JSER Policies

JSER Online

JSER Data

Frequency: quarterly

ISSN: 1409-6099 (Print)

ISSN: 1857-663X (Online)

Authors Info

- Read: 102198

|

РОДИТЕЛСКИТЕ ИНДИКАТОРИ НА СИГУРНОСНАТА ПРИВРЗАНОСТ НА ДЕТЕТО И УМЕРЕНАТА УЛОГА НА ТЕЛЕСНИТЕ НАРУШУВАЊА КОИ ГИ ИМА ДЕТЕТО: ПРЕФОРМУЛИРАЊЕ НА РОДИТЕЛСКИТЕ ПРОГРАМИ ЗА СЕМЕЈСТВА ВО КОИ ДЕЦАТА СЕ АФЕКТИРАНИ ОД НЕВРОЛОШКА БОЛЕСТ

1Андреа КАПУТО, 2Габриела МАРТИНО, 3Вивијана ЛАНГЕР

1Оддел за Динамичка и Клиничка Психологија – „Сапиенца“ Универзитет во Рим 2Оддел за Когнитивни Науки, Психолошки, Едукативни и Културни студии – Универзитет во Месина |

|

THE PARENTAL PREDICTORS OF CHILD’S ATTACHMENT SECURITY AND THE MODERATION ROLE OF CHILD’S DISABILITY: REFRAMING PARENTING PROGRAMS FOR FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN AFFECTED BY NEUROLOGICAL ILLNESS

1Andrea CAPUTO, 2Gabriella MARTINO, 1Viviana LANGHER

1Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology – “Sapienza” University of Rome 2Department of Cognitive Sciences, Psychological, Educational and Cultural Studies - University of Messina |

|

Примено: 20.11.2017 Прифатено: 05.02.2018 |

|

Recived: 20.11.2017 Accepted: 05.02.2018 Original Article |

|

Вовед

Поголемиот дел од истражувањата покажале дека сигурносната приврзаност има тенденција да ја зголемува автономијата на децата и нивната иницијатива (1) и да развива попозитивна социјална и емоционална способност кај децата, како и да развива подобро когнитивно функциони- рање и физичко и ментално здравје (2, 3). Во таа смисла, иако истражувањето примарно се фокусирало на односот помеѓу мајката и детето, денешните истражувања ја нагласуваат улогата и на двајцата родители, мајките и татковците, како значајна во развојот на врската на приврзаност, која исто така резултира со различен резултат кај децата (4 - 7). Проблемот со сигурносната приврзаност изгледа дека е особено значаен кај децата кои имаат некакво нарушување бидејќи некои делови од минатите истражувања имаат откриено дека нарушувањето кое го има детето може да има влијание врз неговата/нејзината социоемотивна способност и развојот на приврзаноста (8, 9); исто така, постои поголема можност децата кои имаат нарушување да бидат класифицирани како несигурно приврзани (10). Претходно е демонстрирано дека нарушувањето како фактор е помалку веројатно да биде един- ствениот фактор кој придонесува во развојот на несигурна приврзаност, што има поголема врска со психолошката добросостојба на родителите, отколку оној на детето (8). Познато е дека родителската чувствителност е клучен фактор за раз- војот на сигурносна приврзаност кај детето (1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 11) и кога станува збор за дете кое има нарушување, може да биде потешко реализирана можноста на родителот ефективно да комуницира и да ја препознае состојбата на детето, па затоа, тоа може да резултира со поголеми предизвици во постигнувањето на родителската чувствителност кон детето (8, 12-15). Покрај тоа, нарушувањето кај детето може да ги зголеми некои од одговорите на роди- телите што беше утврдено во примерокот на новите мајки, како што е на пример нервозата и лутината кон бебето, одвојување од бебето и одбивност или анксиозност за грижата на бебето (16, 17). Во однос на децата кои имаат невролошки заболувања, нарушувањето е предизвик за родителите, при што влијае на чувствителноста и со тоа се зголемуваат можностите кај детето кое има некоја невролошка состојба да развие несигурна приврзаност кон родителите (8, 10). На пример, децата со вродени деформации имаат тенденција да бидат значително запоставени од нивните мајки кои присвојуваат модели со кои ја отфрлаат интеракцијата со нив, што по- следователно има негативно влијание врз формирањето врски на приврзаност со мајката (18, 19). Во рамките на истражувањето од Mullen (20), кое се однесувало на врските на приврзаност кај децата со церебрална парализа, било заклучено дека ниту присуството ниту сериозноста на ова патолошко нарушување влијаат врз пред- видувањето, туку врз предвидувањето влијае нивото на стрес кое го има негувателот. Marvin и Pianta (21) го проучиле во детали развојот на приврзаноста кај група на деца кои имаат церебрална парализа и епилепсија и откриле дека кај тие деца има поголем ризик во воспоставување не- сигурна приврзаност кога тоа е споредено со децата кои имаат нормален развој, бидејќи родителите негативно реагирале на нарушувањето на нивното дете. Неколку истражувања (22, 23) демонстрирале дека недостигот на решение за дијагнозата на децата од страна на мајките, кај децата со церебрална парализа и епилепсија се по- врзува со несигурна приврзаност кај децата и неавтономна состојба на мозокот кај децата со почит за приврзаноста од страна на мајката. Исто така, некои истражувања имаат сугерирано дека невролошките проблеми (на пример, церебрална парализа и епилепсија) кај децата може да поврзат суштинско несовпаѓање на перцепциите за приврзаноста помеѓу членовите во семеј- ството, во однос на сигурносната приврзаност гледана од перспективата на верувањата на децата и родителите за перспективата која ја имаат децата за приврзаноста кон нив (24). Навистина, емоционалното искуство на родителите и вистинските емотивни услови може да влијаат во начинот на кој тие се однесуваат кон детето (22, 25, 26). Бидејќи сигурносното приврзување на децата е генерално предвидено од страна на способноста на родителите да ја прочитаат, интерпретираат и разберат менталната состојба на децата (27), истражувањата на приврзаноста кај децата со невролошки болести споредена со децата со нормален развој може да придонесе во сфаќањето на интеракцијата на перспективите за приврзаност помеѓу децата и родителите. На та- ков начин, постои можност за поставување постојани програми за интервенција кои би им помогнале на мајките и татковците да развијат сигурна врска на приврзаност со нивните деца кои имаат задоцнувања во нивниот развој.

Цели Првата цел на ова истражување беше да се тестира дали сигурносната приврзаност на детето кон неговите/нејзините мајка и татко може да биде објаснето со неколку варијабли од родителите, во однос на самоперцепцијата на родителите како си- гурни родители и верувањата за сигур- носната приврзаност на детето. Понатаму, ние истражуваме дали постојат ефекти од таквите варијабли на родителите, па дури и го контролираат присуството на нарушувањето во развојот кај детето, особено кога станува збор за невролошките болести. И на крајот, ние ја тестиравме можната умерена улога на пречките во развојот на детето во врската помеѓу перцепцијата на родителите и сигурносната приврзаност на детето. Ова беше направено со цел да се истражи дали присуството на невролошки проблеми кај детето може да го намали или да го промени влијанието на перцепцијата за приврзаност на родителите во однос на сигурносната приврзаност на детето.

Метод

Учесници во истражувањето

Пригоден примерок на српски учесници беше регрутиран, кој беше составен од 50 нуклеарни семејства, вклучувајќи мајки татковци и деца. Подетално, 25 нуклеарни семејства ја образуваа клиничката група којашто се карактеризираше по пречките во развојот на детето; подетално, 19 семејства со деца кои имаа церебрална парализа и 6 семејства со деца кои имаа епилепсија. Учесниците од клиничката група беа регрутирани преку две болници: специјална болница за лица кои имаат церебрална парализа која вклучува две структури (интернатски објект во која се згрижуваат пациентите од нивните први месеци, па сè додека не станат возрасни лица и дневната болница) и болница која е специјализирана за неврологијата кај бебињата и адолесцентите. Критериумите за селекција на нуклеарните семејства кои се дел од клиничката група беа во рамките на семејството да има дете на возраст од 6 до 19 години, со медицинска дијагноза не вклучувајќи ја интелектуалната попреченост. Останатите 25 нуклеарни семејства беа дел од споредбената група, регрутирани од две јавни училишта, средно училиште во Белград и основно училиште од Крагуевац. Критериумот за селекција во компаративната група беше во семејството да има дете на возраст од 6 до 19 години, без медицинска дијагноза, интелектуалната попреченост или други хронични или оневозможувачки болести. Децата кои беа вклучени во компаративната група се совпаѓаа со оние од клиничката, во однос на полот и возрасната група (6-12 години и 13-19 години). За учесниците во истражувањето, родителите обезбедија писмени дозволи, додека децата дадоа усна согласност за спроведување на истражувањето. Процедурите беа спроведени во согласност со етичките стандарди на одговорниот комитет за човечки експерименти.

Мерни единици Сигурносна скала (SS). SS (28) е прашалник создаден за да обезбеди континуитет во мерењето на сигурносната приврзаност кон мајката и таткото. Се состои од 15 прашања (истите и за мајката и за таткото) преку кои се проценува обемот во кој де- тето верува дека личноста за поврзување е спремна и достапна за нив (29). Секое прашање е рангирано на скала од 4 степен, употребувајќи го форматот од Хартер (30) („некои деца.. но...други деца“), каде повисоките резултати покажуваат перцепција на поголема сигурност. Оригиналната скала е развиена за деца на возраст од 6 до 11 години, но исто така била психометриски тестирана кај адолесценти (31). Претходните истражувања покажале добра внатрешна конзистентност на скалата (32), како и нејзината факторска валидност и структурна константност на нејзината нагласувачка структура кај родителите (33). Покрај тоа, некои спојувања беа детектирани кај други мерки на приврзаност, како што се извештаите од самите лица и техниката на прикажување на една приказна за испитување на приврзаноста (31). Исто така биле пријавени социо-емоционалната приспособливост, со- цијалната способност, самодовербата на детето, стратегиите за справување со про- блеми и проблеми со однесувањето (31, 34, 36). Доверливоста во SS во ова истражување е многу добра и за верзијата на мајката (α=0.859) и за верзијата на таткото (α=0.885). Мерки за родителството. Врз основа на моделот за приврзаност кој се применува кај децата и адолесцентите, две други мерки беа испитани и кај мајките и кај татковците преку две скали, составени од 15 прашања, со употребата на Ликартовата скала со 4 степени, кои беа создадени ад хок (ad hoc) за родителите. Првата скала (Каков родител сум јас) има цел да ја процени перцепцијата за приврзаноста на родите- лот со детето како сигурна и компетентна, која се рефлектира на SS. Втората скала (Каков родител сум според моето дете) има цел да ги истражи мислењата за перцепцијата на приврзаност на детето, во однос на тоа што придонесува секој од родителите во однос на приврзаноста од гледна точка на детето кон него/неа. Доверливоста на скалата за перцепцијата на родителите за сигурноста која тие ја влеваат кај детето беше прифатена и од страна на мајката (α=0.669) и од страна на таткото (α=0.786); како и доверливоста на скалата за мислењето на родителите за перцепцијата на детето беше добра и за мајката (α=0.718) и за таткото (α=0.829).

Анализа на податоците Прво, описните статистики од секоја мерка беа испитани и за целокупниот примерок и за клиничкиот/компаративниот потпримерок. Исто така, беше пресметана интеркорелацијата помеѓу овие мерки. Потоа, со цел да се одговори првото прашање од истражувањето, беше направена анализа на повеќекратна регресија со моделот во кој е вклучена перцепцијата на мајката и таткото за сигурноста на родителите и мислењето за перцепцијата на детето, како показатели, и сигурносната приврзаност на детето кон мајката и таткото, како критериум (модел 1). Во однос на второто прашање од истражувањето, попреченоста на детето беше вклучена во моделот 1, како дополнителна коваријанта (модел 2) за да се тестираат потенцијалните промени во пресметните регресиони коефициенти кај мерките на родителите. И на крајот, анализа на регресијата на умереноста беше направена, во согласност со сугестиите дадени од Aiken и West (36). Со цел да се добие целосно стандардизирано решение, сите варијабли беа предвремено стандардизирани (за резултати). Потоа, стандардизираните резултати на попреченоста на детето и секоја од испитаните мерки на родителството беа помножени за да се формира термин за интеракција. Ефектот на умереноста потоа беше тестиран во одделни чекори со употреба на анализата на хиерархиска регресија: во првиот чекор, мерките на родителството и попреченоста на детето беа регресирани врз основа на критериумот (SS мајка и SS татко, редоследно) и во вториот чекор, термините за интеракција беа вклучени во регресионата равенка за да се тестира потенцијалното значајно зголемување на претходно објаснетатаваријанта.

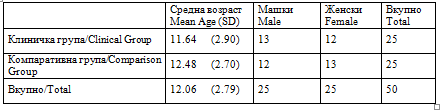

Резултати Во Табела 1 се прикажани карактеристиките на децата коишто учествуваа во истражувањето. Во однос на полот и возраста не е утврдена статистички значајна разлика помеѓу клиничката и компаративната група, по полот χ2(1)=0.080, p=0.777; и по возраст, t(48)=-1.064, p=0.293, и со тоа се потврдува значителното совпаѓање помеѓу двата потпримероци. |

Introduction Most of research showed that secure attachment tends to increase child‟s autonomy and initiative (1) and to develop more positive social and emotional competences, as well as better cognitive functioning and physical and mental health (2, 3). In this regard, albeit research primarily focused on the mother-child dyad, current studies have emphasized the role of both mothers and fathers as relevant to the development of the attachment relationship, which also results in different child outcomes (4-7). The issue of attachment security seems to be particularly important in children affected by disabilities, because some pieces of research have found that the existence of a disability in the child may influence his/her socio-emotional competence and the development of attachment (8, 9); as well, children with disabilities are generally more likely to be classified as insecurely attached (10). However, it is demonstrated that disability alone is unlikely to be the sole factor that contributes to the development of an insecure attachment, which has more to do with the parents‟ psychological well-being, than the child (8). Indeed, it is known that parental sensitivity is a key factor for the development of a secure attachment (1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 11) and that, when dealing with a child with a disability, the parental ability to communicate effectively and recognize a child‟s state may be more difficult, thus resulting in greater challenges in achieving parental sensitivity (8, 12-15). Besides, child‟s disability may increase some parental responses that were found in newly mothers in general samples, such as annoyance and anger towards the infant, detachment and rejection or anxiety about infant care (16, 17). With specific regard to children with a neurological illness, disability appears to challenge parents, undermining sensitivity, and increasing the chances that children with neurological conditions will be insecurely attached (8, 10). For instance, children with congenital malformations tend to be significantly neglected by their mothers, who adopt dismissing interaction modalities, which consequently have a negative impact on the formation of attachment bonds (18, 19). A study by Mullen (20) on attachment relationships among children with a cerebral palsy concluded that the risk of an insecure attachment is predicted by neither the presence nor the gravity of this pathological condition but by the related stress level of the caregiver. Marvin and Pianta (21) examined in detail attachment developments in a group of children affected by cerebral palsy and epilepsy and found that such children were at higher risk of insecure attachment when compared to typically developing children, because of parental negative responses to the child‟s condition. Indeed, several studies (22, 23) demonstrated that the lack of resolution of child‟s diagnosis in mothers of children with cerebral palsy and epilepsy was related to insecure attachment in the child and a non- autonomous state of mind with respect to attachment in the mother. As well, some research has suggested that neurological problems (e.g., cerebral palsy and epilepsy) in the child may be associated with a substantive discrepancy of inter-family attachment perceptions, in terms of attachment security perceived by children and parents‟ beliefs about children's attachment perceptions toward them respectively (24). Indeed, parents' emotional experiences and actual emotional conditions may influence their behavior towards the child (22, 25, 26). Because child‟s attachment security is generally predicted by the parent‟s ability to read, interpret and understand children‟s mental states (27), attachment research on children with a neurological illness compared to typically developing children may contribute to the understanding of the interaction between child‟s and parent‟s attachment perceptions. In such a way, it is possible to set up consistent intervention programs to help mothers and fathers develop secure attachment relationships with their children who have a developmental delay.

Objectives The first goal of the study presented was to test whether child‟s attachment security towards his/her mother and father can be explained by some parental variables, in terms of self-perceptions as secure parents and beliefs about child‟s attachment security. Further, we examined whether the effects of such parental variables still persist and is even controlling for the presence of child‟s disability, specifically neurological illness. Finally, we tested the possible moderation role of the child‟s disability in the relationship between parental perceptions and child‟s attachment security. This was in order to investigate whether the presence of child's neurological problems may reduce or change the influence of parental attachment perceptions on child's attachment security.

Method

Participants

A convenient sample of Serbian participants was recruited, which was overall composed of 50 nuclear families including mothers, fathers and children. In detail, 25 nuclear families constituted the clinical group characterized by child‟s disability; specifically 19 with children affected by cerebral palsy and 6 with epilepsy. The participants of the clinical group were recruited through two hospitals: a specialized hospital for Cerebral Palsy which includes two structures (a residential structure that takes inpatients from their first months of life until adulthood; and a Day Hospital); and the outpatient ward of a hospital specialized in infant and adolescence neurology. For the nuclear families of the clinical group the selection criteria were having a child aged 6-19 years, with a certified medical diagnosis not including intellectual disabilities or comorbidities. The remaining 25 nuclear families constituted the comparison group, recruited from two public schools, i.e. a high secondary school in Belgrade and a low secondary school in Kragujevac. For the comparison group the selection criteria were having a child aged 6-19 years, without a certified medical diagnosis, intellectual disability or other chronic or debilitating diseases. The children included in the comparison group were matched to the clinical ones by gender and age class (6-12 and 13-19 years old). For the participation in the research study, parents provided written informed consent, whereas children provided oral consent. The procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation.

Measures Security Scale (SS). The SS (28) is a self- report questionnaire developed to provide a continuous measure of attachment security towards mother and father. It consists of 15 items (the same for mother and father, respectively) assessing the extent to which the child believes the attachment figure is responsive and available (29). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale using Harter‟s (30) format („Some kids ... but …Other kids‟), with higher scores indicating perceptions of greater security. The original scale was developed for children aged 6-11 years, but was also psychometrically tested with adolescents (31). Previous research reported good internal consistency of the scale (32), as well as its factorial validity and structural invariance of its underlying construct across parents (33). Besides, some associations were detected with other attachment measures, such as self-reports and the attachment story stem technique (31), and social-emotional adjustment, social competence, children‟s global self-esteem, coping strategies and conduct problems have been reported (31, 34, 36). The reliability of the SS in the present study was very good for both the mother (α=0.859) and father version (α=0.885). Parental measures. Based on the attachment model applied to children and adolescents, two other measures were examined for both mothers and fathers through two 15-item scales, by using a 4-point likert scale, that were created ad hoc for the parents. The first scale (What kind of mother/father am I) aims at assessing the attachment perception as secure and competent parent towards the child, which reflects the SS. The second scale (What kind of mother/father does my child think I am) aims at investigating the beliefs about child‟s attachment perception, in terms of attribution that each parent gives to the attachment perceived by the child towards him/her. The reliability of the scale about parental perceptions as secure parent was acceptable for both the mother (α=0.669) and father version (α=0.786); as well, the reliability of the scale about parental beliefs on child's perception was good for both the mother (α=0.718) and father version (α=0.829).

Data analysis Firstly, descriptive statistics of each measure were examined for both the overall sample and clinical/comparison subsamples. Also, intercorrelations among such measures were calculated. Then, in order to answer the first research question, multiple regression analyses were performed, with a model including father‟s and mother‟s perceptions as secure parents and beliefs about child's perception as predictors and child‟s attachment security towards mother and father as criterion, respectively (model 1). With regard to the second research question, child‟s disability was included in the model 1 as additional covariate (model 2) to test potential changes in the estimated regression coefficients of parental measures. Finally, a moderation regression analysis was performed, consistent with the suggested by Aiken and West (36). In order to have a complete standardized solution, all of the variables were standardized in advance (z- scores). Afterwards, the standardized scores of child‟s disability and each of the examined parental measures were multiplied to form the interaction term. The moderation effect was then tested in different steps using hierarchical regression analysis: in the first step parental measures and child‟s disability were regressed on the criterion (SS mother and SS father, respectively) and in the second step the interaction terms were finally included in the regression equation, so to test a potential significant increment in the explained variance.

Results In Table 1 the characteristics of the children participating in the study are shown. No statistically significant differences between the clinical and comparison group are detected by gender, χ2(1)=0.080, p=0.777; and by age, t(48)=-1.064, p=0.293, thus confirming the substantial match between the two subsamples. |

Табела 1. Карактеристики на децата кои учествуваа во истражувањето Table 1. Characteristics of the children participating in the study

|

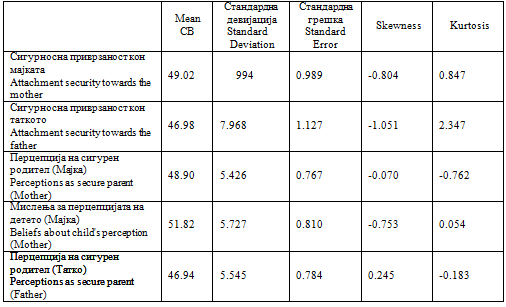

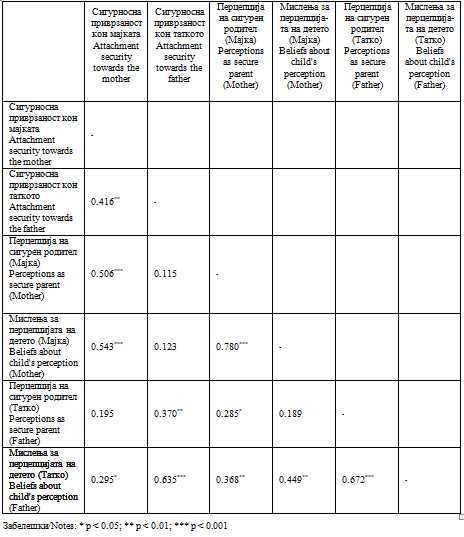

Табелите 2 и 3 ја прикажуваат дескрип- тивната статистика од мерните единици на истражувањето и нивната интерконекција, редоследно. Севкупно, сигурносната при- врзаност на детето кон таткото и мајката се умерено поврзани (r=0.416, p<0.01). Ро- дителските мерки кои се однесуваат на перцепцијата на сигурноста на родителот и мислењето за перцепцијата на детето се високо поврзани и кај мајките (r=0.780, p<0.001) и кај татковците (r=0.672, p<0.001). Покрај тоа, сигурносната приврзаност на детето кон мајката и таткото има тенденција да е умерено поврзана со перспективата на секој родител одделно. Поврзаноста помеѓу мерките на мајките и татковците варира од нула доумерено. |

Tables 2 and 3 show the descriptive statistics of the study measures and their intercorrelations, respectively. Overall, child‟s attachment security toward father and mother are moderately correlated (r=.416, p<.01). Parental measures regarding perceptions as secure parent and beliefs about child‟s perception are highly correlated in both mothers (r=0.780, p<0.001) and fathers (r=0.672, p<0.001). Besides this, child‟s attachment security toward mother and father tends to be moderately correlated with the respective parental perceptions reported by mothers and fathers. Instead, the associations between all mother's and father's measures each other vary from null to moderate. |

Табела 2. Дескриптивна статистика на мерките од истражувањето Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the study measures

Табела 3. Интерконекција помеѓу мерките на истражувањето Table 3. Intercorrelations among the study measures

|

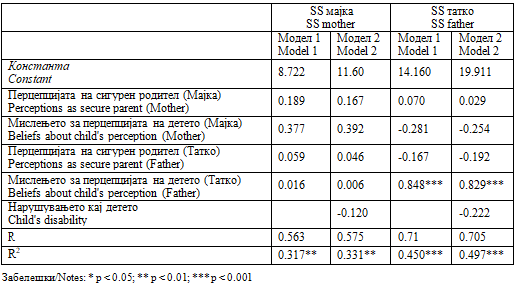

Резултатите од анализата на повеќекрат- ната регресија (Табела 4) укажува на тоа дека испитаните варијабли за родителите успеваат кај 31,7 % кај рејтингот на детето за сигурноста кон мајката и 45 % за реј- тингот на детето за сигурноста кон таткото. Подетално, не се утврдени значајни статистички показатели за рејтингот на детето за сигурноста кон мајката и покрај тоа што проценетиот регресионен коефи- циент за мислењето на мајката за перцеп- цијата на детето е суштински повисок и во моделот 1 (β=0.377, p=0.087) и во моделот 2(β=0.392, p=0.077). Наместо тоа, мисле- њето на таткото за перцепцијата на детето претставува значаен показател за рејтин- гот на детето за сигурноста кон таткото (β=.0848, p<0.001), што сè уште останува статистички значајно, дури и кога е кон- тролирано со нарушувањето кај детето (β=0.829, p<0.001). Потоа, нарушувањето кај детето е поврзано со пониските рејтинзи на детето за сигурноста кон таткото и покрај тоа што коефициентот е под прагот за статистичка значајност (β=-0.222, p=0.050). |

The results of multiple regression analyses (Table 4) indicate that the examined parental variables succeed in accounting for 31.7% of child‟s ratings of security toward mother and for 45% of child‟s ratings of security toward father. In detail, no statistically significant predictors of child‟s ratings of security toward mother are detected, despite the estimated regression coefficient of mother‟s belief about child‟s perception being substantively higher in both model 1 (β=0.377, p=0.087) and model 2 (β=0.392, p=0.077). Instead, father‟s beliefs about child‟s perception represent a meaningful predictor of child‟s ratings of security toward father (β=0.848, p<0.001), which still remains statistically significant even controlling for child‟s disability (β=0.829, p<0.001). Further, child‟s disability is associated with lower child‟s ratings of security toward father, despite its coefficient is not below the threshold for statistical significance (β=-0.222,p=0.050). |

Табела 4. Анализа на повеќекратната регресија за утврдувањето на резултатите од SS кај мајката и од SS кај таткото со помош на мерките за родителите

Table 4. Multiple regression analyses for predicting SS mother and SS father scores by parental measures

|

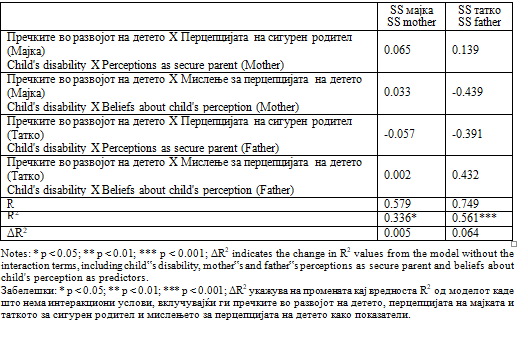

Анализа на регресијата на умереноста (Табела 5) не покажа никаков ефект на ин- теракцијата помеѓу нарушувањето кај де- тето и секоја од испитуваните мерки на родителите, во однос на рејтинзите на де- тето за сигурноста кон мајката и таткото, редоследно. Како и да е, ефектот близок до статистичка значајност се појави во од- нос на интеракциониот термин помеѓу на- рушувањето кај детето и перцепцијата на таткото како сигурен родител (β=-0.391, p=0.055), според која присуството на на- рушувањето кај детето го намалува пози- тивното влијание на перцепцијата на тат- кото како сигурен родител, во однос на сигурносната приврзаност на детето. . |

Regression moderation analyses (Table 5) did not show any effect of the interaction term between child‟s disability and each of the examined parental measures on child‟s ratings of security toward mother and father, respectively. However, a close to statistical significance effect emerged with regard to the interaction term between child‟s disability and father‟s perceptions as secure parent (β=-0.391, p=0.055), according to which the presence of child‟s disability seems to reduce the positive influence of father‟s perceptions as secure parent on child‟s attachment security. |

Табела 5. Анализа на регресионата умереност (интеракциони услови помеѓу нарушувањето кај детето и секоја од испитаните мерки на родителите)

Table 5. Regression moderation analyses (interaction terms between child’s disability and each of the examined parental measures)

|

ДискусијаСо оглед на значајноста на варијаблите за родителите кои придонесуваат во сигурносната приврзаност на детето со пречки во развојот, ова истражување ја испита перцепцијата за приврзаноста во семејства во кои детето има невролошки проблеми и дете со нормален развој. Севкупно, резултатите покажаа дека сигурносната приврзаност на детето кон таткото и мајката е умерено поврзана. Се нагласуваат различ- ните аспекти на врската родител - дете што се значајни за развојот на врската на приврзаност (4-7). Исто така, мерките за родителите кои се однесуваат на сопстве- ната перцепција како сигурен родител и мислењето за перцепцијата на детето се високо поврзани и кај мајките и кај татковците. Затоа се утврдува дека негувањето зависи од психолошкиот и од репрезентативниот процес, каде само перцепцијата на сигурен родител е длабоко поврзана со мислењето за ситуацијата на детето (21). Покрај тоа, поврзаноста помеѓу пер- спективите дете - мајка и дете - татко изгледа дека укажува на практична значајност на таквите психолошки и репрезентативни процеси кај родителите, кои можат да влијаат врз однесувањето на родителите кон детето и во однос на перцепцијата на детето за приврзаноста (22, 25, 26). Потоа, варијациите на асоцијациите помеѓу мерките на мајките и татковците потврду- ваат дека татковците и мајките може да формираат врски на приврзаност кои се независни едни од други, што е конзистентно во постоечката литература (7). Во однос на првото прашање од истражувањето, кое се однесува на родителските варијабли кои влијаат врз сигурноста на приврзаноста на детето, наодите од истражувањето потврдија дека мислењето на таткото за перцепцијата на детето го претставува единствениот статистички значаен показател за рејтингот на детето за сигурноста кон таткото. Ова значи, само мислењето на таткото за перцепцијата на детето создава значајна врска и робустно предвидување за сигурносната приврзаност на детето. Од оваа перспектива, ваквите резултати дозволуваат да се идентификува релевантната улога на родителите која е едвај истражувана во стручната литерату- ра, бидејќи теоријата за приврзаност првично ги поставила татковците како секундарна личност кон која се приврзува детето (7). Во однос на ова, de Minzi (2) открил, кога постои недостиг на достап- ност на таткото до детето, тоа кај него создава чувство на депресија, отколку достапноста на мајките. Одговорот на второто прашање од истра- жувањето, мислењето на таткото за перцепцијата на детето сè уште останува статистички значаен придонесител дури и контролирајќи ја пречката на детето во развојот, која истовремено има тенденција да го намали рејтингот на детето со сигурноста кон таткото (p=0.050). Ова изгледа е линијата која сугерира дека родителската чувствителност како фактор кој генерално оди во прилог на развојот на детето, во однос на контролирањето на емоциите и можноста да остане фокусирано, на кој начин придонесува во обезбедувањето на приврзаноста татко - дете (6, 7, 37, 38). Потоа, во однос на потенцијалната улога на нарушувањето кај детето во врската помеѓу перцепцијата на родителите и сигурносната приврзаност на детето (третото прашање на истражувањето), не се утврдени сигурни ефекти на умереноста, со исклучок во приближност до статистичка значајност (p-=0.055), во однос на ефектот на интеракција помеѓу нарушувањето кај детето и перцепцијата на таткото за сигурен родител. Ова откритие сугерира дека присуството на невролошки проблеми кај детето може да влијае врз позитивното влијание на перцепцијата на таткото како на сигурен родител, во однос на сигурносната приврзаност на детето. Некои интер- претации можеби ќе ги поддржуваат овие резултати, исто така во светлото на суштинското негативно влијание на нарушу- вањето во однос на сигурносната приврзаност на детето кон таткото, која е утврдена во ова истражување. Првата интерпретација може да се потпре на потенцијалната преголема заштита, преголемата вклученост и грижливата тенденција на мајки- те кои имаат невролошки проблеми, бидејќи на нивните деца се гледа како на беспомошни кои се во постојана болка или во здравствена опасност (22). Ова може да доведе до силна двојна врска по- меѓу мајката и детето, исклучувајќи или игнорирајќи ја фигурата татко, што може да придонесе во дискрепанцата на перципираната сигурносна приврзаност помеѓу детето и таткото (24, 39). Од оваа перспектива, детето може да има перцепција на помала сигурносна приврзаност кон таткото и како последица на тоа, таткото може прогресивно да се чувствува како несигурен родител. Друго објаснување на овој резултат може да се однесува на ниското ниво на вклучување на татковците на децата кои имаат пречки во развојот во споредба со оние кои имаат деца со нормален развој (40). Во рамките на врската помеѓу таткото и детето, вклучувањето и високата стимулација за играње претставуваат клучни фактори во развојот на сигурносна приврзаност на детето (6, 37, 38). Како и да е, татковците на децата со пречки во развојот може да кажат дека е тешко да започнат високо стимулативно однесување и вклученост како сигурен родител, што придонесува во ретката сигурносна приврзаност на детето кон таткото. Одредени ограничувања на ова истражување мора да бидат признати. Прво, генерализацијата на овие наоди не може да биде земена предвид поради погодната природа на примерокот на истражувањето. Покрај тоа, транскултурната валидност е ограничена бидејќи примерокот е соста- вен само од српски испитаници. Исто така, малиот број учесници во примерокот не е конзистентно за добивање статистички значајни резултати во поголемиот број случаи, затоа нашите наоди треба да се сметаат како прелиминарни и идните истражувања треба да се спроведат врз поголем примерок со кој ќе можат да се потврдат и подобро да се објаснат резул- татите, исто така и преку кроскултурна валидност на истражувањата. Друго ограничување се однесува на недостигот за тоа да се земат предвид видот и сериозноста на невролошките проблеми и надворешните фактори (на пример, финансиските проблеми, недостигот на социјална поддршка и дополнителните барања од негувателите) кои можат поразлично да придонесат кај стресот на родителите поврзан со тоа што имаат дете кое има пречки во развојот. Во оваа смисла, испитувањето на таквите фактори во идните истражувања може подлабоко да го раздвои севкупниот импакт на врските на сигурносна приврзаност. Без оглед на тоа, додадената вредност на ова истражување е надминувањето на ограничувањата на претходните истражувања, особено фокусирањето на врската мајка – дете, преку истражувањето на врските на приврзаност во врска со тријадата мајка – татко – дете. Во светло на овие резултати, интеракцијата помеѓу таткото и детето изгледа како ветувачки предмет за истражување за да се разбере влијанието на нарушувањето кај детето врз сигурносната приврзаност. Од психолошко-клиничка перспектива (42), родителската чувствителност, во однос на можноста на таткото да ја сфати умствената состојба на детето, изгледа е клучен фактор за целокупната промоција на психолошката благосостојба и приврзаноста и кај децата кои имаат нарушување и кај децата кои немаат нарушување. Исто така, ова истражување може да придонесе за преформулирање на родителските програми кои се адресирани од семејствата на децата со невролошки проблеми (43). Покрај тоа, посигурната приврзаност во рамките на семејството може да придонесе во идните приврзаности во училишниот контекст, па затоа треба да се поддржуваат поефективните инклузивни процеси (9, 44, 45). Особено, родителските програми (46) треба да ја земат предвид перцепцијата на таткото за тоа дали е сигурен родител, на пример обезбедувањето на високо стимулативни игри поврзано со чувствителноста на родителот. Ова оди во насока да се превенира не ангажираноста во рамките на врската помеѓу таткото и детето, бидејќи перцепцијата на таткото како сигурен родител може да претставува заштитнички фактор кој ќе ја подобри сигурносната приврзаност на детето со пречки во развојот.

Авторите изјавуваат дека немаат добиено средства од ниту еден извор за ова истражување. Авторите изјавуваат дека нема конфликт на интереси. |

DicussionGiven the relevance of parental variables contributing to the attachment security of children with a disability, the present research study explored attachment perceptions in families with children with neurological problems and with typical development. Overall, the results showed that child‟s attachment security toward father and mother are only moderately correlated, thus emphasizing different aspects of the parent-child relationship that is important in the development of the attachment relationship (4-7). As well, parental measures regarding self-perceptions as secure parent and beliefs aboutchild's perception are highly correlated in both mothers and fathers respectively, thus confirming that caregiving depends on psychological and representational processes, where self-perceptions as secure parents are deeply connected with beliefs and attributions about child's state (21). Besides this, the association between child- mother and child-father respective perceptions seems to indicate the practical relevance of such parental psychological and representational processes, which may influence parents' behavior towards the child and in turn the child‟s attachment perceptions (22, 25, 26). Then, the varying associations between mother‟s and father's measures seem to confirm that fathers and mothers may form attachment relationships independent of each other, consistent with the literature(7). With regard to our first research question about parental variables affecting child's attachment security, the study findings confirmed that father‟s beliefs about child's perception represent the sole statistically significant predictor of child's ratings of security toward father. This means that, albeit the correlations between child's and parents‟ attachment perceptions mentioned above, only father's beliefs about child's perception makes a meaningful and robust prediction of child's attachment security. From this perspective, such a result allows the identification of the relevant paternal role that is scarcely examined in literature, because attachment theory originally placed fathers as secondary attachment figures (7). In this regard, de Minzi (2) found that father‟s lack of availability is more predictive of feelings of depression in children than motheravailability. To answer our second research question, father‟s beliefs about child‟s perception still remain a statistically significant contributor even controlling for child‟s disability, which at the same time tends to lower child‟srating of security toward father (p=0.050). This seems to be in line with what suggested about paternal sensitivity as a factor that may generally favor child‟s development of emotional regulation and ability to stay focused, thus contributing to secure father- child attachment (6, 7, 37,38). Then, with regard to the potential role of the child‟s disability in the relationship between parental perceptions and child‟s attachment security (third research question), no solid moderation effects were detected, with the exception of a close to statistical significance (p=0.055) interaction effect between child‟s disability and father‟s perceptions as secure parent. This finding seems to suggest that the presence of child‟s neurological problems might inhibit the positive influence of father‟s perceptions as secure parent on child‟s attachment security. Some interpretations may be advocated for this result, also in the light of the substantive negative impact of disability on child‟s attachment security toward father found in our study. A first interpretation may rely on the potential overprotective, overinvolved, and solicitous tendency of mothers of children with neurological problems, because their children are perceived as helpless, in constant pain, or in medical danger (22). This could lead to a strong mother-child dual relationship, excluding or ignoring the figure of father, which may contribute to a discrepancy in perceived attachment security between child and father (24, 39). From this perspective, the child may perceive less attachment security toward his/her father and as a consequence the father may progressively feel more and more insecure as parent. Another explanation of this result may refer to the lower levels of involvement in fathers of children with a disability compared with those with typically developing children (40). Within the father-child relationship, involvement and highly stimulating play represent key-factors for developing attachment security (6, 37, 38). However, fathers of children with a disability may find it more difficulty to engage in such activities – given that physical play may be more difficult for children with disabilities to participate in (41) – and thus feel insecurity when they are unable to engage in highly stimulating play (40). In this sense, child‟s disability may prevent father‟s engagement in highly stimulating behavior and involvement as secure parent, which in turn contributes to a scarce child‟s attachment security. Some limitations need to be acknowledged about the present study. At first, the generalization of our findings can be called into question due to the convenient nature of the study sample; besides, trans-cultural validity is almost limited because our sample was entirely composed by Serbian respondents. Also, the low sample size does not consent to get statistically significant results in most of cases, therefore our findings should be considered preliminary and future research carried out on more extensive samples may confirm and better explain our results, also through cross- cultural validation studies. Another limitation refers to the lack of consideration for type and gravity of neurological problems and for external factors (e.g., financial burdens, lack of social support and the added demands as a caregiver) that may differently contribute to the parental stress associated with having a child with a disability. In this sense, the examination of such factors in future studies may further disentangle the overall impact on secure attachment relationships. This notwithstanding, the added-value of our study is the overcoming of the limitations of previous research, mainly focused on the mother-child dyad, through the exploration of attachment relationships within the mother-father-child triad. In the light of our results, the father-child interaction seems to be a very promising research field for the understanding of child‟s disability-related impact on secure attachment. From a psychological clinical perspective (42), paternal sensitivity – in terms of father‟s ability to understand the child‟s state of mind – seems to be a keyfactor for the overall promotion of psychological well- being and attachment in both children with and without a disability. As well, this study may contribute to reframe supportive programs addressed to families with children affected by neurological problems (43). Besides, more secure attachment relationships within the family may sustain future attachments also in the school context, thus supporting more effective inclusive processes (9, 44, 45). In particular, parenting programs (46) should take into account the father‟s perceptions as secure parent, for example sustaining highly stimulating play along with sensitivity. This is in order to prevent disengagement within the father-child relationship, because father‟s perceptions as secure parent may represent a protective factor improving attachment security of children with disabilities.

The authors declare that there is no source of funding. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. |

|

Референци / References |

|

1. von der Lippe A, Eilertsen D, Hartmann E,Killèn K. The role of maternal attachment in children's attachment and cognitive executive functioning: A preliminary study. Attachment & Human Development 2010; 12:429-444. doi:10.1080/14616734.2010.501967.

2. de Minzi M. Gender and cultural patterns of mothers‟ and fathers‟ attachment and links with children‟s self-competence, depression and loneliness in middle and late childhood. Early Child Development & Care 2010; 180:193-209. doi:10.1080/03004430903415056

3. Ranson KE, Urichuk LJ. The effect of parent-child attachment relationships on child biopsychosocial outcomes: A review. Early Child Development & Care 2008; 178(2): 129-153. doi:10.1080/03004430600685282

4. George MRW, Cummings E, Davies PT. Positive aspects of fathering and mothering, and children‟s attachment in kindergarten. Early Child Development & Care 2010; 180:107-119. doi:10.1080/03004430903414752

5. Goodsell TL, Meldrum JT. Nurturing fathers: A qualitative examination of child-father attachment. Early Child Development & Care 2010; 180: 249- 262. doi:10.1080/03004430903415098

6. Grossmann K, Grossmann KE, Fremmer-Bombik E, Kindler H, Scheuerer-Englisch H, Zimmermann P. The uniqueness of the child-father attachment relationship: Fathers' sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16-year longitudinal study. Social Development 2002; 11: 307-331. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00202

7. Hazen N, McFarlandL, Jacobvitz D, Boyd-Soisson E. Fathers' frightening behaviours and sensitivity with infants: Relations with fathers' attachment representations, father-infant attachment, and children's later outcomes. Early Child Development & Care 2010; 180(1-2): 51-69. doi:10.1080/03004430903414703

8. Howe D. Disabled children, parent-child interaction and attachment. Child & Family Social Work 2006; 11(2): 95-106. doi:10.1111/j.1365- 2206.2006.00397

9. Rea M, Ferri R, Nemola A, Langher V, Lai, C. Attachment relationship to teacher and intensity of emotional expression in children with Down syndrome in regular kindergarten and nursery school. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 2016; 41: 1 -31. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2015.1106453

10. Clements M, Barnett D. Parenting and attachment among toddlers with congenital anomalies: Examining the strange situation and attachment Q- sort. Infant Mental Health Journal 2002; 23(6): 625–642. doi:10.1002/imhj.10040.

11. Posada G, Kaloustian G, Richmond M, Moreno A. Maternal secure base support and preschoolers‟ secure base behavior in natural environments. Attachment & Human Development 2007; 9: 393- 411.

12. Abbeduto L, Seltzer M, Shattuck P, Krauss M, Orsmond G, Murphy MM. Psychological well- being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, Down syndrome, or Fragile X Syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation 2004; 109: 237-254. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017

13. Baker BL, Blacher J, Crnic KA, Edelbrook C. Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children with and without developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation 2002; 107:433-444.

14. Higgins DJ, Bailey SR, Pearce JC. Factors associated with functioning style and coping strategies of families with a child with an autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Research & Practice 2005; 9:125-137.

15. Perry A. A model of stress in families of children with developmental disabilities: Clinical and research applications. Journal on Developmental Disabilities 2005; 11:1-16.

16. Busonera A, Cataudella S, Lampis J, Tommasi M, Zavattini GC. Psychometric properties of the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire and correlates of mother-infant bonding impairment inItalian new mothers. Midwifery 2017; 55: 15-22. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.08.011

17. Cataudella S, Lampis J, Busonera A, Marino L, Zavattini GC. From parental-foetal attachment to parent-infant relationship: a systematic review about prenatal protective and risk factors. Life Span and Disability 2016; XIX 2: 185-219.

18. Capuzzi, C. (1989). Maternal attachment to handicapped infants and the relationship to social support. Research in Nursing & Health, 12, 161– 167. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770120306.

19. Hadadian A. Attitudes toward deafness and security of attachment relationships among young deaf children and their parents. Early Education and Development 1985; 6: 181– 191. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed0602_6.

20. Mullen SW. The impact of child disability on marriage, parenting, and attachment: Relationships in families with a child with cerebral palsy. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 1997; 58(7-B): 3969.

21. Marvin RS, Pianta RC. Mothers‟ reaction to their child‟s diagnosis: Relations with security of attachment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 1996; 25: 436–445.

22. Barnett D, Hunt KH, Butler CM, McCaskill IV JK, Kaplan-Estrin M, Pipp-Siegel S. Indices of attachment disorganization among toddlers with neurological and non-neurological problems. In Solomon J, George C, eds. In: Attachment disorganization. New York, US: Guilford Press, 1999: 189–212.

23. Walsh AP. Representations of Attachment and Caregiving: The Disruptive Effects of Loss and Trauma. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2003; 64(3-B): 1511.

24. Langher V, Scurci G, Tolve G, Caputo A. Perception of attachment security in families with children affected by neurological illness. PSIHOLOGIJA 2013; 46(2): 99-110. doi: 10.2298/PSI1302099L

25. Ketelaar M, Volman MJM, Gorter JW, Vermeer A. Stress in parents of children with cerebral palsy: What sources of stress are we talking about?. Child: Care, Health and Development 2008; 34(6): 825–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365–2214.2008.00876.x.

26. Wirrell EC, Wood L, Hamiwka LD, Sherman EMS. Parenting stress in mothers of children with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior 2008; 13(1): 169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.02.011.

27. Meins E. Sensitivity, security and internal working models: Bridging the transmission gap. Attachment & Human Development 1999; 1: 325- 342.

28. Kerns KA, Klepac L, Cole AK. Peer relationships and preadolescents‟ perceptions of security in the mother-child relationships. Developmental Psychology 1996; 32: 457–466. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.3.457

29. Kerns KA, Aspelmeier JE, Gentzler AL, Grabill CM. Parent–child attachment and monitoring in middle childhood. Journal of Family Psychology 2001; 15: 69–81. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.69

30. Harter S. Perceived competence scale for children. Child Development 1982; 53: 87–97. doi:10.2307/1129640

31. Van Ryzin MJ, Leve LD. Validity evidence for the security scale as a measure of perceived attachment security in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 2012; 35:425–431. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.014

32. Dwyer KM. The meaning and measurement of attachment in middle and late childhood. Human Development 2005; 48:155–182. doi:10.1159/000085519

33. Marci T, Lionetti F, Moscardino U, Pastore M, Calvo V, Altoé G. Measuring attachment security via the Security Scale: Latent structure, invariance across mothers and fathers and convergent validity. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 2017. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2017.1317632

34. Barone L, Lionetti F, Dellagiulia A, Galli F, Molteni S, Balottin U. Behavioural problems in children with headache and maternal stress: Is children‟s attachment security a protective factor? Infant and Child Development 2015; Advance online publication.doi:10.1002/icd.1950

35. Booth-Laforce C, Oh W, Kim AH, Rubin KH, Rose-Krasnor L, Burgess K. Attachment, self- worth, and peer-group functioning in middle childhood. Attachment & Human Development 2006; 8: 309–325.doi:10.1002/icd.1950

36. Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage,1991.

37. Brown G, McBride B, Shin N, Bost K. Parenting predictors of father-child attachment security: Interactive effects of father involvement and fathering quality. Fathering 2007; 5:197-219. doi:10.3149/fth.0503.197

38. Freeman H, Newland L, Coyl D. New directions in father attachment. Early Child Development & Care 2010; 180(1-2):1-8. doi:10.1080/03004430903414646

39. Langher V, Kourkoutas E, Scurci G, Tolve G. Perception of the security of attachment in neurologically ill children. Social & Behavioral Science 2010; 5: 2290-2294. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.451

40. Lopez S. Mothers' and Fathers' Attachment Relationships with Children who Have Disabilities. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations 2013; 2068. Available from:https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2068

41. Martino G, Caprì T, Castriciano C, Fabio,RA. Automatic Deficits can lead to executive deficits in ADHD. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 2017; 5(3). doi: 10.6092/2282- 1619/2017.5.1669

42. Langher V, Caputo A, Martino G. What happened to the clinical approach to case study in psychological research? A clinical psychological analysis of scientific articles in highimpact-factor journals. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 2017; 5(3): 1-16. doi:10.6092/2282- 1619/2017.5.1670

43. Kourkoutas E, Langher V, Vitalaki E, Ricci ME. Working with Parents to Support Their Disabled Children‟s Social and School Inclusion: An Exploratory Counseling Study. Journal of Infant, Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy 2015; 14(2): 143-145. doi:10.1080/15289168.2015.1014990

44. Caputo A, Langher V. Validation of the Collaboration and Support for Inclusive Teaching (CSIT) scale in special education teachers. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 2015; 33(3): 210–222.

45. Langher V, Ricci ME, Propersi F, Glumbic N, Caputo A. Inclusion in Mozambique: a case study on a cooperative learning intervention. Cultura Y Educaciòn: Culture and Education 2016; 28(1): 42- 71. doi:10.1080/11356405.2015.1120447

46. Cataudella S, Lampis J, Busonera A, Zavattini GC. Parenting after preterm birth: Link between infant medical risk and premature parenthood. A Pilot Study. Minerva Pediatrica 2016; 68(5):319-329.

Share Us

Journal metrics

-

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 -

IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 -

SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 -

h5-index 7

h5-index 7 -

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

10 Most Read Articles

- PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE / REJECTION AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS WITH AND WITHOUT DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

- RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFE BUILDING SKILLS AND SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT OF STUDENTS WITH HEARING IMPAIRMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR COUNSELING

- EXPERIENCES FROM THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM – NARRATIVES OF PARENTS WITH CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN CROATIA

- INOVATIONS IN THERAPY OF AUTISM

- AUTISM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

- DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDERS – AN OVERVIEW

- THE DURATION AND PHASES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- REHABILITATION OF PERSONS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY

- DISORDERED ATTENTION AS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL COGNITIVE DISFUNCTION

- HYPERACTIVE CHILD`S DISTURBED ATTENTION AS THE MOST COMMON CAUSE FOR LIGHT FORMS OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY