. Admittedly, the sample size in this study is small (N=36), the low correlation obtained here between explicit and implicit measures indicates their good discriminant validity, and that the measures are distinct constructs. Results based on a larger sample size also indicate that implicit self-esteem and explicit self-esteem are distinct constructs (r = -0.17, N=145, in Greenwald and Farnham’s study). The results of two confirmatory factor analyses consistently led to interpreting implicit and explicit self-esteem as distinct constructs. Generally speaking, the separation of implicit self-esteem from explicit self-esteem is relevant to psychological health and behavioral problem, more recognition, kindness and concern with less severe punishment in educational mode, has vast importance to the consistence of implicit and explicit self-esteem of Deaf/hard of hearing students. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Општа дискусија |

|

General Discussion |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Изненадувачки, кај IAT-мерките на самопочитување, резултатите се повисоки за машките отколку за женските испитаници, но нема значајна разлика во експлицитните мерки. Овие резултати се различни од претходните истражувања на почитувањето со IAT во тоа што немаше значајна разлика меѓу резултатите од IAT за почитувањето за машките и женските испитаници кои слушаат (6, 8, 9). Понатаму, резултатите од IAT за почитувањето беа незначително повисоки за женските отколку за машките испитаници (10). Можно објаснување за ефектите на имплицитното, но не и експлицитното самопочитување е дека експлицитното самопочитување кај глувите/наглувите студенти секогаш е оштетено од социјалното влијание на споредбите и од негативната евалуација и односот на другите. Сепак, постои позитивна карактеризација на ставот кон себе во нивната автопретстава. Ова најверојатно е затоа што личностите имаат јасни повратни слики од детството, исто како што 5-месечно бебе секогаш претпочита насмеано наместо сериозно лице (11). Ова укажува дека луѓето се раѓаат со позитивна и потврдна самоориентација, која постои во раната адолесценција сѐ до 13-тата година. По 13-тата година, самоевалуацијата започнува постепено да слабее како резултат на криза на сопствениот идентетитет (12, 13). Во текот на овој период, позитивното јас, формирано во раното детство, станува автоматско и интернализирано во претставата за себе поради прекумерна практика. Според тоа, иако тенденцијата на индивидуата за самоафирмација не е свесно очигледна како резултат на растењето, сепак се рефлектира на еден автоматски, несвесен и имплицитен начин, којшто покажува многу имплицитни феномени за самопочитувањето. Затоа, процесот на формирање позитивна самоевалуација кај глувите/наглувите студенти кој започнува во детството, постепено се интернализира во нивната претстава за себе по пубертетот, и така влијае на нивното однесување. Резултатите исто така ги откриваат разликите според полот кај глувите/наглувите студенти при имплицитното самопочитување. Релевантни истражувања сугерираат дека личните особини на глувите/наглувите студенти исто така се различни во однос на полот (14, 15). Според овие истражувања, повеќето машки се екстровертни и авантуристи, додека повеќето женски се интровертни и анксиозни со нестабилни емоции (16). Овие разлики во личните особини можат да влијаат на нивната експлицитна самоевалуација. Особините на личноста на машките се релативно постабилни; по долгорочно искуство, оваа експлицитна самоевалуација постепено и незабележливо ќе влијае на нивната имплицитна самоевалуација. Затоа имплицитното самопочитување на глувите/наглуви машки е различна од слично поставените женски. Згора на тоа, логичен заклучок е дека креирањето инфериорно, имплицитно самопочитување кај женските се должи на наметнатите ограничувања на нејзината улога во кинеското општество, како и на ослабените комуникациски вештини. Од друга страна, и покрај ослабените комуникациски вештини кај машкото, неговата иницијатива, решителноста и социјалната супериорност му даваат посилно имплицитно самопочитување. Greenberg и сор. (17) велат дека самопочитувањето е продукт на индивидуалната адаптација во културната средина, која има ублажувачки ефект на анксиозноста. Генерално, личноста со повисока самопочит покажува подобар статус на менталното здравје. Многу истражувања покажуваат дека не е тесна врската меѓу имплицитното самопочитување и експлицитното самопочитување, така што некои генерално претпочитаат да веруваат дека имплицитното самопочитување и експлицитното самопочитување се независни, што е во согласност со механизмот на двоен однос. Исто така, многу истражувања доаѓаат до заклучок дека е поверојатно на имплицитното самопочитување да влијаат надворешни фактори, а имплицитното и експлицитното самопочитување предвидуваат дискретно бихевијорално изразување на индивидуите. На пример, истражувачите доаѓаат до заклучок дека имплицитното самопочитување не е поврзано со нивото на анксиозност пријавено од страна на индивидуите, туку дека на анксиозниот статус влијае невербалното однесување (18). Слично, авторите не наоѓаат корелација меѓу мерењата со SDS-R и со IAT, што значи дека индексот од IAT не е поврзан со резултатот од SDS-R. Ова сугерира дека односот меѓу нивото на имплицитно самопочитување и депресијата кај глувите/наглувите лица не е значајно. |

|

Surprisingly, on IAT measures of self-esteem, scores are higher for males than for females, but there are no significant differences in explicit measures. This result differs from that of previous esteem-IAT research in that there was no significant difference between esteem-IAT scores for hearing males and females (6, 8, 9). Further, the esteem-IAT scores were marginally higher for women than for men (10). A possible explanation for the effect on implicit, but not explicit self-esteem, is that the explicit self-esteem of Deaf/hard of hearing students is always damaged by social comparison influence and the negative evaluations and attitudes of others. However, there were still positive self-attitude characterizations in their self-schema. This is probably because individual subjects have clear preferences to active feedback since childhood, just like a 5-month-old infant always prefers a smiling face rather than a non-smiling face (11). This indicates that humans are born with positive and affirmative self-orientation, which persists into early adolescence until they are 13 years old. After the age of 13, self-evaluation begins to weaken gradually as a result of self-identity crisis (12, 13). During this period, the positive self, formed in early childhood, becomes automatic and internalized into a self-schema because of excessive practice. This, although the individual tendency of self-affirmation is not obvious in consciousness as a result of aging, is still reflected in an automatic, unconscious and implicit way, which shows many implicit self-esteem phenomena. Therefore, the formation process of positive self-evaluation in the Deaf/hard of hearing students, which commences in childhood, gradually internalizes into their self-schema after puberty, and this affects their behavior. The results also reveal gender differences in Deaf/hard of hearing students’ implicit self-esteem. Relevant studies suggest that the Deaf/hard of hearing students’ personality traits have gender differences as well (14, 15). According to these studies, most of the males are outgoing and adventurous, while most of the females are introvert and anxious with unstable emotions (16). These personality traits differences may impact their explicit self-evaluation. Male personality traits are relatively stable; after a long-term experience, this explicit self-evaluation will gradually and imperceptibly impact their implicit self-evaluation. Therefore, the implicit self-esteem of Deaf/hard of hearing males is different from that of similarly placed females. Moreover, the logical deduction is that the creation of inferior, implicit self-esteem in the female is due to the limitations imposed on her role in Chinese society, as also her impaired communication skills. On the other hand, despite male’s impaired communication skills, his initiative, resolve and social superiority have all given him stronger implicit self-esteem. Greenberg et al. (17) interpret that self-esteem is a product of individual’s adaptation to culture environment, which has a buffering effect on anxiety. Generally, a person with higher self-esteem also shows a better mental health status. Many studies have found that the relation between implicit self-esteem and explicit self-esteem is not close; so, one generally tends to believe that implicit self-esteem and explicit self-esteem are independent, which is in agreement with the mechanism of the double attitude mode. Also, many studies find that implicit self-esteem is most likely to be affected by external factors, and implicit and explicit self-esteem predict discrete behavioral expressions of individuals. For example, researchers find that implicit self-esteem is not related to the level of anxiety reported by the individual, but to the anxiety status reflected by nonverbal behaviour (18). Similarly, the authors find no correlation between the measures of the SDS-R and the IAT, which means that the IAT index is not related to the scores in the SDS-R. This suggests that the relationship between the Deaf/hard of hearing students’ level of implicit self-esteem and depression is not significant. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Понатамошни истражувања |

|

Future research |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

IAT, како мерка на самопочитувањето, има неколку потенцијално проблематични карактеристики. Тоа не е само мерка за самопочитувањето, тоа е заедничка мерка за самопочитувањето и за почитувањето на другите. Личноста што има високо самопочитување и високо почитување кон другите се разликува од личноста што има ниско самопочитување и низок степен на почитување на другите. Понатамошните студии би требало да се спроведат со поголема и поразновидна популација глуви/наглуви за да се споредат нивните развојни карактеристики со оние на личностите што слушаат. |

|

IAT, as a measure of self-esteem, has several potentially problematic properties. It is not simply a measure of self-esteem; it is a joint measure of self-esteem and other-esteem. A person who has high self-esteem and high other-esteem is indistinguishable from a person who has low self-esteem and low other-esteem. Future studies should be conducted with larger and more diverse Deaf/hard of hearing populations in order to compare their developmental characteristics with those of hearing individuals. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Citation: Zheng J. Measuring Self-Esteem of Deaf/Hard of Hearing College Students. J Spec Educ Rehab 2013; 14(1-2):55-65. doi: 10.2478/v10215-011-0033-3 |

||||

|

Article Level Metrics |

||||

|

Литература/References |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

1. Bat-Chava Y. Diversity of deaf identities. Am Ann Deaf 2000; 145(5):420-428. 2. Schlesinger H S A developmental model applied to problems of deafness. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ 2000; 5(4):349-361. 3. Munoz-Bell I M, Ruiz M T. Empowering the deaf. Let the deaf be deaf. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health 2000; 54:40-44. 4. Mulcahy R T. Cognitive self-appraisal of depression and selfconcept: Measurement alternatives for evaluating affective states. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Gallaudet University.12.Swann WB, Schroeder DG. The search for beauty and truth: a framework for understanding reactions to evaluations Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1995; 21(12): 1307-1318. 5. Abrams D, Hogg MA. Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. European Journal of Social Psychology 1988; 18:317-334. 6. Bosson JK, Swann WB, Jr, Pennebaker J W. Stalking the perfect measure of implicit self-esteem: the blind men and the elephant revisited?. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000; 79(4): 631-643. 7. Krause S, Back MD, Egloff B, et al.. Reliability of implicit self-esteem measures revisited. European Journal of Personality 2011; 25:239-251. 8. Greenwald AG, Farnham SD. Using the implicit association test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000; 79(6):1022-1038. 9. Greenwald AG, McGhee, DE, Schwartz J L. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998; 74(6):1464-1480. 10. Karpinski A. Measuring self-esteem using the implicit association test: the role of the other. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2004; 30(1): 22-34.

|

|

11. Swann WB, Schroeder DG. The search for beauty and truth: a framework for understanding reactions to evaluations Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1995; 21(12):1307-1318. 12. Baumeister RF. Esteem threat, self-regulatory breakdown, and emotional distress as factors in self-defeating behavior. Review of General Psychology 1997; 1:145-174. 13. Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF. Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: does self-love or self-hate lead to violence?. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998; 75(1):219-229. 14. Garstecki DC, Erler SF. Older adult performance on the Communication Profile for the Deaf/hard of hearing: gender difference. J Speech Lang Hear Res 1999; 42(4):785-796. 15. Bailly D, Dechoulydelenclave MB, Lauwerier L. Hearing impairment and psychopathological disorders in children and adolescents. Review of the recent literature. Review. Encephale 2003; 29(4 Pt 1):329-337. 16. Crowe TV. Self-esteem scores among deaf college students: an examination of gender and parents' hearing status and signing ability. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ 2003; 8(2): 199-206. 17. Greenberg J, Solomon S, Pyszczynski T, et al. Why do people need self-esteem? Converging evidence that self-esteem serves an anxiety-buffering function. J Pers Soc Psychol 1992; 63(6):913-922. 18. Egloff B, Schmukle SC. Predictive validity of an Implicit Association Test for assessing anxiety. J Pers Soc Psychol 2002; 83(6): 1441-1455. 19. Koole SL, Dijksterhuis A, Van Knippenberg A. What's in a name: Implicit self-esteem and the automatic self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2001; 80:669–685. |

||

Share Us

Journal metrics

-

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 -

IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 -

SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 -

h5-index 7

h5-index 7 -

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

10 Most Read Articles

- PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE / REJECTION AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS WITH AND WITHOUT DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

- RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFE BUILDING SKILLS AND SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT OF STUDENTS WITH HEARING IMPAIRMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR COUNSELING

- EXPERIENCES FROM THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM – NARRATIVES OF PARENTS WITH CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN CROATIA

- INOVATIONS IN THERAPY OF AUTISM

- AUTISM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

- THE DURATION AND PHASES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- REHABILITATION OF PERSONS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY

- DISORDERED ATTENTION AS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL COGNITIVE DISFUNCTION

- DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDERS – AN OVERVIEW

- HYPERACTIVE CHILD`S DISTURBED ATTENTION AS THE MOST COMMON CAUSE FOR LIGHT FORMS OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY