JSER Policies

JSER Online

JSER Data

Frequency: quarterly

ISSN: 1409-6099 (Print)

ISSN: 1857-663X (Online)

Authors Info

- Read: 30519

|

ОСЕТЛИВОСТ НА ПОТКРЕПУВАЊЕ КАЈ

РЕЦИДИВИСТИ И НАСИЛНИ ПРЕСТАПНИЦИ

Зоран КИТКАЊ1

Катерина НАУМОВА2

|

REINFORCEMENT SENSITIVITY

IN REOFFENDERS AND VIOLENT OFFENDERS

Zoran KITKANJ1

Katerina NAUMOVA2

|

|

ВОВЕД

|

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between personality and crime has

been vastly investigated in theoretical and empirical

studies in different scientific domains. Over the years

various scientific theories have emerged in an effort to

elaborate the importance of individual differences in

personality as predisposing factors of antisocial

behaviour and criminal offending, but also as potential

predictors of the effectiveness of offender

resocialization and prison treatment programs.

Among the numerous psychological perspectives on

antisocial and criminal behaviour (1), the

Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST) has recently

sparked increasing research interest. RST represents a

neuropsychological model of personality, developed by

psychologist Jeffrey Gray (2,3), and based upon

individual differences in reactions to punishing and

rewarding stimuli. The theory was substantially revised

in 2000 by Gray and McNaughton (4). The revised

model proposes three principal motivation/emotion

systems: the Fight-Flight-Freeze System (FFFS), the

Behavioural Inhibition System (BIS) and the

Behavioural Approach System (BAS). RST thus

constitutes a theory of central emotion/motivational

states that mediate reactions to motivationally

significant (i.e., ‘reinforcing’) stimuli (5).

The Fight-Flight-Freeze System (FFFS) is responsible

for mediating fear reactions to aversive (threatening,

punishing or frustrating) stimuli, leading to avoidance

and escape behaviours or attempted elimination (anger

and attack). FFFS activity reduces the discrepancy

between the immediate threat and the desired state (i.e.,

safety). An associated personality factor with this

system comprises fear-proneness and avoidance.

The Behavioural Inhibition System (BIS) is responsible

for resolving different types of goal conflicts when

facing desired but also potentially threatening stimuli.

This system generates the emotion of anxiety, that is

primarily involved in inhibition of conflicting

behaviours and risk assessment. The BIS increases the

negative valence of stimuli, until a behavioural

resolution occurs manifested as approach or avoidance.

The associated personality factor comprises worry proneness and anxious rumination, resulting in a

constant state of looking-out for possible signs of

danger. Underactive BIS leads to risk proneness (e.g.,

psychopathy) while overactive BIS leads to risk

aversion (generalized anxiety). Both conditions

encompass sub-optimal conflict resolution. The BIS

serves several functions: it interrupts ongoing

behaviour (it inhibits ongoing appetitively and

aversively-motivated behaviours); it initiates ‘passive

avoidance’, i.e. cautious approach and risk assessment

aimed at gathering information on the threat posed by

the environment or, in some situations, withholding

from entry into a threatening environment. Other

processes associated with the BIS, are worry and

rumination about possible danger; obsessive thoughts

about the possibility of something unpleasant

happening; and behavioural disengagement, when the

threat is unavoidable.

The Behavioural Approach System (BAS) mediates

reactions to appetitive stimuli. This system generates

the emotion of ‘anticipatory pleasure’. The associated

personality factor comprises optimism, reward

orientation and impulsiveness. An overactive BAS

delineates a disposition toward addictive, high-risk and

impulsive patterns of behaviour. Corr (5) proposes a

multidimensional conceptualization of distinct but

related BAS processes: Reward Interest represents the

initial motivation to seek out potentially rewarding places, activities and people; Goal Drive-Persistence

relates to actively pursuing desired goals, particularly

when immediate reward is not available; Reward-

Reactivity denotes the excitement and pleasure of

doing things well; and Impulsivity entails behaviours

closer to the final goal (reinforcer), when planning and

restraint of behaviour are no longer present.

According to RST, differences in human temperament

and reactivity can be explained by individual

differences in the functioning of the three systems and

their interaction (6). BAS and BIS are reciprocally

connected, each operating to inhibit behaviour

governed by the other. A balance between the systems

can be achieved only at low levels of activity in both.

Corr and McNaughton (7) point out that joint

activation of these systems increases arousal as a result

of conflicting motivations, resulting in subtractive

decision-making. However, one overactive system with

a deficient other poses a high risk for social adjustment

as well.

Empirical studies show that an overactive BIS leads to

social withdrawal and emotional distress and an

overactive BAS leads to risky, antisocial behaviour (8).

Dysinhibition, as a prominent feature of criminal

behaviour (9) can also result from an overactive BIS,

an underactive BIS, or a BAS that is more active than

the BIS (10). Research also shows that two BAS

dimensions, impulsivity and reward interest, are often

confirmed risk factors of antisocial and criminal

behaviour (11,12,13).

Studies also demonstrate that antisocial individuals are

less sensitive to punishment (underactive BIS) and

highly sensitive to rewards (overactive BAS). The

rewarding effect stems from the execution of the

offense (14). For example, Morgan, Bowen, Moore and

van Goozen (15) found higher BAS and lower BIS

sensitivity in male adolescent offenders as compared to

non-offenders. Bacon, Corr and Satchell (16) have

further found that antisocial behaviour is associated

with goal-drive persistence in males and impulsivity in

females. Investigating the associations between the

motivational systems and psychopathic tendencies,

Broerman, Ross and Corr (17) report that primary

psychopathy is negatively related to the BIS and the

FFFS, while positively related to BAS goal-drive persistence. Secondary psychopathy is positively

related to BAS impulsivity. The FFFS was found to be

incrementally predictive of primary but not secondary

psychopathy. Leue, Brocke, & Hoyer (18) compared

male sex offenders and non-offenders and found that

higher reward sensitivity, impulsivity and anxiety

discriminated the offenders from the non-offenders.

Previously mentioned studies on RST and crime have

mostly been focused on characteristics that distinguish

offenders from non-offenders. Less frequent is the

more refined comparison of offenders who have

committed different types of crimes. But as Canter and

Youngs (19) point out assigning offenders to a

particular type of criminality has to take into

consideration the context of the crime and the stage in

the offender’s criminal and psychological

development.

Considering the lack of empirical research in offending

subgroups our study aims to examine whether RST

facets can differentiate reoffenders from primary

offenders and violent from nonviolent offenders.

Method

Participants and procedure

The participants are male offenders (N=162)

incarcerated in three penitentiary institutions in

Macedonia: Penitentiary facilities Idrizovo and Stip,

and Kumanovo Prison. These are institutions with

largest accommodation capacities. The first two are

closed institutions, while the third one is semi-open.

The average age of the participants is 36 years (±10.5,

age range: 18-65), while the average age when they

committed the currently sanctioned offense is 31 years

(±9.9). Most of the offenders are Ethnic Macedonians

(77%), have secondary education (52%), were

employed prior to incarceration (74%) and are not

married (46%). As part of their resocialization process

most of the offenders (59%) have certain working

engagements inside the penitentiary facility. On

average, the duration of the prison sentence in the

sample is just over seven years (87 months, range: 6-

300 months, 3 offenders were serving a lifetime

sentence). Regarding offending type, 64 participants

are reoffenders (penal recidivists) and 69 are violent offenders. We used the official prison records to split

the offenders in groups. No significant differences

were detected regarding sociodemographic

characteristics in offender subgroups (age, education,

marital and previous work status). With respect to

criminological characteristics, the only significant

difference was detected between violent and nonviolent

offenders, regarding sentence length, which is

an expected finding due to the nature of the criminal

acts (Мv = 8.6 ± 4.9 years > Мnv = 6.3 ± 3.8 years , t

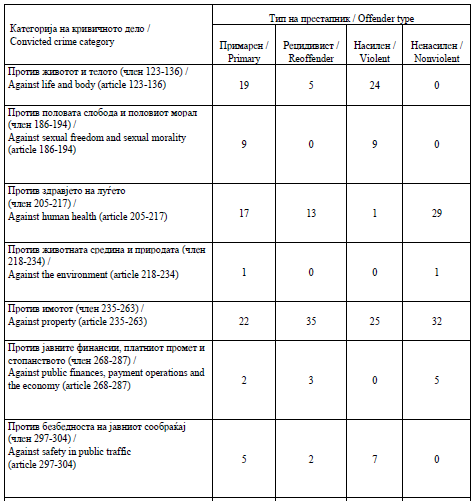

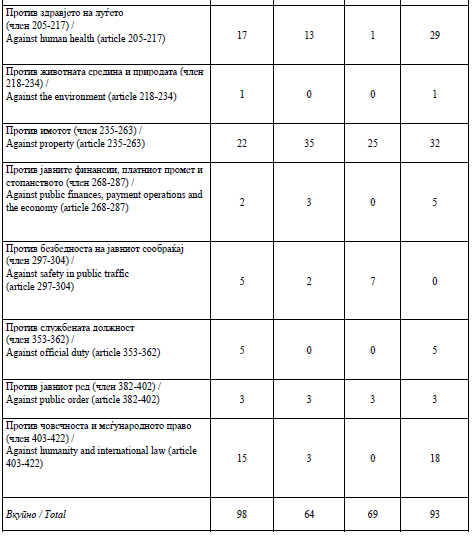

(117) = 3.27, p < 0.01). A detailed description of the

sample is provided in Table 1. with respect to

convicted crime categorization. The criminal acts were

categorized according to the Criminal Code of

R.Macedonia.

|

Табела 1. Структура на примерокот според категоријата на извршени кривични дела

Table 1. Sample structure according to convicted crime categorization

|

Податоците се прибирани во периодот август-сеп-

тември 2017 година преку интервјуа спроведени од

страна на членовите на тимовите за ресоцијализација (мал дел во нивно присуство од страна на еден од авторите на истражувањето). Не беа евидентирани индикатори на неискреност на испитаниците кои би предизвикале систематска грешка во мерењето. Само неколку испитаници беа исклучени од анализата поради некомплетни или невалидни одговори. Од сите испитаници е добиена информирана согласност за учество во истражувањето.

Мерни инструменти

Прашалник за процена на личноста според теори-

јата на осетливост на поткрепување (Reinforcement

Sensitivity Theory of Personality Questionnaire,

RST-PQ) (20). Станува збор за неодамна конструиран инструмент во согласност со ревидираниот модел на теоријата на осетливост на поткрепување, што се обидува да ги надмине различните слабости на претходно конструираните мерки поврзани со оваа теорија. Прашалникот се состои од 65 тврдења со кои се проценуваат четири домени на осетливоста на поткрепување. Одговарањето се врши со помош на четиристепена Ликертова скала на одговори, каде 1=воопшто не ме опишува, 2=малку ме опишува, 3=умерено ме опишува и 4=сосема ме опишува.

Првиот домен што се проценува со инструментот е

системот борба-бегство-блокирање што опфаќа

однесувања од типот бегство, блокирање и активно

избегнување. Оваа супскала се состои од 10 тврдења, а коефициентот на внатрешната конзистентност утврден во ова истражување е α = 0.81.

Вториот домен е системот на бихевиорална инхиби-

ција, во рамки на кој се прави дистинкција помеѓу

одбранбено приближување кон опасни стимули кои

може и кои не може да се избегнат. Како одговори на

опасни стимули што може да се избегнат вклучени се прекин на тековното однесување, бихевиорална процена на ризик и претпазливост и загриженост. Од

друга страна, како одговори на неизбежни опасни

стимули вклучени се опсесивни мисли и бихевиорал-

на неангажираност. Супскалата се состои од 23 твр-

дења, а Кронбах алфа-коефициентот во овој

примерок изнесува α = 0.91.

Третиот домен е системот на бихевиорална акти-

вација, што е операционализиран преку четири

компоненти: заинтересираност за награди, истрај-

ност во постигнувањето на цели, реактивност на награди и импулсивност. Преку заинтересираноста

за награди, се проценува отвореноста кон нови

искуства и можности кои потенцијално може да

предизвикаат задоволство (7 тврдења, α = 0.76). Ис-

трајноста во постигнувањето на цели ја проценува

мотивираноста да се дефинираат цели и нивни

компоненти кои водат до постигнување на одредена

награда, односно задоволство, што често пати може

да вклучува жртвување на краткотрајни или непо-

средни награди/задоволства, а истовремено опфаќа и одржување на долгорочна позитивна мотивираност

кога не е достапна непосредна награда (7 тврдења, α= 0.73). Реактивноста на награди го опфаќа генери-

рањето и доживувањето на награда (задоволство)

кога нештата се одвиваат во посакувана насока, што

овозможува позитивно поткрепување на однесува-

њето (10 тврдења, α = 0.78). Импулсивноста се

состои од отсуство на планирање и брзи реакции (8

тврдења, α = 0.71).

Авторите на овој прашалник, како дополнување на

трите системи, вметнале и дополнителна супскала,

како четврти домен на осетливоста на поткрепување,

а тоа е дефанзивната борба со која се проценуваат

бихевиорални реакции кога единката е соочена со

многу интензивна и непосредна закана и кога не се

возможни други можности за бегство (8 тврдења, α =

0.81).

Резултати

Во Табела 2 се прикажани дескриптивните статистики за сите супскали на користениот прашалник. Утврдена е умерена тенденција на групирање на податоците кон пониските оценки на супскалата борба бегство-блокирање, додека поистакната тенденција кон групирање на податоците кон повисоките оценки е утврдена на супскалите истрајност на целта и

реактивност на награди, како димензии на системот

на бихевиорална активација.

|

The data was collected during August and October in

2017 in a series of one-on-one interview sessions with

the members of the resocialization staff (a small

proportion in their presence by one of the study

authors). No indicators of participants’ dishonesty were

detected that could systematically affect the results.

Only few offenders were excluded from the analyses

due to missing or invalid responses. All participants

provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Measures

Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of Personality

Questionnaire (RST-PQ) (20). This is a recently

developed instrument in alignment with the revised

RST model, specifically designed to address various

drawbacks of previous RST measures. It consists of

65 items measuring three thematic facets. A four-point

Likert-style scale is offered with the following

response options: not at all, slightly, moderately, and

highly, as a a response key to the question “How

accurately does each statement describe you?”

The first measured facet is the Fight-Flight-Freeze

System (FFFS) encompassing flight, freeze and active

avoidance behaviour. The subscale consists of 10

items and the internal consistency coefficient obtained

in this study is α = 0.81.

The second facet is the Behavioural Inhibition System

(BIS), that incorporates a distinction between

defensive approach to avoidable and unavoidable

dangerous stimuli. Motor interruption, behavioural

caution/risk assessment, and worry are assigned as

responses to avoidable dangerous stimuli, while

obsessional thoughts, and behavioural disengagement

are assigned as responses to unavoidable dangerous

stimuli. This subscale consists of 23 items and the

obtained Cronbach’s alpha in this study is α = 0.91.

The third facet is the Behavioural Approach System

(BAS), operationalized through four subcomponents:

Reward Interest, Goal-Drive Persistence, Reward

Reactivity, and Impulsivity. Reward Interest (RI)

measures openness to new experiences and

opportunities that are potentially rewarding (7 items, α

= 0.76). Goal-Drive Persistence (GDP) measures the

motivation to put in place goals and sub-goals to achieve an ultimate aim of obtaining a reward,

although often at the expense of a short-term or

immediate reward, as well as the maintenance of

positive motivation over time when an immediate

reward is not available (7 items, α = 0.73). Reward

Reactivity (RR) relates to the generation and

experience of reward (i.e., ‘pleasure’) when things are

going well and provides the positive reinforcement for

BAS behaviour (10 items, α = 0.78). Impulsivity (I)

consists of non-planning and fast reactions (8 items, α

= 0.71).

The authors of RST-PQ propose that an additional

factor should be included as a separate scale and a

fourth facet, i.e. Defensive Fight, that taps into

behavioural reactions when confronted with a high

intensity and immediate threat and when other forms

of escape are not available (8 items, α = 0.81)

Results

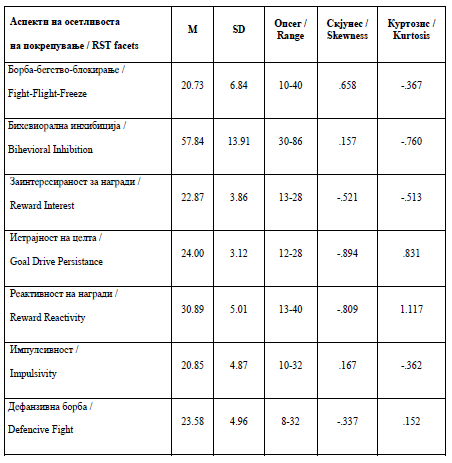

Table 2. presents descriptive statistics on all RST-PQ

scales. A moderate tendency of data grouping towards

lower scores is registered in the Fight-Flight-Freeze

System (FFFS) scale, while a more pronounced

tendency of data grouping towards higher scores is

registered in the Goal-Drive Persistence (GDP) and

Reward Reactivity (RR) scales as part of the

Behavioural Approach System (BAS).

|

Табела 2. Дескриптивни статистици за аспектите на осетливоста на поткрепување (N=162)

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for RST facets (N=162)

|

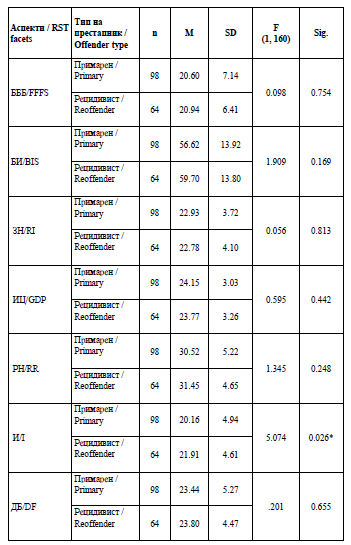

In order to assess the discriminant value of RST facets

in differentiating reoffenders from primary offenders

and violent from nonviolent offenders we used

univariate analysis of variance.

In the first analysis we compared reoffenders with

primary offenders (Table 3) and detected only one

significant difference between the groups in the

domain of the Behavioural Approach System (BAS).

Impulsivity (I) (i.e. non-planning and fast reactions)

was significantly more pronounced in reoffenders F

(1, 160) = 5.07, p < 0.05, g = 0.36.

|

Табела 3. Разлики во аспектите на осетливоста на поткрепување меѓу рецидивистите и примарните

престапници

Table 3. RST facets differences between reoffenders and primary offenders

Забелешка: БББ=систем борба-бегство-блокирање, БИ=систем на бихевиорална инхибиција,

ЗН=заинтересираност за награди, ИЦ=истрајност на целта, РН=реактивност на награди,

И=импулсивност, ДБ=дефанзивна борба

Note. FFFS = Fight-Flight-Freeze System; BIS=Bihevioral Inhibition System; RI=Reward Interest; GDP=Goal-Drive Persistence;

RR=Reward Reactivity; DF=Defensive Fight

* p < 0.05

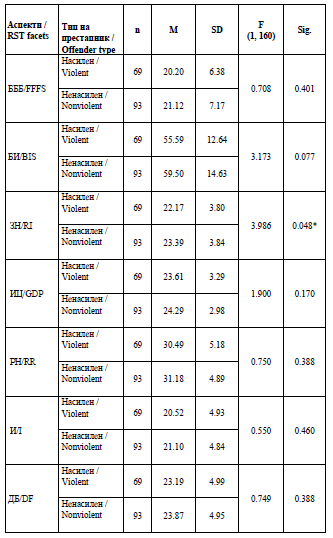

Табела 4. Разлики во аспектите на осетливоста на поткрепување меѓу насилните и ненасилните

престапници

Table 4. RST facets differences between violent and nonviolent offenders

Забелешка: БББ=систем борба-бегство-блокирање, БИ=систем на бихевиорална инхибиција,

ЗН=заинтересираност за награди, ИЦ=истрајност на целта, РН=реактивност на награди,

И=импулсивност, ДБ=дефанзивна борба

Note. FFFS = Fight-Flight-Freeze System; BIS=Bihevioral Inhibition System; RI=Reward Interest; GDP=Goal-Drive Persistence;

RR=Reward Reactivity; DF=Defensive Fight

* p < 0.05

|

Во втората анализа беа споредувани насилните со

ненасилните престапници (Табела 4). И во овој случај се покажа дека насилните престапници се разликуваат од ненасилните само во однос на една димензија на системот на бихевиорална активација. Во овој случај, кај насилните престапници е утврдена значајно пониска заинтересираност за награди F (1, 160) = 3.99, p <0.05, g = 0.32 што ги одредува како помалку отворени за нови искуства и можности кои потенцијално може да предизвикаат задоволство.

Дискусија

Проучувањето на особините на личноста, концепту-

ализирани согласно со ревидираниот модел на тео-

ријата на осетливост на поткрепување, кај различни

групи престапници покажа дека само две димензии на системот на бихевиорална активација независно ги диференцираат повторните од примарните сторители,

односно насилните од ненасилните сторители.

Посилно истакнатата импулсивност кај рециди-

вистите е поврзана со слаба регулативна моќ на кон-

тролните механизми - когнитивни, емоционални

и/или бихевиорални, што ги предиспонира овие прес-

тапници кон рецидивизам. Иако овој аспект на

системот на бихевиорална активација се активира во

финалните фази од достигнувањето и консумирањето

на „наградата“, во ситуации кога е прекумерно акти-

вен, всушност може да го попречи реализирањето на

долгорочните цели. Крупиќ (Krupic) и Кор (Corr) (21)

ја нарекуваат оваа димензија „посакување“, дефи-

нирајќи ја како амбициозно тежнеење кон повеќе

ресурси и посакување на повеќе ресурси, при што

наведуваат емпириски наоди дека оваа црта е

поврзана со т.н. „брз стил на живот“, согласно со

теоријата на животната историја. „Брзите“ единки

според овој модел се повеќе ориентирани кон

експлоатирање на другите, повеќе се антисоцијално

насочени, храбри, активни, агресивни, помалку

дружељубиви, склони кон преземање ризици и

доминантни. Во контекст на ресоцијализацијата на

престапници со вакви особини, импулсивноста прет-

ставува ризик. Поради тоа, програмите за третман

треба да ги земат предвид специфичните стадиуми од криминалниот и психичкиот развој на престапникот, каде импулсивното однесување се појавува како деструктивен процес.

Кај насилните престапници, пак, беше утврдена по-

ниска заинтересираност за награди отколку кај

ненасилните престапници, што упатува на тоа дека кај нив постои послаба желба и тенденција за барање нови задоволства. Крупиќ (Krupic) и Кор (Corr) (21) го дефинираат овој аспект на системот на бихевиорална активација како ʼпоттикнувачка мотивацијаʻ.

Кога овој вид мотивација е послабо изразен, тоа

резултира со инхибирање на пристапот кон потен-

цијални задоволства (т.е. послаба проактивност).

Понатаму, тоа укажува и на послаба тенденција кон

когнитивно истражување и пониско изразена екстра-

верзија како мотивациска снага. Иако е маргинална

статистичката значајност на разликата меѓу престап-

ниците, сметаме дека е важна, не само во контекст на криминалитетот, туку и во контекст на ресоцијали-

зацијата. Заинтересираноста за награда е првиот че-

кор кон постигнување на зададена цел. Доколку ја

разгледуваме од аспект на примарни индивидуални

предиспозиции, извршувањето на насилен престап

повеќе е последица на контекстуални околности

отколку на силна желба за постигнување одредена

цел, при што, не смее да се занемари разновидната

природа на насилните престапи карактеристични за

оваа група испитаници. Кантер (Canter) и Јангc

(Youngs) (19) соодветно посочуваат на важноста на

наративното значење на криминалното дело за самиот престапник. Во отсуство на такви податоци можеме само да шпекулираме за потенцијалната улога на примарната мотивација. Од друга страна, неопходно е да се испита и можноста намалената заинтересираност за награди кај нив да претставува последица на корективната функција на процесот на ресоцијализација. Активноста на мотивациските системи влијае на можностите за стекнување нови животни искуства, меѓутоа и новите животни искуства влијаат на осетливоста на поткрепување. Оттука, уште повеќе се нагласува потребата од посветување дополнително внимание на индивидуалните разлики во посакувањето и пристапувањето кон потенцијални награди како субјективно перципирани компоненти на програмите за третман. Трета можност е да ги разгледаме овие наоди од аспект на особините на извршените кривични дела од страна на ненасилните престапници, кај кои е значајно поизразена заинтересираноста за награди. Во двете доминантни категории на дела поради кои им е изречена тековната затворска казна (против здравјето на луѓето и против имотот), всушност станува збор за производство/трговија со дроги/психотропни супстанци, односно кражби - два типа престапи кои имаат нагласен лукративeн ефект, односно јасно одредена апетитивна дразба. Иако наодите од ова истражување потврдуваат дека осетливоста на награди има подискриминативна

функција кај престапниците (11-14), отколку осетли-

воста на казни, исклучително е важно да се нагласи

дека податоците откриваат многу повеќе сличности

отколку разлики во особините на личност кај

споредуваните групи престапници. Тоа посочува на

неопходноста од дополнително проучување на

ефектите од искуствата поврзани со животот во

затворот, како фактори кои потенцијално посилно го

определуваат функционирањето на престапниците од примарните индивидуални предиспозиции. Со оглед на тоа што примерокот е хетероген во однос на видот на извршените кривични дела, но прилично хомоген согласно со постапката на избор на испитаниците вклучени се главно соработливи престапници, социјално адаптирани и работно ангажирани, чие однесување во текот на издржувањето на казната во најголем дел е проценето како позитивно - сметаме

дека следните истражувања во оваа област може да се фокусираат на споредба на престапници во однос на специфични кривични дела, а не на широки категории престапи, како и испитување на интеракцијата меѓу рецидивизмот и одделните категории престапи, земајќи ги предвид и криминогените потреби на затворениците. Ваквиот вид истражувања може да обезбедат насоки за подиференцирани и индивидуализирани форми на третман.

|

In the second analysis we compared violent with

nonviolent offenders (Table 4). Again, we detected

only one significant difference and it also encompasses

a feature of the Behavioural Approach System (BAS).

Reward Interest (RI) is significantly lower in violent

offenders F (1, 160) = 3.99, p < 0.05, g = 0.32 defining

them as less open to new experiences and opportunities

that are potentially rewarding in comparison to nonviolent

offenders.

Discussion

The investigation of personality traits as

conceptualized within the revised RST framework in

different types of offenders showed that the linear

combination of RST facets does not discriminate

reoffenders and violent offenders. Only two

dimensions of the BAS can independently differentiate

recidivism and violent offending.

Higher impulsivity in reoffenders relates to

dysregulated control mechanisms, either cognitive,

emotional and/or behavioural that predisposes them to

recidivism. Although this BAS aspect represents the

final stages of reward capturing and consummation,

when overactive it can actually inhibit the attainment

of long-term goals. Krupic & Corr (21) label this

dimension ‘wanting’, defining it as ambitious striving

and desiring more resources and offer empirical

evidence that this trait is associated with the so called

‘fast lifestyle’ according to the Life History Theory.

‘Fast’ individuals according to this model are more

exploitative/antisocial, bold, active, aggressive, less

sociable, impulsive, prone to risk-taking, and

dominant. In the context of resocialization impulsivity

poses a risk. Treatment programs should address the

specific stages both in the criminal and in the

psychological development process of the offender

where impulsive behaviour tends to occur as a

disruptive force.

The detected lower reward interest in violent offenders

suggest that they generally show a weaker desire and

tendency toward seeking new rewards. Krupic & Corr

(21) define this aspect of the BAS as ‘incentive

motivation’. Lower incentive motivation thus inhibits

the approach toward potential rewards (i.e. less might potentially determine offending behaviour more

significantly that primary personality dispositions.

Considering the heterogeneity of the sample with

respect to convicted crimes, as opposed to the

homogeneity with respect to participant recruitment -

mainly cooperative offenders were recruited, who are

socially adapted, have working engagements in the

facilities and whose behaviour was mainly assessed as

positive - we recommend that future studies should

focus on comparisons of perpetrators of specific

crimes, and not wide categories of offenses, as well as

on examining the interaction of recidivism and separate

offence types, accounting also for the criminogenic

needs of the offenders. These research approaches can

provide guidelines for differentiated and tailor made

types of treatment.

|

Литература / References:

1. Moore M. Psychological Theories of Crime and

Delinquency. Journal Of Human Behavior In The

Social Environment 2011; 21(3): 226-239.

2. Gray JA. The Neuropsychology of Anxiety: An

Enquiry into the Functions of the Septo-Hippocampal

System. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

3. Gray JA.The neurophysiology of temperament. Strelau

J, Angleitner A, eds. In: Explorations in temperament:

International perspectives on theory and measurement.

New York, NY: Plenum, 1991:105-128.

4. Gray JA, McNaughton N. The Neuropsychology of

Anxiety: An Enquiry into the Functions of the Septo-

Hippocampal System. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 2000.

5. Corr P. Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST):

Introduction. Corr P, ed. In: The reinforcement

sensitivity theory of personality. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press, 2008: 1-44.

6. Corr P, McNaughton N. Reinforcement Sensitivity

Theory and Personality. Corr P, ed. In: The

reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008:

155-187.

7. Elovainio M, Kivimäki M. Models of personality and

health. Corr P, Matthews G, eds. In: The Cambridge

handbook of personality psychology. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press, 2009: 205-227.

8. Knyazev GD, Wilson GD, Slobodskaya HR.

Behavioural activation and inhibition in social

adjustment. Corr P, ed. In: The reinforcement

sensitivity theory of personality. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press, 2008: 415-430.

9. Wallace JF, Newman JP. RST and psychopathy:

associations between psychopathy and the behavioral

activation and inhibition systems. Corr P, ed. In: The

reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008:

398-414.

10. Gomez, R. Personality and attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder. Corr P, Matthews G, eds. In:

The Cambridge handbook of personality psychology.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009:

704-716.

11. Hansen EB, Breivik G. Sensation seeking as a

predictor of positive and negative risk behaviour

among adolescents. Personality and Individual

Differences, 2001; 30: 627–640.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00061-1.

12. Maneiro L, Gómez-Fraguela JA, Cutrín O, Romero E.

Impulsivity traits as correlates of antisocial behaviour

in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences,

2016; 104: 417–422.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.045.

13. Satchell L, Bacon A, Firth J, Corr P. Risk as reward:

Reinforcement sensitivity theory and psychopathic

personality perspectives on everyday risk-taking.

Personality and Individual Differences, 2018; 128:

162-169.

14. Fonseca A, Yule W. Personality and antisocial

behavior in children and adolescents: An enquiry into

Eysenck's and Gray's theories. Journal Of Abnormal

Child Psychology, 1995; 23(6): 767-781.

doi:10.1007/bf01447476

15. Morgan JE, Bowen KL, Moore SC, van Goozen SHM.

The relationship between reward and punishment

sensitivity and antisocial behavior in male adolescents.

Personality and Individual Differences, 2014; 63:122–

127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.054.

16. Bacon A, Corr P, Satchell L. A reinforcement

sensitivity theory explanation of antisocial behaviour.

Personality And Individual Differences, 2018; 123: 87-

93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.008

17. Broerman R, Ross S, Corr P. Throwing more light on

the dark side of psychopathy: An extension of previous

findings for the revised Reinforcement Sensitivity

Theory. Personality And Individual Differences, 2014;

68: 165-169. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.024

18. Leue A, Brocke B, Hoyer J. Reinforcement sensitivity

of sex offenders and non-offenders: An experimental

and psychometric study of reinforcement sensitivity

theory. British Journal of Psychology, 2008; 99: 361–

378.

19. Canter D, Youngs D. Personality and crime. Corr P,

Matthews G, eds. In: The Cambridge handbook of

personality psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press, 2009: 780-798.

20. Corr PJ, Cooper AJ. The Reinforcement Sensitivity

Theory of Personality Questionnaire (RST-PQ):

Development and Validation. Psychological

Assessment, 2016; 28(11): 1427-144.

21. Krupić D, Corr P. Moving Forward with the BAS:

Towards a Neurobiology of Multidimensional Model

of Approach Motivation. Psihologijske Teme, 2017;

26(1): 25-45.

Share Us

Journal metrics

-

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 -

IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 -

SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 -

h5-index 7

h5-index 7 -

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

10 Most Read Articles

- PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE / REJECTION AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS WITH AND WITHOUT DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

- RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFE BUILDING SKILLS AND SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT OF STUDENTS WITH HEARING IMPAIRMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR COUNSELING

- EXPERIENCES FROM THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM – NARRATIVES OF PARENTS WITH CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN CROATIA

- INOVATIONS IN THERAPY OF AUTISM

- AUTISM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

- DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDERS – AN OVERVIEW

- THE DURATION AND PHASES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- REHABILITATION OF PERSONS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY

- DISORDERED ATTENTION AS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL COGNITIVE DISFUNCTION

- HYPERACTIVE CHILD`S DISTURBED ATTENTION AS THE MOST COMMON CAUSE FOR LIGHT FORMS OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY