JSER Policies

JSER Online

JSER Data

Frequency: quarterly

ISSN: 1409-6099 (Print)

ISSN: 1857-663X (Online)

Authors Info

- Read: 64453

|

ДОСТИГНУВАЊE И ИНКЛУЗИЈА НА УЧЕНИЦИТЕ СО И БЕЗ ПОСЕБНИ ОБРАЗОВНИ ПОТРЕБИ (ПОП)

Маркус ГЕБХАРД,

Универзитет во Грац |

|

ACHIEVEMENT AND INTEGRATION OF STUDENTS WITH AND WITHOUT SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL NEEDS (SEN) IN THE FIFTH GRADE

Markus GEBHARDT,

University of Graz |

|

Примено: 05.02.2012 |

|

Recived:05.02.2012 |

|

Училиштен успех на учениците со ПОП во интегративни и изолирани услови |

|

School performance of students with SEN in integrative and segregated settings |

|

|

|

|

|

Развојот на децата со посебни потреби во инклузивните наспроти посебните училишта, |

|

The development of special needs children in integrative versus special schools is currently a |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Социјалната активност на учениците во интегративни и изолирани услови |

|

Social participation of students in integrative and segregated settings |

|

|

|

|

|

Покрај училишниот успех, социјалната активност е клучна област за училишниот развој на децата со посебни потреби (11, 16). Големо компаративно истражување спроведено во Швајцарија од страна на Haeberlin и сор. (11) докажа дека инклузивните ученици се почувствувале помалку популарни и се изјасниле како помалку прифатени за разлика од неинклузивните ученици (11). Понатаму, Klicpera и Gasteiger Klicpera (16) испитале десет интеграциски форми со 175 ученици, од кои 37 биле интегрирани деца со посебни потреби. Слично, резултатите од ова испитување покажуваат негативна слика за социјалната интеграција на учениците со посебни потреби. Споредено со учениците без ПОП, тие имаат помалку пријатели, се чувствуваат помалку прифатени, погрешно се третирани и покажуваат чувство на осаменост. Исто така, слични резултати се најдени во Германија (17) и Норвешка (18). Децата со ниски социјални способности и проблеми во однесувањето особено се сметани за високо ризична група со потенцијал да постанат чудни од инклузивен и специјален аспект (19). |

|

Beside the school performance, social participation is a key area for the educational development of special needs children (11, 16). Major comparative study carried out in Switzerland by Haeberlin et al. (11) pointed out that integrated students felt more unpopular and rated themselves as less accepted than the non-integrated students (11). Moreover, Klicpera and Gasteiger Klicpera (16) examined ten integrative forms among 175 students, of which 37 were integrated special needs children. Similarly, the findings of this survey offered a rather negative view on the social integration of special needs students. Compared to the students without SEN, they had fewer friends, felt less accepted, were victimized and indicated feelings of loneliness. In addition, similar results were found in Germany (17) and Norway (18). Children with low social competence plus behavioural problems could particularly be considered as high-risk group of becoming oddity in both integrative and special forms (19). |

|

|

|

|

|

1. Истражувачко прашање |

|

1. Research questions |

|

|

|

|

|

Во Штаерска, 77.3% од учениците со посебни потреби се образовани во инклузивни училници (22). Во Австрија не се достапни резултатите поврзани со успехот и социјалната интеграција во сличниот едукативен систем (23). Во моментот, истражувањето во врска со едукативниот успех и социјалното учество на учениците со посебни потреби во германскиот регион се заснова на пробни истражувања или училници каде инклузивното школство е воведено од неодамна.

|

|

77.3% of the students with special needs in Styria are schooled in integrated classrooms (22). In Austria, no studies that display the results on school performance and social integration in a similar educational system are available (23). At the moment, the research of the educational performance and social participation of students with special needs from the German regions is based on a trial studies or classrooms where integrated schooling has been recently introduced.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Метод |

|

Method |

|

|

|

|

|

На крајот на академската година, осум инклузивни одделенија и еден посебен клас од петто одделение беа набљудувани во Грац во однос на нивните академски достигнувања и социјалната интеграција. За истражувањето беа користени стандардизирани прашалници и тестови. Овие тестирања беа спроведени кај сите ученици од инклузивните одделенија, вклучувајќи ги учениците со и без ПОП. Тестирањето беше спроведено во првите два часа од два последователни школски денови. Во зависност од одделението, тестот одзеде од 70 до 100 минути дневно. Кога беше потребно, помошници ги помагаа учениците со ПОП според принципот еден на еден за читање и пишување. После тестирањето на групата, беше спроведен десетминутен тест за читање (со декодирање на зборови). |

|

At the end of the academic year, eight integrative classes and one special class from 5th grade were surveyed in Graz, in terms of their academic performance and social integration. The survey used standardized questionnaires and tests. These tests were conducted with all students in integrative forms, including students with and without SEN. The testing was conducted in the first two hours of two consecutive school days. Depending on the class, the test took between 70 and 100 minutes per day. When it was deemed as necessary, assistants supported the SEN students with reading and writing on a one-to-one basis. After the group test followed a ten-minute individual test in reading (word-decoding). |

|

|

|

|

|

Примерок |

|

Sample |

|

|

|

|

|

Во девет училишта во Грац беа испитувани 187 ученици од петто одделение (123 момчиња и 64 девојчиња). Од нив 95 беа момчиња и 49 девојчиња без ПОП, додека 21 момче и 14 девојчиња имаа ПОП и учеа во инклузивни одделенија. Овие 35 ученици со ПОП претставуваа 39% од вкупниот број на ученици од петто одделение со ПОП во инклузивните одделенија во Грац (24). Просечниот број на ученици во одделенијата беше 23, од кои четири од шест студенти со ПОП беа инклудирани. Двајца ученици со ПОП од инклузивните одделенија не можеа да комуницираат поради тешко нарушување (интелектуална попреченост); овие лица имаа некомплетни резултати. Една девојка и седум момчиња со ПОП посетуваа училиште за посебно образование. Ова е единственото посебно училиште во Грац за ученици со ПОП (покрај училиштето за лица со тешка попреченост). Голем број од учениците (28) беа дијагностицирани со пречки во учењето, двајца ученици имаа Аsperger аутизам и пет ученици беа дијагностицирани со интелектуална попреченост. |

|

187 fifth grade children (123 boys, 64 girls) from nine schools in Graz were investigated. Of these, 95 boys and 49 girls were without SEN, while 21 boys and 14 girls had SEN and studied in integrative classrooms. These 35 SEN students represented 39% of the total number of fifth grade students with SEN in the integrative classrooms in Graz (24). The average number of pupils per class was 23 students, in which four to six students with SEN were integrated. Two students with SEN in the integrative classrooms could not communicate due to severe impairment (intellectual disability); these individuals had incomplete results. One girl and seven boys with SEN attended a special education school. This is the only special school in Graz for SEN students (except the one for students with severe disabilities). The majority of students (28) were diagnosed with a learning disability, two students had Asperger Autism and five students were diagnosed with intellectual disabilities. |

|

|

|

|

|

Инструменти |

|

Instruments |

|

|

|

|

|

Беа користени психометриските тестови CFT20R, ELFE, SLRT II, HSP, ERT & FDI. |

|

The following psychometric tests were used: CFT20R, ELFE, SLRT II, HSP, ERT & FDI. |

|

|

|

|

|

3. Резултати |

|

3. Results |

|

|

|

|

|

Часови во инклузивното образование |

|

Hours in integrative education The numbers of hours in the integrative education are represented according to the curriculum (30, 31). The amount of integrative schooling is given per pupil in school hours. A description in percentage is not useful since the number of school hours per week was various. Furthermore, the number of hours of integrative schooling for students with SEN varied from 15 to 30 hours per week (M = 22.6, SD = 4.5). RC students were schooled M = 25 hours per week in integrative classrooms. The amount of support outside the classroom for RC students was on average one hour per week. Students in the GSS curriculum had an average of M = 22.55 hours per week in integrative settings and M = 4.41 hours per week in segregated settings. Students following the SMH curriculum also had M = 17.5 hours in integrative settings and M = 4.5 hours per week in segregated settings. On average, one integration teacher allocated M = 22.5 (SD = 0.52) hours per week in an integrative classroom. |

|

|

|

|

|

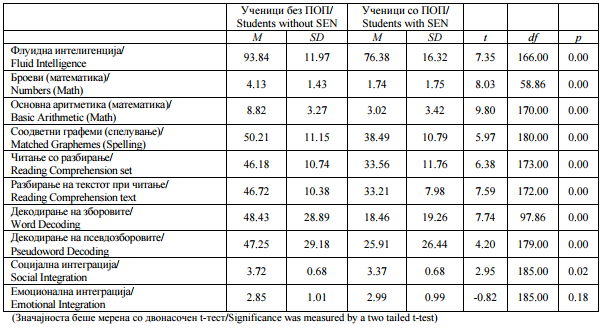

Успех и социјална инклузија на учениците со и без ПОП Со цел да се споредат резултатите, просечните резултати од тестирањето се прикажани во табелата 1. Бидејќи вреднувањето на индивидуалните тестови варираше, сите добиени резултати беа претворени во z-резултати, како што е прикажано на слика 1. За таа цел, беа користени нормализирани резултати. Разликата помеѓу учениците со ПОП и без ПОП беше тестирана со помош на двонасочниот t-тест. |

|

Performance and social integration of students with and without SEN In order to compare the results, averages of the scales were shown in Table 1. Since the scaling of the individual tests varied widely, all raw test scores were transformed into z-scores, as shown in Figure 1. For this purpose, the normalized scores were used. The difference between the students with SEN and without SEN was tested using the two tailed t-test. |

.jpg)

|

Слика 1: Средна вредност од индивидуалните тестирања на учениците трансформирана во z скала |

|

Figure 1: Means of individual tests of the students transformed into z-scale |

|

|

|

|

|

Кога станува збор за флуидната интелигенција и успехот на училиште, учениците без ПОП постигнаа редовни резултати, за разлика од оние со ПОП кои беа рангирани едно стандардно отстапување пониско. |

|

In terms of fluid intelligence and school performance, the students without SEN achieved regular scores whereas those with SEN were positioned one standard deviation below. |

|

|

|

|

|

Табела 1: Средно и стандардно отстапување кај учениците во резултатите од тестирањето и прашалниците |

|

Table 1: Mean and standard deviation of the students’ results from the tests and questionnaires |

|

На двете математички скали, учениците без ПОП постигнаа значително повисок резултат споредено со учениците со ПОП. Разлика слична со резултатите со основната аритметика беше пронајдена помеѓу учениците без ПОП и со ПОП во читањето, спелувањето и декодирањето на зборови. Додека тестовите за читање и спелување беа вреднувани преку t-тестот со средна вредност од 50 и стандардна девијација од 10, тестот за декодирање на зборовите користеше проценти за рангирање. |

|

On both mathematical scales, the students without SEN achieved a significant higher score than the students with SEN. In reading, spelling and word-decoding a difference similar to the results in basic arithmetic was found between students without SEN and with SEN. While the reading and spelling tests were measured in t-Scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, the word-decoding test used ranking in percentages. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Дискусија |

|

Discussion |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Според бројот на часовите во инклузивното образование, беше откриено дека учениците кои го следеа РНП и учениците кои го следеа ОПНП најмногу беа образовани во инклузивни одделенија. Спротивно на тоа, учениците со ТПП поминаа помалку време во инклузивните одделенија. Резултатот е сличен на заклучокот на Schiller и сор. (5) и може да се поддржи со фактот дека часовите за учениците со ПОП се договорени помеѓу директорот на училиштето и родителите. Според тоа, учениците со ТПП имаат помалку часови. Овие часови се договорени за секој ученик посебно, а вкупниот број на часови е различно распределен по различни предмети. Разликата помеѓу редовните ученици со ПОП во однос на флуидната интелигенција и академските достигнувања соодветствува со другите истражувања (11, 13). И покрај тоа што според училишниот успех резултатите беа слични на американските лонгитудинални истражувања (7). Ова значи дека по предметот математика, редовните ученици беа способни да преминат на нов предмет во петто одделение, додека учениците со ПОП сè уште имаа големи проблеми со основната аритметика, особено со множењето и делењето. За споредба, петтоодделенците со ПОП постигнаа средна вредност слична на онаа на седмоодделенците од германските посебни образовни училишта (32). Училишниот успех на учениците со ТПП при училишните тестирања беше на најниска можна граница. Понатаму, овие резултати беа постигнати со голема поддршка од страна на тимовите за тестирање. |

|

With regards to the number of hours in integrative schooling, it was discovered that RC and GSS students were schooled the most in integrative classes. On the contrary, SMH students spent less time in integrative classes. This result is similar to Schiller et al. (5) conclusions and can be supported by the fact that lessons for students with SEN are negotiated between the head masters and the parents. Hence, students with SMH have fewer lessons. These lessons are negotiated for each student individually, and the determined total hours are allocated differently in various subjects. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Заклучок |

|

Conclusion |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Во заклучокот, резултатите покажаа дека инклузивните одделенија се карактеризираат со голема хетерогеност. Моментално постојат голем број часови кои поддржуваат индивидуални ученички групи. Значајно е да се спомне дека на инклузивното образование сè уште му недостигаат инклузивни методи на предавање, посебно развиени за учителите. Сè уште недостасуваат заедничка наставна програма, образовни програми и материјали кои би овозможиле профитабилно образование без оглед на разликите во успехот по математика и германски јазик. |

|

In Conclusion, the results show that integrated classes are characterized through a great heterogeneity. Currently, there are plenty of lessons, which support individual student groups. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that inclusive teaching still lacks inclusive teaching methods, specifically developed for team-teaching. Common curricula, learning programs and materials that enable a profitable coeducation are still missing, despite of the differences in the achievement in mathematics and German language. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Citation: Gebhardt M, Schwab S, Krammer M, Gasteiger BK. Achievement and Integration of Students with and without Special Educational Needs (Sen) in The Fifth Grade. J Spec Educ Rehab 2012; 13(3-4):7-19. doi: 10.2478/v10215-011-0022-6 |

||||

|

Article Level Metrics |

||||

|

Референци/References |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

1. European Agency. Grundprinzipien zur Förderung der Qualität in der inklusiven Bildung: Empfehlungen für Bildungs- und Sozialpolitiker/innen; 2009 [cited 2012 Мar]. Available from: URL:http:// www. european-agency. org/ publications /ereports/ key-principles- for- promoting- quality -in- inclusive –education /key -principles- DE.pdf.

8. Myklebust JO. Inclusion or Exclusion?: Transition Among Special Needs Students in Upper Secondary Education in Norway. European Journal of Special Needs Education 2002; 17(3):251–63. |

|

17. Huber C. Soziale Integration in der Schule?: Eine empirische Untersuchung zur sozialen Integration von Schülern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf im Gemeinsamen Unterricht. Marburg: Tectum; 2006.

24. Landesschulrat Steiermark. Statistik der Schülerzahlen. Graz; 2011. |

||

Share Us

Journal metrics

-

SNIP 0.059

SNIP 0.059 -

IPP 0.07

IPP 0.07 -

SJR 0.13

SJR 0.13 -

h5-index 7

h5-index 7 -

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Google-based impact factor: 0.68

Related Articles

10 Most Read Articles

- PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE / REJECTION AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS WITH AND WITHOUT DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

- RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIFE BUILDING SKILLS AND SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT OF STUDENTS WITH HEARING IMPAIRMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR COUNSELING

- EXPERIENCES FROM THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM – NARRATIVES OF PARENTS WITH CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN CROATIA

- INOVATIONS IN THERAPY OF AUTISM

- AUTISM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

- DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDERS – AN OVERVIEW

- THE DURATION AND PHASES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- REHABILITATION OF PERSONS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY

- DISORDERED ATTENTION AS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL COGNITIVE DISFUNCTION

- HYPERACTIVE CHILD`S DISTURBED ATTENTION AS THE MOST COMMON CAUSE FOR LIGHT FORMS OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY