JSER Policies

JSER Online

JSER Data

Frequency: quarterly

ISSN: 1409-6099 (Print)

ISSN: 1857-663X (Online)

Authors Info

- Read: 72483

|

СУБЈЕКТИВНО НАБЉУДУВАНА БЛАГОСОСТОЈБА КАЈ РОДИТЕЛИТЕ НА ДЕЦА СО ПОСЕБНИ ПОТРЕБИ

Реа ФУЛГОСИ - МАСЊАК1,

1Универзитет во Загреб, Едукациско рехабилитациски факултет, Загреб, Хрватска 2проф. психолог, Загреб, Хрватска

3проф. рехабилитатор, Основно училиште „Над липа“ во Загреб

|

|

PERCEIVED SUBJECTIVE WELLBEING OF PARENTS OF CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Rea FULGOSI- MASNJAK1

1University of Zagreb, Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences, Zagreb, Croatia 2Prof. psychologist, Zagreb, Croatia 3Prof. rehabilitator, Primary school „Nad Lipom“, Zagreb |

|

Вовед |

|

Introduction |

|

Од прегледи на литература и претходни истражувања спроведени во Хрватска и светот, може да се забележи дека интересот за квалитетот на живеење и подигнувањето на квалитетот на живеење расте. Исто така се зголемува интересот за испитување на потребите на лицата со инвалидност и нивните семејства. Многу е важно да се разберат потребите на семејствата со членови со инвалидност, поради тоа што тие претставуваат значителен процент од светската популација. Според проценките на Обединетите Нации, инвалидност се појавува кај секој десетти жител на секоја земја, што претставува 450 милиони луѓе, а кога ќе се додадат и членовите на нивните семејства, овој број се зголемува. Законот што се однесува на хрватскиот регистар на луѓе со инвалидност од 2001 година, ја дефинира инвалидноста како трајно ограничување, загуба или намалување на способностите на човекот да достигне одредени физички активности или психички функции соодветни на неговите години, а се однесува на сложени активности и однесување кои се својствени за секојдневниот живот. |

|

From literature review and early studies conducted in Croatia and worldwide, it can be seen that the interest for quality of life and the improvement of the quality of life are increasing. It also appears that the interest for investigating the needs of the persons with disabilities and their families is increasing as well. Understanding the needs of families with a member with disabilities is very important, since they make a significant percent of the world ׳s population. According to the United Nation ׳s estimation, disability appears in every tenth inhabitant of every country, which is about 450 million of people, and this number is increasing when added the members of these families. The Law referring to the Croatian register of people with disabilities from 2001 defines the disability as a permanent restriction, loss or decrease of ability to accomplish some physical activities or psychical function appropriate to age. The term activity refers to complex activities and behaviors which are common for the everyday life. |

|

Како се дефинира квалитетот на живеење? Концептот на квалитетот на живеење е тема од интерес за многу различни научни дисциплини, едукативно-рехабилитациски науки, социјални науки, клиничката медицина и општата популација. Постојат многу теории и дефиниции за квалитетот на живеење и повеќе од 800 прашалници за негово дефинирање. Светската здравствена организација (СЗО) го дефинира квалитетот на живеење како замислена положба во одреден културен, социјален и животен контекст (9). Според членовите на Меѓународната асоцијација за благосостојба (10), квалитетот на живеење е дефиниран како мултидимензионален концепт којшто ги опфаќа: стандардот на живеење, личното здравје, животните достигнувања, личните врски, личната безбедност, поврзаноста во општеството и идната безбедност. Квалитетот на живеење го вклучува процесот на задоволување на потребите и исполнувањето на интересите, личниот избор, вредностите и тенденциите кон различни полиња во различен период од животот. Покрај објективните фактори, како што се социјалните, економските и политичките, исто така постојат и субјективни фактори како што се оценување на физичката, материјалната, социјалната и емотивната благосостојба, личниот раст и животните достигнувања. Врската помеѓу објективните и субјективните делови на квалитетот на живеење не е линеарна, според тоа, измената на објективните фактори не мора да значи промена на субјективните компоненти (11,12). Сите дадени делови на субјективниот квалитет на живеење се под влијание на индивидуален систем од вредности (13). Условите кои придонесуваат за квалитетот на живеење се исто така активни учесници во соработката и комуникацискиот процес, како и при размената во физичката и социјалната средина (14). |

|

How do we define quality of life? The concept of quality of life has been very appealing topic for investigation in different fields of sciences, mostly psychology, educational-rehabilitation sciences, philosophy, social sciences and clinical medicine, mainly concerning the general population. There are many theories and definitions of the quality of life and more than 800 questionnaires for its defining. The World′s Health Organization (WHO) is defining the quality of life as an individual perception of the position in specific cultural, social and environmental context (9). According to the members of the International Well Being Group (10), the quality of life is defined as a multidimensional concept which includes: standard of living, personal health, life achievements, personal relationships, personal safety, community connectedness and future safety. The quality of life includes the process of satisfying the needs and achieving the interests, the personal choices, values and tendencies toward different fields in different periods of the life. Besides the objective factors such as the social, economical and political, there are also subjective factors such as assessment of physical, material, social and emotional wellbeing, personal growth and life achievements. The relation between the objective and subjective components of quality of life is not linear, therefore alterations in the objective factors do not necessary mean alterations in the subjective components (11, 12). All given components of the subjective quality of life are under the influence of individual system of values (13). The conditions which contribute to the quality of life are also active parts of the process of interaction and communication, as well as the exchange in the physical and social environment (14). |

|

Стабилност на субјективниот квалитет на живеење Без разлика на бројните економски и политички промени во светот кои може да нарушат една или неколку димензии на квалитетот на живеење, многу истражувања покажуваат дека нивото на забележаната субјективна благосостојба, во просек е стабилно и позитивно. Бројни истражувања покажаа дека луѓето кои имале негативни и трауматични искуства во минатото, исто така искажуваат задоволувачки и позитивен субјективен квалитет на живеење. Такви примери се луѓето со инвалидност кои не покажуваат трајно опаѓање на нивниот набљудуван квалитет на живеење, затоа што тие на крај се насочуваат кон други вредности и интереси, со цел да надоместат за нивниот инвалидност (15). Такви и слични резултати доведоа до претпоставката дека постои механизам кој би го помогнал одржувањето на набљудуваниот квалитет на живеење на одредено ниво. Robert Cummins во 1995 ја претстави теоријата на хомеостазата на субјективниот квалитет на живеење (10, 12). Механизмот на хомеостазата има улога на контролен систем, во кој лицето ја набљудува сопствената благосостојба во домен кој е специфичен за секој поединец, и го одржува нивото на набљудуваниот квалитет на живеење меѓу позитивните вредности кои се погодни за него (10,16). Schkade и Kahneman (17) исто така ја потврдија оваа теорија. |

|

Stability of subjective quality Regardless the numerous economic and political changes in the World which can disturb one or more dimensions of the quality of life, many studies show that the level of perceived subjective wellbeing is in average positive and stable. Studies have shown that people who had negative or traumatic experiences in their past, also express satisfying and positive subjective quality of life. Such examples are people with disabilities who do not show permanent decrease in their perceived subjective quality of life, because they eventually turn to other values and interests in order to compensate for their disability (15). Such and similar findings lead to the assumption that there is a mechanism for maintaining the perceived subjective quality of life at a certain level. Robert Cummins in 1995 introduced the theory of homeostasis of the subjective quality of life (10, 12). The homeostasis mechanism functions as a control system in which the person observes their own wellbeing within a range specific for each individual and it maintains the level of perceived subjective wellbeing among the positive values which are convenient to that individual (10,16). Schkade i Kahneman (17) also confirmed this theory. |

|

Квалитетот на живеење на семејствата кои имаат член со инвалидност

Детето со развојна пречка има големо влијание врз другите членови на семејството. Достапни истражувања покажаа значајно различни резултати кај ефектите од грижата за членовите со инвалидност врз квалитетот на живеење на целото семејство. Постојат автори кои го застапуваат мислењето дека грижата за член од семејството со инвалидност го подобрува единството и врските помеѓу членовите од тоа семејство, додека од друга страна постојат автори кои тврдат дека инвалидноста го намалува фамилијарниот квалитет на живеење. Видот на детската инвалидност е исто така многу важен фактор. Доколку инвалидноста бара висок степен на зависност од другите членови во семејството, тој може да го намали нивниот квалитет на живеење. Некои истражувања покажаа дека грижењето за член од семејството со инвалидност, ја зголемува семејната кохезија (18) и истото не предизвикува дополнителен стрес врз тоа семејство (19). Процесот на адаптација кон новата ситуација нормално е многу краток и на крајот има позитивни ефекти врз семејството (20, 21). Morrony (19) го потенцира фактот дека институцијалната грижа не е од најдобар интерес за лицата со инвалидност или за нивните семејства. Потешкотиите во грижата за членовите од семејството со инвалидност може да бидат совладани со охрабрување, кое произлегува од задоволството на тој член (23) со позитивен ефект на емотивната врска (24). Авторите Yau и Li Tsang (2) ги дискутираа можните проблеми кои се јавуваат при грижата за член од семејството со инвалидност, и истите ги интерпретираат како период за адаптација и времетраење до целосно прифаќање на ситуацијата. Според нив, проблемот се намалува и изчезнува како што поминува периодот на адаптација по што следува целосно прифаќање на членот од семејството со инвалидност, од страна на самите родители. Родителите сметаат дека нивните животи се збогатени поради нивните деца. За да биде успешна адаптацијата и грижата за членот да има позитивен ефект врз семејството, треба да бидат исполнети неколку услови како што се: хармонични врски во состав на семејството, повисок социо-економски статус и живеење во општини кои пружаат поддршка. |

|

The quality of life of the families with a disabled member

The child with developmental disabilities has a big influence over the other family members. Available studies showed significantly different findings regarding the effects over the quality of life of the whole family when taking care of a disabled family member. There are authors who support the opinion that the care for a disabled family member improves the unity and connections between the family members, while other authors state that it decreases the family’s quality of life. The type of child’s disability is also very important factor. If the disability requires a high level of dependence on the members of the family, it can decrease their quality of life. Some studies report that the care for a family member with disabilities enhances the family cohesion (18) and doesn’t create stressful effect on each family member (19). The process of adaptation in the new situation is usually very short and at the end has a positive effect over the family in general (20, 21). Morrony (19) emphasizes that the institutional care is not in the best interest of the family members with disabilities or their families. The difficulties in the care for the family member with disabilities can be overcome with encouragement elicited by the satisfaction of the disabled (23) and the positive effect of the emotional bonding (24). The authors Yau and Li Tsang (2) discussed the possible issues which can occur while nurturing the disabled family member, and they interpreted them within the frame of adaptation period and total expectance level of the situation. According to them, the issues decrease and disappear as the period of adaptation is passing and the total expectance levels of the member with disabilities and the parents themselves are being established. After, the parents consider as their lives are enriched because of their child. For the adaptation period to be successful and the care for the member to have a positive effect on the family, there are some requirements such as: harmonious relations within the family, higher socio-economical status and living in a supporting community. |

|

Цел на истражувањето |

|

Aims of the study |

|

1. Да се испита постоењето на разлики во набљудуваната субјективна благосостојба помеѓу родителите на децата со моторни пречки, интелектуални пречки и со психомоторни пречки во домените на ПИБ-скалата и Персоналниот индекс на благосостојба; |

|

1. To investigate the existence of differences in the perceived subjective wellbeing between the parents of children with motor disabilities, intellectual disabilities and psychomotor disabilities, in the domain of the PWI scale and the Personal Wellbeing Index. |

|

Методологија на истражувањето |

|

Methodology of work |

|

Учесници Истражувањето беше спроведено врз родители на деца со развојни пречки, N=49, со цел да се одреди нивниот набљудуван квалитет на живеење. Учесниците беа членови на родителски здруженија за родители со деца со развојни недостатоци во Загреб. Учесниците беа волонтери и тестирањето беше анонимно. 80% од испитаниците беа мајки и 20% татковци, од кои што 40,8% имаа вишо образование, 18,4% високо образование и 32,7% имаа средно образование. Поради ограничените ресурси и експлоративната природа на истражувањето, како и легалната и социјална чувствителност на темата, беа избрани три потпримероци на родители кои беа членови на родителски здруженија и кои доброволно се согласија да учествуваат. Поради тоа, примерокот на родители се состоеше од родители кои имаа деца со моторни (28,6%), психомоторни (12,2%) и интелектуални (59,2%) пречки. |

|

Participants The study was carried out over parents of children with developmental disabilities (N=49), in order to determine their perceived quality of life. The participants were members of parental associations for parents of children with developmental disabilities in the town of Zagreb. The participants were volunteers and the testing was anonymous. There were 80% of mothers and 20% of fathers, of whom 40,8% had a college education, 18,4% higher education and 32,7% had a high school education. Considering the limited resources and the explorative nature of the study, as well as the legal and social sensitivity of the topic, three sub samples of parents, all volunteers and members of parental associations were elicited. Respectively, the investigated sample of parents was consisted of parents who had children with motor (28,6%), psychomotor (12,2%) and intellectual (59,2%) disabilities. |

|

Инструмент

Беше користен Меѓународниот индекс на благосостојба - МИБ (16), кој се состои од Персоналниот индекс на благосостојба - ПИБ и Националниот индекс на благосостојба -НИБ. ПИБ-скалата се состои од седум точки на задоволство, секоја од нив припаѓајќи на доменот на квалитетот на живеење: животен стандард, здравје, животни достигнувања, врски, поврзаност со заедницата и идна безбедност. Овие седум домени се теоретски вградени претставувајќи го првото ниво на конструкција на глобалното прашање: Колку сте задоволни од Вашиот живот во целина? |

|

Instrument

The International Wellbeing Index, IWI (16) that was used was consisted of the Personal Wellbeing Index, PWI and the National Wellbeing Index, NWI. The PWI scale contained seven items of satisfaction, each one corresponding to a different standard within the domain of quality of life: standard of living, health, achievements in life, relationships, safety, community-connectedness and future safety. These seven standards were constructed by theory, each representing the basic level in the construction of the generic question: How satisfied are you with your life as a whole? |

|

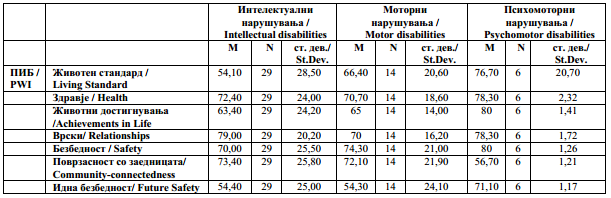

Табела 1. Дескриптивна статистика на резултатите од ПИБ-скалата, според видот на развојниот хендикеп |

|

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the results on the PWI scale according to the type of developmental disability |

|

Според резултатите прикажани во табелата 1, родителите на децата со психомоторни недостатоци се најзадоволни со нивните животни стандарди (M=76,70). Родителите на децата со моторни недостатоци (M=66,40) се помалку задоволни, додека родителите на децата со интелектуални пречки се најмалку задоволни (M=54,10). Најнезадоволни од поврзаноста со општеството се родителите на децата со психомоторни недостатоци (M=56,70), но според животните достигнувања, тие беа задоволни (M=80). Во доменот на здравјето, сите родители покажаа слични резултати. Сите потпримероци на родители изразија задоволство во доменот на врските. Постоеја разлики во доменот на идната безбедност каде родителите на децата со психомоторни пречки (M=71,10) беа повеќе задоволни за разлика од другите. Разликите во резултатите кај ПИБ и НИБ-скалите помеѓу потпримероците на родители не беа статистички значајни, освен во доменот на животниот стандард, каде родителите на деца со психомоторни пречки (M=76,70) покажаа поголемо задоволство отколку другите потпримероци на родители. |

|

According to the results shown in Table 1, the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities were the most satisfied with their life standard (M=76, 70). The parents of children with motor disabilities (M=66, 40) were less satisfied, while lest satisfied were the parents of children with intellectual disabilities (M=54, 10). Most dissatisfied with the community-connectedness were the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities (M=56, 70), but they were the most satisfied regarding life achievements (M=80). In the domain of health, all parents showed similar results. All subsamples of parents expressed satisfaction in the relationship domain. There was a difference in the domain of future safety, in which the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities (M=71, 10) were more satisfied then the rest. The differences in the results on the PWI and the NWI scale between the subsamples of parents were not statistically significant, except in the domain of living standard where the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities (M=76, 70) expressed more satisfaction then the other subsamples. |

|

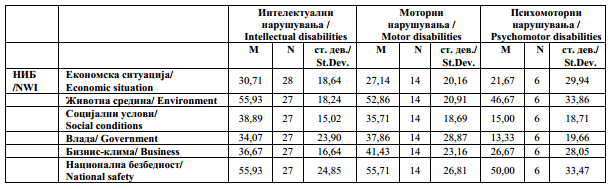

Табела 2. Дескриптивна статистика на резултатите од НИБ-скалата, според видот на развојното нарушување |

|

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the results on the NWI scale according to the type of developmental disability |

|

Резултатите во табелата 2 покажуваат дека сите потпримероци на родители изразиле незадоволство со економскиот статус во Хрватска. Постоеше статистички значајна разлика во доменот на социјалните услови, каде најнезадоволни беа родителите на деца со психомоторни недостатоци (M=15,00). Тие исто така беа најнезадоволни со владата (M=13,33). |

|

The results in Table 2 show that all subsamples expressed dissatisfaction with the economical situation in Croatia. There was a statistically significant difference in the domain of social conditions, were the most dissatisfied were the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities (M=15,00). They were also the most dissatisfied with the government (M=13, 33). |

.jpg)

|

Слика 1.Споредба на вредностите од ПИБ и НИБ-скалите според видот на развојната попреченост |

|

Figure 1.Comparison of the values from the PWI and the NWI scales according to the type of developmental disability |

|

Резултатите прикажани на сликата 1 покажуваат дека родителите на децата со психомоторни недостатоци покажаа поголемо задоволство на ПИБ-скалата, отколку другите потпримероци, но беа најнезадоволни на НИБ-скалата. Најзадоволни на НИБ-скалата беа родителите на децата со интелектуални недостатоци. |

|

The results presented in Figure 1, show that the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities declared greater satisfaction on the PWI scale then the other subsamples, but they were the most dissatisfied on the NWI scale. Most satisfied on the NWI scale were the parents of children with intellectual disabilities. |

|

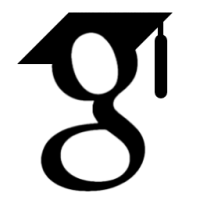

Табела 3. Споредба на дескриптивната статистика на ПИБ-ставките според видот на развојната попреченост |

|

Table 3. Comparison of the descriptive statistics of the PWI items according to the type of developmental disability |

|

Како што е прикажано во табелата 3, добиените резултати не покажаа статистички значајна разлика помеѓу тестираните потпримероци на родители. |

|

As shown in Table 3, the obtained results didn’t show statistically significant differences between the tested subsamples of parents. |

.jpg)

| Слика 2. Споредба на вредностите од ПИБ-скалата според видот на развојното нарушување |

|

Figure 2. Comparison of the values from the PWI scale according to the type of developmental disability |

|

Споредбата на добиените резултати со резултатите на истражувањата спроведени врз родители на деца со аутистични нарушувања и родители на деца без никакви нарушувања (30), покажа дека постојат разлики помеѓу тестираните потпримероци на родители и родителите на деца со аутизам. Резултатите покажаа дека сите родителите на деца со моторни, психомоторни и интелектуални нарушувања ја потврдија нивната субјективно набљудувана благосостојба како подобра отколку онаа на родителите на деца со аутистичен спектар (M= 50,67). Нормативниот опсег во западните земји е 70- 80 % СM, а за светот е 60-80% СM (3). Доколку резултатот падне надвор од границите, квалитетот на животот е загрозен и постои висока шанса за појава на депресивни симптоми (3). Родителите на деца со интелектуални пречки (M=66,70) и моторни нарушувања (M=67,55) се наоѓаа во опсегот на светските рамки, но не и во западните рамки, како што се родителите на деца со психомоторни нарушувања (M=74,52). Родителите на деца со аутистични нарушувања значително отстапија од потпримерокот на родители во ова истражување и не беа во типичниот опсег, ниту според западните ниту според светските стандарди. Врз основа на тоа беше изнесен заклучок дека квалитетот на животот на родителите беше значително нарушен поради потешкотиите и потребите со кои тие се соочуваат поради нивните деца со инвалидност. Ова откритие е важно укажувајќи дека доколку инвалидноста бара висок степен на зависност од членовите на семејството, истата може да го намали квалитетот на животот на тоа семејство. |

|

The comparison of the obtained results with the results of other study carried out on parents of children with autistic disorder and parents of children without disabilities (30) indicated that there were differences between the tested subsamples of parents and parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. The results showed that the parents of children with motor, psychomotor and intellectual disabilities all together stated that their subjective personal wellbeing is better than the one of the parents of children with autism spectrum disorders (M= 50,67). The normative range for the Western countries is 70- 80 %SM and for the World is 60-80%SM (3). If the result falls outside the limits, the quality of life is endangered and there is a higher possibility for depressive symptoms (3). The parents of children with intellectual disabilities (M=66, 70) and motor disabilities (M=67, 55) were in the typical range for the World, but not for the Western countries. Such were the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities (M=74, 52). The parents of children with autistic disorders significantly differed from the subsamples of parents in this study and they were not within the typical range neither for the Western countries nor for the World. Therefore, the conclusion was that their quality of life was significantly disturbed by the difficulty and the demanding conditions of their child’s disability. This finding is of a great importance, because if the disability requires a high level of dependence on the family members, it can decrease the family’s quality of life. |

|

Дискусија |

|

Discussion |

||

|

Според Benjak (30), родителите на деца со аутистично нарушување покажаа значително отстапување од општата популација во смисла на нивниот кавалитет на живеење, а нивните резултати се под просечното ниво на општата популација. Очекувањата беа дека резултатите на ова истражување ќе ги потврдат разликите помеѓу нашите потпримероци на родители. Добиените резултати покажаа дека не постои отстапување помеѓу потпримероците на родители и општата популација во смисла на набљудуваниот квалитет на живеење, но иако без статистичка значајност, постојат разлики помеѓу потпримероците на родители на ПИБ и НИБ-скалите. Поради тоа, може да се заклучи дека набљудуваниот квалитет на живеење се менува според видот и потребите на инвалидност на детето. Со други зборови, како што се зголемува зависноста од помошта на родителот, така опаѓа нивото на набљудуван квалитет на живеење на родителот. Нивниот квалитет на животот е значително зависен од видот и потребата на инвалидност на детето, така што, доколку инвалидноста бара висок степен на зависност од членовите на семејството, тој го намалува квалитетот на животот на тоа семејство. Mohinde и Steiner (26) докажаа дека родителите се под стрес и подложни на депресивно расположение, и исто така живеат со пониско ниво на квалитетен живот. Cummins (3) откри дека семејствата кои се грижат за член со инвалидност, по правило имаат помалку квалитетен животен стил. Семејствата кои имаат член со инвалидност имаат помалку социјални контакти, помалку време за одмор и имаат проблем да бидат прифатени од страна на поширокото семејство (31). Родителите се истоштени од психичките и емотивните напори кои ги вложуваат за да ја изградат врската со своето дете со развојна пречка, од што како резултат произлегува пониското ниво на квалитетен живот. Поради развојните пречки на нивните деца, родителите се поранлив дел од општата популација, кој е изложен на високо ниво на стрес (31). Резултатите покажуваат дека испитуваните потримероци на родители се многу задоволни со своето здравје; родителите на деца со психомоторни недостатоци (M=78,30) се најзадоволни, додека родителите на деца со интелектуални (M=72,40) и моторни недостатоци (M=70,70) се помалку задоволни, додека родителите на деца со аутизам, според Benjak (30), изразија најниско ниво на задоволство (M=58,50). Истражувањата кои охрабуваат позитивен став кон грижата за член со инвалидност кој живее во семејство, потенцираат дека количевството на грижа ја зголемува кохезијата и врската во состав на тоа семејство (19). Авторите Yau и Li Tsang (2) истражуваа можни проблеми кои може да настанат во текот на грижата за член од семејството со инвалидност, и истите ги интерпретираат како период на адаптација и целосно прифаќање на ситуацијата. Според нив, како што периодот на адаптација изминува, проблемите се намалуваат и целосно исчезнуваат, а се појавува целосно прифаќање од страна на членовите на семејството и нивните родители. Родителите сметаат дека нивните животи се збогатени од страна на нивните деца. За адаптацијата да биде успешна и грижата за членот да предизвика позитивни ефекти врз семејството, постојат некои услови како што се: хармонична врска во состав на семејството, добра комуникација во состав на семејството, фамилијарна кохезија, повисок социо-економски статус и живеење во општина која пружа поддршка (2, 3). Во ова истражување, потрпимероците на родители покажаа високо ниво на задоволство со нивните врски; родителите на деца со интелектуални пречки беа најзадоволни (M=79,00), а родителите на деца со психомоторни (M=78,30) и моторни недостатоци (M=70) беа помалку задоволни. Во доменот на социјалната средина, родителите на деца со интелектуални пречки (M=73,40) и моторни недостатоци изразија задоволство, но родителите на децата со психомоторни недостатоци (M=56,70) покажаа пониска сатисфакција. Родителите на деца со аутистично нарушување (30) изразија пониско ниво на сатисфакција (M=49,30) со социјалната средина, споредено со потпримерокот на родители на деца со интелектуални, моторни и психомоторни недостатоци. Родителите од ова истражување беа задоволни со приватните врски и социјалната средина, што претставува предуслов за позитивен ефект кој произлегува од грижата за член во семејството со инвалидност. |

|

According to Benjak (30), the parents of children with autistic disorder have shown significant deviation from the general population in terms of quality of life, their results being below the average for the general population. The expectations from this study were that the results would verify the differences between the subsamples of parents. The obtained results showed that there was no deviation between the subsamples of parents in this study and the general population in terms of perceived quality of life. However, although with no statistical significance, there were differences between the subsamples of parents on the PWI and NWI scale. Therefore, it can be concluded that the perceived quality of life is changing in regards to the type and the demands of the child’s disability. In other words, as the level of required reliance on the parental help is higher, the level of perceived quality of life of the parents is decreasing. Their quality of life is significantly affected by the type and the demands of their child’s disability, so if the disability requires a high level of dependence on the family, it decreases the family’s quality of life. Mohinde and Steiner (26) reported that the parents are stressed and subject to depressive moods and live with lower level of quality of life. Cummins (3) reports that the families that nurture a member with disability, as a rule of thumb have a lower quality of life. The families who care for a disabled person have less social contacts, less time for resting and possibly have an issue with the acceptance from the members of the extended family (31). The parents are exhausted from the physical and emotional efforts they invest in their relationship with their disabled child, which results with lower lifestyle quality. As a result from the developmental disabilities of their child, these parents are more vulnerable segment of the general population exposed to a high level of stress (31). The results show that the investigated subsamples of parents are very satisfied with their health; the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities (M=78, 30) are the most satisfied, while the parents of children with intellectual (M=72, 40) and psychomotor disabilities (M=70, 70) are less satisfied. The parents of children with autistic disorder according to Benjak (30) expressed the lowest satisfaction (M=58, 50) in that area. Studies which encourage the positive attitudes toward care for disabled family member emphasize that the high amount of care increases the cohesion and connectedness within family members (19). The authors Yau and Li Tsang (2) examined the possible issues that can occur along the care for a disabled family member and they understand them as a period of adaptation and total acceptance of the situation. According to them, the issues decrease and completely disappear as the period of adaptation is passing and the total acceptance of the member with disabilities by the parents themselves is taking place. The parents consider that their lives are enriched by their child. In order for the adaptation to be successful and the care for the member to create a positive effect on the family, some demands have to be fulfilled; harmonious relations within the family, good communication among the family members, family cohesion, higher socio-economical status and living in supporting community (2, 3). The subsamples of parents in this study show high satisfaction with their relationships; the parents of children with intellectual disabilities are the most satisfied (M=79,00), the parents of children with psychomotor (M=78,30) and motor disabilities (M=70) were less satisfied. In the domain of social environment, the parents of children with intellectual disabilities (M=73,40) and motor disabilities expressed satisfaction, however, the parents of children with psychomotor disabilities (M=56, 70) showed less satisfaction. The parents of children with autistic disorders (30) showed lower satisfaction (M=49, 30) level with the social environment compared to the sub samples of parents with intellectual, motor and psychomotor disabilities from this study. The parents from this study were satisfied with the personal relationships and the social environment, which is a requirement for creating a positive outcome from the care giving of the disabled member. |

||

|

Заклучок |

|

Conclusion |

||

|

Добиените резултати не покажаа статистички значајна разлика помеѓу потпримероците на родители, а во исто време таквите резултати не отстапија од други национални истражувања врз општата популација (22). Споредбата на добиените резултати со истражувања спроведени врз родители на деца со аутистичен спектар (АСД) (30), покажаа поголема позитивно перцепирана субјективна благосостојба (квалитет на живеење) кај родителите од ова истражување. Добиените резултати покажуваат дека ниската набљудувана субјективна благосостојба (квалитет на живеење) е поврзана со видот и степенот на инвалидност кај детето. Доколку инвалидноста бара поголема зависност од членовите на семејството, тоа го намалува квалитетот на животот на тоа семејство.

|

|

The obtained results didn't show statistically significant difference between the subsamples of parents and at the same time such results did not differ from other investigations, conducted on general population nationwide (22). The comparison of the results from this study showed more positive perception of the subjective wellbeing in parents, when compared to the results from the study carried out on parents of children with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) (30). The obtained results indicate that the lower perceived subjective wellbeing (quality of life) is connected to the type and the level of the child's disability, because if the disability requires a high level of dependence on the family members, it decreases the family’s quality of life. |

||

|

Citation:Fulgosi-Masnjak R, Masnjak M, Lakovnik V. Perceived Subjective Wellbeing of Parents of Children With Special Needs. J Spec Educ Rehab 2012; 13(1-2):61-76. doi: 10.2478/v10215-011-0019-1 |

||||

|

Article Level Metrics |

||||

|

Референци/ References |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Share Us

Journal metrics

-

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 -

IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 -

SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 -

h5-index 7

h5-index 7 -

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

10 Most Read Articles

- PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE / REJECTION AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS WITH AND WITHOUT DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

- RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFE BUILDING SKILLS AND SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT OF STUDENTS WITH HEARING IMPAIRMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR COUNSELING

- EXPERIENCES FROM THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM – NARRATIVES OF PARENTS WITH CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN CROATIA

- INOVATIONS IN THERAPY OF AUTISM

- AUTISM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

- DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDERS – AN OVERVIEW

- THE DURATION AND PHASES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- REHABILITATION OF PERSONS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY

- DISORDERED ATTENTION AS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL COGNITIVE DISFUNCTION

- HYPERACTIVE CHILD`S DISTURBED ATTENTION AS THE MOST COMMON CAUSE FOR LIGHT FORMS OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY